by Joshua Groffman

Abstract

This article seeks an account of how music and sound participate in the socio-cultural mediation of landscape. I adopt perspectives from previous ecomusicological studies, as well as the field of soundscape ecology, for my analysis. Using as a case study the marketing of a multi-million-dollar estate in the Hudson River Valley town of Millbrook, NY, I examine “soundtrack and soundscape”: the music of a “virtual tour” used to market the estate, along with soundscapes recorded in and around the environs of Millbrook.

I theorize the effects of the virtual tour on bodily experience of landscape and discuss the utility of soundscape ecology in an ecomusicological context. Soundscape observation creates an opportunity for emplaced analysis, inquiring into those sounds that are mimicked, recontextualized, or covered up altogether by the music in the video. I discuss an observation protocol based on the practice of soundscape ecologists and describe data and recordings gathered in 2018 at several sites in Millbrook. I consider sonic experience within the context of cognitive landscape hypothesis, a framework for understanding how music and soundscape together shape, and are shaped by, embodied interactions with physical environments. Finally, I return to the video. An integrated discussion of music and sound asks not only how the real estate video’s formal features relate to imagery, advertising, and other cultural artifacts that deal with natural or pastoral topics; it also suggests how engagement with the embodied experience of landscape is a way of disrupting some of the real estate video’s rhetorical logic, which I analyze as an example of discourse that across much of US history has cordoned off large segments of the landscape along barriers of class and race.

Andrew Haight Road, Millbrook, NY. Photographed by the author.

Are we, indeed, welcome at Millbrook

In the great estate houses

Their mouldings crumble, woodpanels scratched

By pencils & hairpins in the hands of the infants of the poor

Are we, indeed, welcome to the fruits of the earth— Diane Di Prima, “Ode to Keats” (1971)

Millbrook, NY, lies some ninety miles north of New York City and fifteen miles east of the Hudson River as it flows past the river city of Poughkeepsie. Ringed by parcels of hundreds of acres of rolling hillside, forest, and farmland, some in family ownership dating from the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries, Millbrook has long been endowed with wealth and natural beauty. A poem from the mid-twentieth century by resident Vincent Sepe exemplifies a long-running tendency to characterize Millbrook as an oasis of pastoral splendor and set it apart from the urban environs of New York City.

Vincent Sepe, Sr., “Millbrook” (mid-20th century)

Nestling ‘mong the hills calm and serene,

Millbrook gives her grace its full display;

Impatient hounds reveal the fox at bay,

While hunters ride through endless fields of green.

Proud and stately mansions dot the scene,

And Bennett School enacts the classic play;

Here nature ruled that Beauty hold full sway,

Placing on her head the crown of queen.

O, Beauty lovers, pause and feast your eyes,

For here God placed a bit of paradise.Courtesy of the Millbrook Historical Society

Recently, Millbrook has been part of a broader shift in the Hudson River Valley that has served weekenders and second home-buyers seeking a “real city break” (Lonely Planet 2012) and an alternative to Long Island’s Hamptons (HudsonValley360 2018). Rhetoric surrounding the village continues to emphasize its natural beauty, often with reference to the cultural tropes of English foxhunting; an article on Millbrook’s horse- and hunt-related amenities dubs it “America’s Cotswolds,” and further notes that listing an address as “in Millbrook” is said to justify the addition of a zero to its sale price (Rosendale and Baldridge 2015, 49). The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 further heightened real estate pressure; during the spring and summer of that year there was a notable influx of residents to the Hudson Valley, and housing stock changed hands at a brisk pace (Simons 2020; Haag 2020; Tallaferro 2021).

Lightning Tree Farm, a 600-acre estate four miles from the center of the village, was placed on the market in 2016 for an original asking price of $28.5 million. On the website for the property, lightningtreefarmestate.com, the “About” page states: “Lightning Tree Farm reigns as the dominant property in the midst of Millbrook hunt country. A property of sophistication and grandeur, it is more than a home…it is a lifestyle statement.”

Video 1. YouTube video of virtual real estate tour of Lighting Tree Farm, Millbrook, NY, produced by 929 Media.

That such money is at stake accounts, surely, for the high production values of the “virtual tour” created to market the property online (video 1). The video’s lavish visuals of the estate, house, and outbuildings are shot from the perspective of a potential buyer, who explores the grounds from behind the camera’s eye. The video presents a carefully-staged experience that joins indoor and outdoor environments at several levels of scale. With shots of open doors, open windows, and curtains billowing in the breeze, the interior spaces of the house are made seamless with the immediate landscape of grounds and private amenities. The opening image of a car driving into the estate and the closing shot of a helicopter departing it weds Lighting Tree Farm, in turn, to the wider landscape of the Hudson Valley and its proximity to New York City. These shots simultaneously reinforce the estate’s pastoral isolation while emphasizing access to urban conveniences. The video thus emphatically links the beauty of the landscape—the estate’s picturesque house and private terrain, surrounded by similarly large and attractive parcels—to a pattern of access enabled by large sums of money. The natural world, occasionally valorized in the U.S. as a common resource or good (Hays and Hays 1987; Cannavò 2001), is here made exclusive. The virtual tour proposes a slew of exegetic questions concerning place, the natural world, and the politics of inequality.

This article proposes that these questions might be productively explored through an ecocritical analysis rooted in music and sound. Although the visuals are eye-catching and enticing, it is the video’s music that does the real affective and narrative work of immersing us in the experience of Lightning Tree Farm, transforming a collage of imagery into a powerful presentation laden with valences of sublimity. Furthermore, as the music narrativizes our introduction to Lightning Tree Farm it also replaces (and re-places) the soundscape of the property. One question raised by the video, then, concerns the rhetorical gesture of swapping soundscape for soundtrack and what it might reveal about the video’s ideological commitments.

This article continues previous work I have done on the entanglements of environment, sound, and music in the Hudson Valley. In a previous paper (Groffman 2019), I traced the sounding lineage of Hudson Valley “pastoral ideology” (Buell 1995, 32–33) as a “real city break” during the long nineteenth century. Soundscape has often been made central to a characterization of the Hudson Valley as a landscape of sublime silence and quiet, a not-city space distinct from New York City. Silence and quiet were also used to characterize the indigenous people who inhabited the Valley; by marking them as sonically non-present, pastoral ideology was made part of the ongoing project to hear the landscape as an “empty” site for European colonization and habitation. Such soundings of the Hudson Valley emerge in musical pieces and are also heard through the characterization of sound and music in poetry, prose, and landscape paintings that take the Valley landscape as their subject.

My discussion of the virtual tour assays a similar analysis within the contemporary context of Millbrook, highlighting the extent to which media can create a highly stylized and specific experience of a landscape that is densely-storied and richly textured with overlapping communities. The hunt-centric lifestyle on offer at Lightning Tree Farm unfolds a few miles from my childhood home; yet it differs from what I encountered as a comfortably middle-class kid attending the public high school (and benefiting, despite my unawareness, from the school taxes paid by Millbrook’s estate owners). It differs further still from the experience found on the small, conventional dairy farm in Millbrook run by my in-laws. A complete account of Millbrook’s soundscapes attentive to the politics and rhetoric of environmental perception and values would listen to those working-class farms that historically dominated the landscape as well as: the overlapping stories of the newer operations that have popped up to service the farm-to-table movement; the Munsee and Mahican communities that lived along the banks of the Hudson prior to, and throughout, the colonial incursion of Euro-Americans; the Quaker community that built South Millbrook in the 1700s; the Irish and Italian immigrants who came to build Millbrook’s estates in the 1800s; even, perhaps, the echoes of the Merry Pranksters’ visit with Timothy Leary at his Millbrook residence in 1964 (Benham 2005; Ghee and Spence 2000; Di Arpino 1988; Tompkins 2002).

Previous studies (Rehding 2011; Allen, Titon, and Von Glahn 2014) have established ecomusicological analysis as necessarily political. This is to say that such analysis is inextricable from the socio-cultural milieu of the analyst. But it further suggests, as Mark Pedelty (2012, 11) writes, that musical aesthetics and meaning must be considered as emerging from “material contexts and effects”: that ecocritical methods should be attentive to the intermingled formal properties of cultural objects and the impact of those properties on socio-cultural politics. My own analysis will argue that the real estate video is a specific instantiation of the discourse that across much of U.S. history has cordoned off large chunks of the landscape along barriers of class and race (Anguelovski et al. 2018; Finney 2014; Park and Pellow 2011). This discourse is both mirror and agent: it relies on a recognition of the Hudson Valley as a pastoral space, laden with natural beauty, while in turn molding and shaping perceptions of that beauty. Previous ecomusicology scholarship suggests points of departure for analyzing how music of place and environment interacts with the formal conventions of Euro-American classical music (Allen 2011; Saylor 2008; Philpott, Leane, and Quin 2020; Taylor 2016; Von Glahn 2016) and popular music (Størvold 2019; Guy 2009; Mitchell 2009; Ingram 2010) to depict natural contexts. I am particularly interested throughout in the linkages between musical rhetoric and “the affective qualities of particular landscapes” (Grimley 2011, 395) and what these can tell us about pastoral ideology as they relate to personal, regional, and national identity formation processes (Grimley 2006; Guy 2019; Hogg 2015; Von Glahn 2003).

Finally, ecomusicology’s original formulation—“music, nature, and culture in all the complexities of those terms” (Allen 2014, emphasis mine)—along with accompanying discussion (Cooley et al. 2020; Titon 2013; Ochoa Gautier 2016) have made it clear that the field’s inquiry should extend beyond readings of musical texts into sound, broadly construed. This article continues work (Post and Pijanowski 2018; Guyette and Post 2016; Groffman 2019) that has incorporated concepts and methodologies from the field of soundscape ecology, a branch of landscape ecology that investigates soundscape composition, diversity, intensity, and patterns within the context of human and non-human activities (Pijanowski, 2011).

My discussion unfolds in four parts. I describe the music of the real estate video and how it is used to narrativize the video’s imagery. Describing the effects of the video on bodily experience of landscape leads, secondly, to a discussion of the utility of incorporating soundscape ecology in an ecomusicological context: it creates an avenue for emplaced analysis, re-configuring the aural component of the video by inquiring into those sounds the music is replacing. I discuss a soundscape observation protocol based in soundscape ecology (Matsinos et al. 2008) and describe data and soundscape recordings gathered at Lightning Tree Farm, as well as two other comparison sites in Millbrook: my in-laws’ dairy farm and the main street of the village. Third, I consider sonic experience within the context of cognitive landscape hypothesis (Farina and Belgrano 2006), a framework for understanding how music and soundscape together shape, and are shaped by, embodied interactions with physical environments.

Finally, I return to the video. Through an integrated hearing of music and sound, soundtrack and soundscape, I hope to make explicit what I have previously called “the circular relationship between the soundscape of physical place and the manifestations of culture which hear, interpret, and value that place” (Groffman 2019, 3). Together, music and sound studies can ask not only how music’s formal features relate to imagery, advertising, and other cultural artifacts that deal with natural or pastoral topics; they also suggest how engagement with the embodied experience of Lightning Tree Farm is a way of disrupting some of the real estate video’s rhetorical logic. What sounds are present in the physical landscape of Millbrook? How does the video’s music relate to these sounds by mimicking them, re-contextualizing them for the listener, or covering them up altogether? How does the music change the viewer’s relationship to Lightning Tree Farm and Millbrook? Such questions underpin the larger one posed by Nancy Guy (2009, 220): “In what ways have musical creativity itself affected humankind’s relationship to the natural world?”

The Music of Lightning Tree Farm

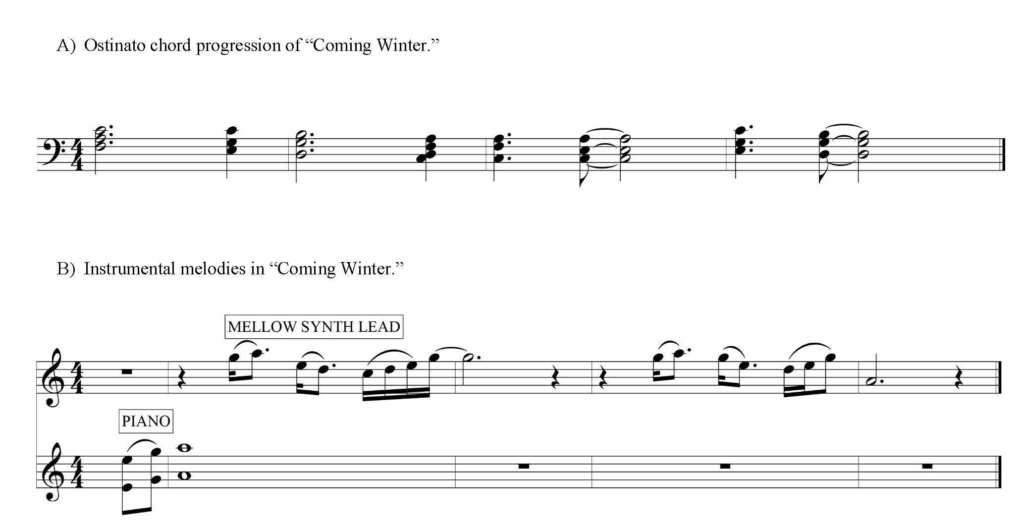

The virtual tour is soundtracked by “Coming Winter” (2015), a pre-existing song by the Australian musician Generdyn licensed for use in the video by the production company 929 Media. The track uses blended conventions of Euro-American classical and pop music in a style identified as “dramatic,” “serious,” and “uplifting” in the song’s metadata on the licensing site musicbed.com. It features a mixture of instruments that lend their connotations of history and cultural prestige, particularly solo and ensemble string sounds and piano, all crossed with the contemporary timbres of programmed drums, electric guitar, and a spinning synth lead. The track deploys a loose pandiatonicism lying in the lightly melancholic terrain between C major and A minor to achieve its “serious” and “uplifting” affect. A cycling, four measure progression heard throughout implies a resolution, never achieved, to C major (example 1A), while synth and piano melodies and drones repeatedly invoke A as a quasi-tonic (example 1B).

Example 1A. Ostinato chord progression of “Coming Winter.”

Example 1B. Instrumental melodies in “Coming Winter.”

The version of “Coming Winter” heard in the virtual tour is one of multiple: in another, tagged with the label Epic Vocal Pop on YouTube, the instrumental track is overlaid with a male voice and the image of “coming winter” is made a metaphor for overcoming adversity: “I was alone / I was betting on my last hope / I can win I can win I can win this time / Coming winter, I’ll be / Everything you need, everything you need.” Set to a slow, chugging rhythmic groove, bathed in reverb, “Coming Winter” accumulates ever denser textures and more active rhythms; suspended cymbal rolls and a beat drop at m. 27 complete a narrative of brooding portent growing to transcendent climax.

Example 1C: Transcription of “Coming Winter” by Generdyn, as used in virtual tour of Lightning Tree Farm.

“Coming Winter” is aptly chosen as soundtrack for a piece of audio-visual advertising centered around place. Voyles (2021, 129-131) shows how place-based advertising can participate in a process of meaning-making within landscape. In her analysis of the marketing of California’s Salton Sea, she documents how advertising can take the facts and features of the human and physical environment and portray them for ideological purposes, suppressing or erasing altogether the presence of some communities (in her study, the indigenous Cahuilla clans who historically inhabited the area), while suggesting the appropriate presence of others (white vacationers seeking new tourist destinations). In a similar way, “Coming Winter” maps onto Grimley’s (2018, 28) observation that any musical depiction of place is “unavoidably political: shaped by, and giving sounding form to, the complex socio-cultural environments in which it was produced and performed.” To a certain extent, the music reflects the realities of Millbrook: the classically-tinged instrumentation, with its implications of white Euro-American history and prestige culture, are a sonic stand-in for a landscape in which racial minorities and working-class populations are largely absent (figure 1) because of structural factors such as housing prices (Brandon 2020).

| United States | New York State | Dutchess County | Village of Millbrook | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 318,558,162 | 19,697,457 | 295,905 | 1,491 |

| % White | 73.3 | 64.3 | 78.8 | 90.4 |

| % Hispanic/Latino | 17.3 | 18.6 | 11.5 | 6.8 |

| % Black/African American | 12.6 | 15.6 | 10.4 | 0.6 |

| Mean Income ($) | 77,866 | 89,397 | 93,356 | 108,256 |

| Median Income ($) | 55,322 | 60,741 | 72,706 | 75,150 |

Source: US Census Bureau, 2012–2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates

Figure 1. Demographic and income data for Millbrook, NY.

Still, many of the communities presently inhabiting Millbrook will find at most a passing resemblance to their lives within the video. Instead, the depiction of Millbrook that emerges relies on a set of techniques similar to those documented by Stimeling (2014) in his study of Gulf Coast tourism advertising: a musical style that invokes historical tropes to provide an apolitical sheen to the proceedings and an essentializing stance that glosses over hybrid situations, such as increasing suburban-style development around the rurality of Lightning Tree Farm. The combination of detailed, site-specific imagery and heroic music results in a highly stylized portrait of the Millbrook landscape that presents an appearance of verisimilitude in its depiction of place.

Further effects are achieved through the immersive quality of audio-visual presentation, which prompts an embodied reaction to dramatic and uplifting music experienced in tandem with sumptuous visuals. Like the experience of landscape, the experience of media is intersensorial and multimodal (Hogg 2015, 283-284): the co-constitutive effects of sounds and sights invoke a wide range of reactions drawing in memory, emotion, and other sensory stimuli. The real estate tour is not merely “showing” the viewer the place but tells her, in essence, how to feel about it. The narrative of overcoming adversity found in “Coming Winter” transfers neatly to a real estate transaction. The viewer is made to feel that something is at stake in this presentation of landscape: a chance to make a lifestyle statement, to be everything you need. Benedict Taylor (2016, 220) argues that place-based imagery and music move beyond the “purely mimetic,” instead “capturing dynamic and sensory qualities as conveyed to a subject…not narrative so much as symbolic of the ecology between man and nature.” His analysis of Mendelssohn’s Hebrides overture shows that the effect media has for the listening/viewing subject is a fundamentally embodied one, invoking all the senses in an experience that “encapsulates a wealth of dynamic, sensory, and subjective responses to place, time, myth, history, and memory” (214). Proffered as a simple “tour,” the video in fact proposes an encompassing formulation of the qualities of natural beauty within the Millbrook landscape and the desirability that the viewer purchase and inhabit a sizeable piece of it.

Yet, if it is true that visual and sonic media can invoke and mold embodied experience of landscape, this also raises two contradictions implicit within the video. These suggest the next steps in this discussion. The first concerns the idea that a “tour” implies a promise of emplacement, the “sensuous interrelationship of body-mind-environment” (Howes 2005, 7). It hardly seems promising to seek emplacement via a YouTube video that is accessible anywhere there is internet access and a soundtrack comprised entirely of sampled and synthesized (i.e., disembodied) sounds. On the other hand, body, mind, and environment are all relevant to the experience of the video, alternately activated, stimulated, and influenced. It is thus fairer to say that the body-mind-environment interrelationship is fundamentally reconfigured by virtue of its mediatized status in the video—Lighting Tree Farm is not so much de-placed as re-placed. It is this process of re-placing, of staging place in service of environmental and economic politics, that this study is seeking to pin down.

This raises a further re-placing in which the music, especially, is complicit: that of the absent soundscape. Although the real estate tour is by no means unique in this regard, it is worth pausing over the fact that while the visuals are sourced with great specificity from Lightning Tree Farm, the soundscape of the place is heard nowhere in the video. Instead, body, mind, and environment are reconfigured still further, visuals repackaged with different sounds that mesh highly localized sights with an aural experience deploying the universalizing tropes of Euro-American culture.

This suggests that it is to soundscape that we might turn next, towards a discussion of the aural qualities of the landscape considered alongside the musicalization of that landscape enacted by “Coming Winter.” The considerations raised in the above discussion—video as a stylized and essentially political portrait of Millbrook; music as a vehicle for symbolizing an experience of human subjectivity within landscape; bodily experience and soundscape as re-placed by the music—suggest that an analytical response rooted in music and sound together may make explicit the affective logics driving the video’s cultural and environmental politics.

Soundscape Ecology in the Context of Ecomusicology

Encountering the soundscape of Lightning Tree Farm as part of an analysis of the video offers particular tools for contesting the ad discourse, premised on an intentional, sensuous immersion in the landscape. Practitioners in the field of acoustic ecology have positioned an attentive listening to soundscape as an antidote to a constant influx of media and sensory stimuli resulting in “information poisoning” (Stocker 2013, 2; see also Westerkamp 2019). Stocker (24-25) lays emphasis on how the auditory experience of media—music, sound effects, and dialogue—is carefully crafted to command the listener’s attention with maximum force and contrasts this with the more entropic, less calculated experience of the auditory environments around us in daily life.

The opposition between the craftedness of music and the “naturalness” of soundscape can be easily overstated; I hold that, in fact, soundscape is a highly ideological document that reflects the “politics of everyday life” (Doughty, Duffy, and Harada 2019, 1) and the histories and identities of those that construct them quite as much as music does. However, it is true that most soundscapes lack the immediacy and affective punch that music can command; it is for this reason that “Coming Winter” is an effective substitute for the soundscape of Lightning Tree Farm in the marketing video. Analyzing soundscape invites a repeated going-into, a purposeful emplacement that resonates with the methods of more-than-representational research: “multifarious, open encounters in the realm of practice” (Lorimer 2005, 84). Thus it is that scholars interested in the cultural geography of music suggest a pivot away from (solely) considering formalist musical texts and towards music’s capacity to control and “reconfigure” physical space and time (Doughty, Duffy, and Harada 2019, 3). Without romanticizing the idea of “listening to nature,” I believe the insights soundscape study offers can serve as an alternative way of hearing Millbrook that differs from the landscape that sounds in the video. Such a response might confront the socio-cultural rhetoric presented by pulling apart its components, making explicit by comparison the structures it is invoking and reinscribing.

The branch of landscape ecology known as soundscape ecology offers, in particular, a comprehensive approach for listening-in-place as part of the analytical endeavor. Originating in the mid-2000s (Pijanowski et al. 2011; Farina 2014), its aims include evaluations of diversity and ecosystem health through sound, preserving remote and wild soundscapes, and understanding and mitigating the impacts of anthropogenic sound on animal behavior and health. Although soundscape ecology is oriented towards an audience and a body of questions that is distinct from more humanities-oriented ecocritical studies, its approach to sound can overlap productively with the careful consideration of sound’s aesthetic, formal, and cultural properties that grounds acoustic ecology, sound studies, and musical analysis; indeed, Pijanowski et al. (2011, 204) note the influence on their work by practitioners at home in the humanities, particularly the work of R. Murray Schafer (1993) and Barry Truax (1999), who were generative in their commitment to noticing and describing analytically sounds within the landscape (see also Järviluoma et al. 2009; Droumeva and Randolph 2019).

At the same time, soundscape ecology’s methods provide a useful supplement to pre-existing procedures in acoustic ecology, particularly if we are seeking an explanation of how cultural artifacts may be influencing our hearing of the soundscape. By de-centering anthropocentric perspectives for a “larger socioecological systems approach” (Pijanowski et al. 2011, 204) and incorporating insight from bioacoustics and biosemiotics, soundscape ecology provides a means of theorizing the contingent nature of perception within landscape. It can thus enlarge, nuance, and even challenge insights that emerge from documentary artifacts and ethnographic perspectives—such as soundwalking, sound surveys, or interviews—that reflect personal listening habits, histories, and socio-cultural politics.

In this study, I employed a 10-minute soundscape protocol described by Matsinos et al. (2008, 948–949). The protocol employs a single taxonomy, that of biophony, geophony, and anthrophony (B/G/A) (Krause 1987; Pijanowski et al. 2011, 204) to organize analysis. The B/G/A taxonomy provides a useful means of categorizing sounds within the landscape that acknowledges human alteration to the soundscape while directing attention to its many non-human features. Biophony describes sounds made by living organisms; geophony is sounds created by non-living natural phenomena such as rain, wind, and running water; and anthrophony is sounds created by “human activity and artefacts (i.e., transportation, constructions, agricultural and housekeeping activities)” (Matsinos et al. 2008, 948).

The Matsinos et al. protocol calls for evaluation of the relative intensities of B/G/A at fifteen second intervals on a 0-3 scale, with 0 equivalent to “no intensity,” 1 to “low intensity,” 2 to “medium intensity,” and 3 to “high intensity.” To counter the somewhat subjective nature of these rankings, I oriented my hearing around the guideline that any one of the B/G/A parameters that began to “mask” (Truax 1999) the other two merited an intensity ranking of 2. I also used a Mererk Digital Sound Level Meter to record the ambient noise level of the soundscape at one-minute intervals.

| Location* | Date | Observation Start Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Franklin Avenue | 19 May 2018 | 5:55 a.m. | Recording |

| Andrew Haight Road | 19 May 2018 | 6:20 a.m | Recording |

| Franklin Avenue | 19 May 2018 | 11:00 a.m. | Recording |

| Franklin Avenue | 19 May 2018 | 8:50 p.m. | Recording |

| Uplands Farm | 21 May 2018 | 6:32 a.m. | Recording |

| Uplands Farm | 21 May 2018 | 11:04 a.m. | Recording |

| Uplands Farm | 21 May 2018 | 3:55 p.m. | Recording |

| Uplands Farm | 21 May 2018 | 8:57 p.m. | Recording |

| Andrew Haight Road | 24 May 2018 | 3:55 p.m. | Recording |

| Andrew Haight Road | 25 May 2018 | 10:59 a.m. | Recording |

| Andrew Haight Road | 5 July 2018 | 11:00 a.m. | Recording |

| Uplands Farm | 5 July 2018 | 4:00 p.m. | Recording |

| Andrew Haight Road | 6 July 2018 | 6:00 a.m. | Recording |

| Andrew Haight Road | 6 July 2018 | 4:00 p.m. | Recording |

| Andrew Haight Road | 6 July 2018 | 9:00 p.m. | Recording |

| Franklin Avenue | 7 July 2018 | 6:00 a.m. | Recording |

| Franklin Avenue | 7 July 2018 | 11:00 a.m. | Recording |

| Franklin Avenue | 7 July 2018 | 4:00 p.m. | Recording |

| Franklin Avenue | 7 July 2018 | 9:00 p.m. | Recording |

| Uplands Farm | 8 July 2018 | 6:00 a.m. | Recording |

| Uplands Farm | 8 July 2018 | 11:00 a.m. | Recording |

| Uplands Farm | 8 July 2018 | 9:00 p.m. | Recording |

* Scheduled soundscape observations on Franklin Avenue at 4:00 p.m. on 19 May 18 and Andrew Haight Road at 9:00 p.m. on 21 May 2018 were not conducted due to logistical issues.

Example 2. Schedule and recordings of soundscape observations done in Millbrook, NY, May and July 2018.

Ten-minute soundscape observations were conducted at three sites on the dates and times detailed in example 2. Of these sites, most relevant to this study is Andrew Haight Road, a dirt lane chosen for its proximity to Lightning Tree Farm’s 600 acres. The other two sites are on Franklin Avenue, the main thoroughfare of the village of Millbrook, and outside the milking parlor of Uplands Farm, run by the Van Tassells for four generations and typifying the tradition of small, family-run farms in the Hudson Valley. I have collected soundscape data at these three sites since 2016; data from Franklin Avenue and Uplands Farm are invoked here largely as points of comparison with Andrew Haight Road but merit stand-alone discussion at a later date.

Matsinos et al. conducted observations throughout the day to capture the ebb and flow of sound patterns. I chose to do observations at each of four timepoints: 6:00 a.m., 11:00 a.m., 4:00 p.m., and 9:00 p.m. I conducted observations at the three sites and four timepoints in May and July to examine seasonal variations in soundscape, with a total goal of twenty-four observations (three sites x four timepoints x two seasons).

Figure 2. Data collection sheet used for soundscape observation, based on Matsinos et al (2008).

The observation protocol, completed with the data sheet shown in figure 2, gives an overview of the sound environment of a site, as well as the interactions of its component sound categories. Combined with field notes taken during the observation, it serves as a record of what was heard during the ten-minute window. And it allows for broad comparisons to be made in spatial and temporal dimensions: between sites and over a period of time at the same site (Krause, Gage, and Joo 2011).

Figure 3. Catalog of sounds recorded at 11:00 a.m. at three sites in Millbrook, NY, July 5-8, 2018.

Each ten-minute observation period was recorded using binaural Roland CS10-EM In-Ear Monitors and a Tascam DR-05 portable recorder, producing the recordings found in example 2. Post-observation examination of a subset of the soundscape recordings was done with Raven Pro, a program for the visualization and analysis of soundscapes. This resulted in the sound catalogs found in figure 3, which identify and analyze the characteristics of individual sound objects within the soundscape of the July 11:00 a.m. observations at the three sites.

Cognitive Landscape Hypothesis: Environmental Perception and Environmental Values

In juxtaposing the data from soundscape observation and the music of “Coming Winter,” I argue that an ecocritical analysis of music and sound in landscape should account for how it is perceived and how it is valued. I proceed from the assumption that what I hear (perception) and how I hear it (valuation) are both mediated by social, cultural, and political processes. Addressing what I hear acknowledges a crucial fact of hearing: not all sounds that come in at the ear of an observer are perceived equally, if they are perceived at all. Instead, my ears gravitate to some sounds while ignoring others. My experience of (sonic) emplacement—the sensuous interaction of body, mind, and environment—emerges as I perceive and evaluate the sounds of the landscape around me. My experience evolves as I remember sounds from other times and places, imagine sounds, add my own, modify those of others.

I further consider that my analysis must make explicit the circular and interdependent construction of my perception and valuation, each acting on the other. Cultural artifacts—music among them, but encompassing, too, soundings of the landscape in poetry, prose, films, and other media—shape the way that soundscape is perceived by an observer, directing attention and channeling affective encounters with these sounds in myriad ways. Depending on where, when, and by whom the virtual real estate tour is experienced, and in what relation to an experience of the physical landscape it represents, it will act in different ways on the viewer’s sensate, imagined, and recalled experience of the place, Lightning Tree Farm.

That an artistic depiction of place, as exemplified by the real estate video, is laden with various forms of ideology that participate in the cyclical process of creating “the environment” as both a category of thought and a physical shaping of the world (in ways ranging from deforestation and construction to climate change) is well established (Grimley 2011, 398). But it bears repeating that the soundscape is an ideological document, too, reflecting our sonic and epistemological predilections quite as much as music does (Chatterjee and High 2017; Coates 2005; Corbin 1998, 2018; Moore 2003; Sterne 2012). Hogg (2015, 289) links the dual experience of landscape and music of landscape through the concept of Henri Lefebvre’s “representational space.” He argues that “landscape, both in its physical actuality and in its musical articulation” is inhabited with signs, markers that are placed there or interpreted as part of a web of representation and ideology. Many aspects of Millbrook’s soundscapes—the whirr of an insect buzzing past an ear, the wind in the trees, the crunch of a luxury automobile’s wheels on a dirt road—will activate feelings, memories, and response in the listener (Rutherford 2017, 48–49). Human alterations to nature frequently engineer the soundscape to produce specific affective experiences, silencing aspects found unsettling and amplifying noises deemed comforting or pleasant.

Put another way, emplacement emerges at the porous interface between my exterior environment (the world “around” me) and interior environment (my embodied, cognitive-affective subjectivity). Emplaced analysis seeks to illuminate the two-way currents between music and sound and between the interior and exterior environments of the embodied, emplaced listener: it interrogates what sound objects are physically present in the landscape, what their histories are, what values and properties are ascribed to them by what actors, and how music and other performative utterances may be changing the way sounds of landscape are perceived and valued.

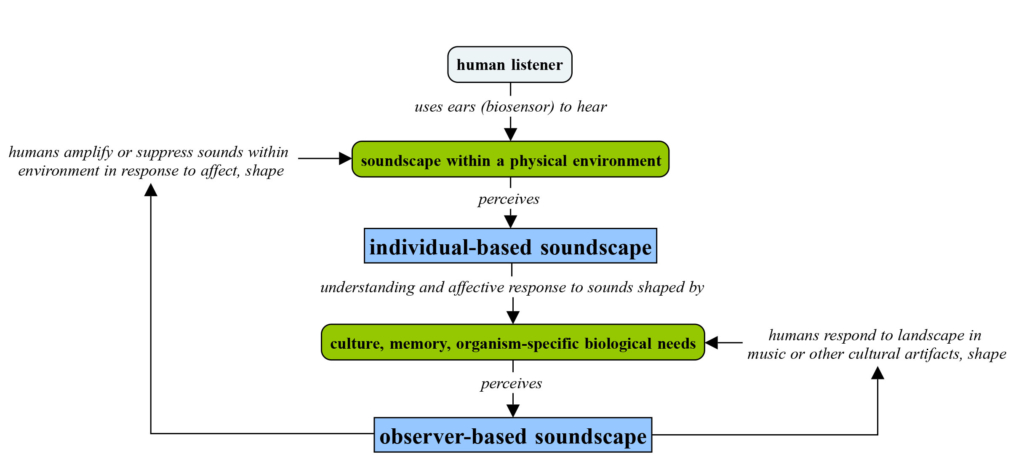

Farina and Belgrano’s (2006) cognitive landscape hypothesis (CLH) provides a useful framework for how we might examine these two-way currents. Farina and Belgrano (2006, 8-9) propose a tripartite understanding of an organism’s perception of, and changing relationship to, the landscape, expressed as the neutrality-based landscape (NbL), individual-based landscape (IbL), and observer-based landscape (ObL).

| Aspect of cognitive landscape | Landscape perceived… | Organism’s cognitive process |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrality-based landscape (NbL) | [landscape not perceived] | Organism inhabits a landscape of “compressed information,” in which “a plurality of mechanisms [create] the conditions for an information world in which structures and energy are abundant and distributed in a stochastic fashion” (2006, 8). However, no meaning is extracted: “intrinsic information of the medium [i.e., landscape] is not perceived by recipients which have no sensors able to capture it” (2014, 5). |

| Individual-based landscape (IbL) | …via bio-sensors (ears, eyes, smell, touch), which extract information from the landscape. | “De-compressed” information is extracted by bio-sensors; results arrive from “sensorial reaction to an external stimulus” (2014, 5); information is data and patterns that could be meaningful but have not yet been made so. |

| Observer-based landscape (ObL) | ….as a modification of the inner environment of the organism as it incorporates new information about the landscape. | Organism assigns a meaning to external signals and environment; information is extracted; a “perceived” landscape is created via trial-and-error learning, social cues, and cultural layouts. |

Figure 4. Cognitive landscape hypothesis (Farina and Belgrano, 2006; Farina and Pieretti, 2014).

In further describing CLH, Farina and Pieretti (2014, 4) adopt a definition of landscape as a “semiotic interface between organisms and their surroundings,” a source of information for organisms to get what they need to survive. They link physiology and cognition through the concept of the cognitive template, which may arise from instinct or cultural learning and which is activated in response to an unmet need. The cognitive template is overlaid on the landscape as an eco-field, “a spatial arrangement inside the landscape, which functions like a carrier of meaning for a specific resource” (5) and which drives the gathering of information for the organism. Organisms use biosensors to receive information from the IbL, gathering data from visual cues, smell, sounds, temperature, and morphology. As these data are made meaningful as patterns, the organism perceives the ObL in order to search the landscape according to a cognitive template, for tangible matter such as food or features that meet physical and socio-emotional needs (shelter, sacred sites). CLH considers the total embodied experience of place on the level of the individual and of the group. Farina and Pieretti (2014, 4) hypothesize the existence of a “private” landscape (a single, individual perspective) and a “public” landscape, which arises from “culturally-fixed, shared characteristics of a (local) aggregation of individuals.”

Constructing the ObL allows an organism to modify the “inner environment” to better adapt to new information or a changing landscape. The pathways between NbL, IbL, and ObL illustrate the interconnected and contingent linkages between the internal environment and the external, biophysical world. In sounding terms, CLH moves from “the way the world sounds” (IbL) to “the way the world sounds to me” (ObL), crossing divides between mind and body, human and non-human.

Figure 5. Human perception and alteration of IbL and ObL.

Soundscape observation protocols of the type I have used in gathering my data in and around Millbrook are specifically indicated (Papadimitriou et al. 2009) as appropriate for an investigation of cognitive landscape. Figure 5 shows how I propose the incorporation of data from these observations into an analysis of cognitive landscape and, particularly, the relationship between soundscape and music, as well as interior and exterior environments. Soundscape observation provides a methodology for tracking facets of the IbL by observing and cataloging those sounds present in the environment as potential data and patterns. These sounds are duly made meaningful by human and non-human observers and constructed as ObL. Emplaced experience of environment emerges as an observer navigates affective encounters with ObL in geographical places and in virtual-cultural spaces like YouTube: overlaid upon landscape imagery, “Coming Winter” refracts physical place through the prism of its formal properties, nuancing and shaping the viewer’s perception of ObL. In reaction to perception of the ObL, humans act within the landscape—buying a house, planting or removing trees, eliminating species intentionally or inadvertently, building roads and more houses—and the soundscape changes accordingly. Both soundscape and soundtrack reflect the ideology that made them; to listen to them in dialogue with one another is to appreciate the circular nature of the perception and valuing of sounds heard and shaped within an environment.

Between Soundtrack and Soundscape

This article has argued that the virtual real estate tour of Lightning Tree Farm raises a number of questions about the entanglements of landscape, music, and the ideologies which shape human relations to the natural world. In considering the role of “Coming Winter” within the video, I have developed the position that to better understand the soundtrack’s manipulation of embodied experience of a particular place—a multi-million dollar estate near the village of Millbrook—“Coming Winter” and the soundscape which it re-places in the video should be considered in tandem, as mutually constitutive experiences. Describing a protocol for soundscape observation based in the methods of soundscape ecology, I have argued that data from these observations can be used to uncover some of the rhetorical and political logics underlying the expressive choices made in the video. In the concluding discussion below, I discuss these data to contextualize and analyze the video’s music in ways that complement a reading of the video’s formal properties. My analysis is bound together by the concept of the cognitive landscape, which theorizes how organisms navigate the process of perceiving sounds in their exterior environments (the individual-based landscape) and transform those sounds into meaningful data and patterns (the observer-based landscape). Cognitive templates create a basis for action by providing internal schemata that are deployed in response to needs and that drive the search within the environment for an eco-field that aligns with the perceived need dictated by the cognitive template.

As ecomusicological investigations have made plain, music is capable of both presenting the landscape and commenting upon it. This is particularly true in the case of a soundtrack to visual media: as Philpott, Leane, and Quin (2020) illustrate in their discussion of Vaughan Williams’s film music, one of the crucial roles of soundtrack in a production in which place and landscape are of central narrative import is to portray both the physical features of the landscape (exterior), as well as to suggest an emotional response to that landscape (interior). Phrased in the language of cognitive landscape hypothesis, we can say “Coming Winter” is impinging on observer-based landscape by creating an experience of the exterior environment (Lighting Tree Farm) and modifying the viewer’s interior environment to make that environment seem desirable. Real estate advertising generally can be understood to be intentionally modifying our internal cognitive templates, seeking to shape a “perceived need” for a very specific resource within the landscape: the advertised home is proffered as an eco-field, “a spatial arrangement inside the landscape, which functions like a carrier of meaning for a specific resource” (Farina and Pieretti 2014, 5).

In my discussion below, I focus on three particular ways in which soundtrack can be heard to be interacting with, and shaping hearing of, the ObL: in its characterization of the landscape of Lightning Tree Farm as that of a sublime and immutable nature, inhabited by a lone human subjectivity imbued with personal heroism; in the way that the music maps on to, and reinforces, long-standing hearings of the relationship between anthrophony and biophony within Euro-American culture; and the extent to which the music participates in a process of contextualizing Lighting Tree Farm as a vintage, antiquarian space that obscures contradictions implicit in the property’s features and the way it is marketed.

Lightning Tree Farm as Sublime Landscape

The video’s opening image of a solitary car travelling into the property emphasizes its pastoral semi-isolation, accompanied by a rich timbral pad. Both the visuals and the music’s reverb-laden lushness create a feeling of humanity ensconced in nature. They invoke the historical tradition of the sublime-in-nature: the depiction of aspects of the landscape such as mountains, waterfalls, and other iconic features as sites at which a quasi-religious spirituality might be experienced. The tradition of sublime natural landscapes emerged as a key feature of Romanticism in the eighteenth century (Cronon 1996, 10-12). The Hudson River School of painting, as well as the many poets and writers who were inspired by Hudson Valley locales, are much-discussed exemplars of the American sublime tradition (Driscoll 1997; Schuyler 2012; Novak 2007). The use of the sublime trope in the real estate video thus partakes of a well-established and still culturally-available perspective on Valley landscapes.

In its classic instantiation, the sublime invokes complicated and grandiose sentiments of awe, portent, and mystery (Allen 2011, 24; Johnson 1999, 44). These mixed valences are suggested by the C major/A minor harmonic context of “Coming Winter,” while a sense of the grandiose is reinforced by the cycling four-measure ostinato progression that grounds the piece throughout (example 1A). Each two-measure subphrase of the progression oscillates between temporary relaxation on the opening subdominant and rising energy as it progresses towards the dominant. The repetition of this rise and fall, coupled with the addition of progressive layers of texture, creates wave-like arcs of growth and, ultimately, with the climactic beat drop at m. 27, heroic triumph. The invocation of the sublime implies that to inhabit such a landscape is no small thing: Lightning Tree Farm, as it emerges from the video, is an observer-based landscape of heroism and purpose. As each iteration of the four-chord ostinato passes relentlessly into the next, its presence as a grounding undercurrent throughout creates a parallel to the natural environs of Lightning Tree Farm. The musical tradition of depicting nature via “contained movement” (Johnson 1999, 65–69) portrays the landscape as immutable, cyclical, and fundamentally a background context for the action of dynamic humanity.

Figure 6. Perceived intensities of biophony and anthrophony at three sites in Millbrook, NY.

In contrast to this characterization, the data from soundscape observations in example 2, figure 3, and figure 6 shows human and non-human sounds to be interdependent and reflective of a series of variable rhythms. Rather than an easily-graspable progression, they move to the logics of species mix, seasonality, daylight, geographical features, temperature, and the built environment. At the Uplands Farm site, for instance, proximity to a pond and marshy areas means chorus frogs (spring peepers) and tree frogs sound prominently in the 9:00 p.m. spring soundscape (example 2H). By July, birds comprise much of the biophonic soundscape at Uplands and on Andrew Haight Road and the 9:00 p.m. observations (examples 2O, 2V), taking place after they have gone to sleep, are noticeably quieter. On Franklin Avenue, both biophony and anthrophony are patterned by human activity, sparser at 6:00 a.m. (examples 2A, 2P) and 9:00 p.m. (examples 2D, 2S) and with an increasing prevalence of human voices and footsteps, dogs, and vehicle traffic during business hours at 11:00 a.m. (examples 2C, 2Q) and 4:00 p.m. (examples 2R). Soundscape at Uplands Farm reflects the logic of herd management; the temperature during the 4:00 p.m. observation done on July 5 (example 2L) was an unusually hot 88°F and the soundscape was dominated by barn fans that circulate air to keep the dairy herd cool.

The intensity and duration of extreme summer heat, relatively uncommon in upstate New York but forecasted to increase in frequency as the effects of global warming become more pronounced (Horton et al. 2014, 10–13), is a large-scale illustration of how soundscape ecology data counteract the sense of immutable, unchanging nature that emerges from the real estate video. Sueur, Krause, and Farina (2019) demonstrate that patterns of biophony and geophony are changing as seasonal rhythms shift and break down and the landscape is transformed by temperature and precipitation disruption. The video’s formulation of nature, rooted in the sublime tradition, elides the politics of climate change and proffers instead an unchanging and easily graspable natural world. The cyclical ostinato, in particular, encourages us to hear past both near- and long-term variations and changes in soundscape, conceptualizing it as so-much sonic wallpaper for human agency within the landscape.

Against the ostinato’s backdrop, subsequently-introduced melody instruments fill the musical scene with a depiction of human subjectivity. At m. 17, the texture is enlivened by the appearance of solo cello, which inhabits the landscape as a lone actor immersed in a world of elegant isolation. The bass-clef tessitura and timbre of the cello implies a normative male subjectivity. Indeed, Denise Von Glahn (2013, 22) notes multiple gender-coded differences in representations of American places in her study of American women’s approaches to composing nature- and place-based music. The tradition of representing American place that “Coming Winter” invokes, blending orchestral resources and valences of the sublime in a celebration of large, “iconic” natural phenomena, is historically dominated by masculine coding (and male composers). The cello serves as a sonic double for the imagined subjectivity of the prospective (male) buyer, who tours the home alone except for menials such as the car driver and helicopter pilot.

Anthrophony and Biophony

The tradition of the Romantic sublime in music has its parallel in characterizations of soundscape bathed in mystery and heroism. Within the tradition of sublime soundscapes in the Hudson Valley, these descriptions emphasize two related features: its quiet/silence and its non-city status. Juxtaposed with New York City, “quiet” and “silence” have been made central to the characterization of the aural profile of the Valley and are twinned to its associations with pastoral beauty. As development and human encroachment accelerated along the banks of the lower Hudson River in the 1800s, the silence to be found in points north was newly celebrated. In this context, I have previously noted (Groffman 2019, 16) that Thomas Cole heard in the “silence” of midnight and mountains the same mixed emotional nuances of the musical sublime, trading on a feeling of pleasurable dread—spirituality, adventure, and solitude packaged together in one experience. In a related use of “quiet,” Washington Irving characterizes the Hudson Valley setting of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1983, 1058) as “one of the quietest places in the whole world.”

Not far from this village, perhaps about two miles, there is a little valley or rather lap of land among high hills, which is one of the quietest places in the whole world. A small brook glides through it, with just murmur enough to lull one to repose; and the occasional whistle of a quail or tapping of a woodpecker is almost the only sound that ever breaks in upon the uniform tranquility.

I recollect that, when a stripling, my first exploit in squirrel-shooting was in a grove of tall walnut-trees that shades one side of the valley. I had wandered into it at noontime, when all nature is peculiarly quiet, and was startled by the roar of my own gun, as it broke the Sabbath stillness around and was prolonged and reverberated by the angry echoes. If ever I should wish for a retreat whither I might steal from the world and its distractions, and dream quietly away the remnant of a troubled life, I know of none more promising than this little valley.

—Washington Irving, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820) (Irving 1983, 1058)

In the dense forest where the squirrel lives,

And somber shadows fill the tree roofed space;

Where nature her still benediction gives,

And the dead year lays off its crown of grace –

How restful, to one tired with city streets,

To watch the frolic of the chickadee,

To feel the leaf packed carpet, and to chase

The silver runnel, gurgling to the sea.

There are no splendors that were seen in May,

I find no laurel tinct by opulent June;

But in the bleak, dun February day,

With the caw of crows and the sharp air in tune,

I love to wait till the northern trumpets blow,

And homeward walk through flakes of riotous snow.—Joel Benton (1832-1911), “The Winter Woods” (undated) (Wahlberg, 2008, 54)

For Irving, “quietness” means a lack of anthrophony, made part of his larger project to portray the Hudson Valley as a mythological retreat from the sordid world of progress found in cities. Thus, he juxtaposes the sounds of anthrophony—the “roar” and “angry echoes” of his gun—with non-human and religiously-inflected quiet. Joel Benton, too, compares favorably the stillness of a Valley forest soundscape, to which he ascribes a divine, spiritual quality, with “city streets.” Contemporary marketing materials about the Hudson Valley continue this tradition through emphasis on the landscape as one of quiet and retreat (Thomas 2019). Such characterizations inevitably bring with them a classed and racialized rhetoric, sounding the city not only as loud but as racially heterogeneous, dirty, and morally suspect (Llano 2018, 4).

Figure 7 shows that the soundscape of Millbrook is not silent, or really, even all that quiet.

Figure 7. Ambient noise levels at three sites in Millbrook, NY.

However, the aural profile at all three sites is demonstrably one in which ambient noise levels are quieter when compared to New York City, where ambient levels can be in excess of 70 dBa for sustained periods and “disruptive noise exposure” is increasingly recognized as a risk to mental and physical health (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygenie 2014; Rueb 2013). Figure 6 shows that Millbrook soundscapes also contain a relatively even balance between biophony and anthrophony in comparison to anthrophony-heavy urban soundscapes. Of all sites, the Haight Road soundscape adjacent to Lightning Tree Farm is the most isolated and inaccessible of the three sites and, in the July 11:00 a.m. soundscape, contains the lowest ambient noise levels and the highest profusion of biophony. Although not high in amplitude (see figure 3A, Biophony, Average maximum power), these biophonic sounds are prominent, occupying a high percentage of the soundscape duration in comparison to Franklin Ave. and Uplands Farm; and they are diverse, comprising ten identified species of birds, as well as insects and a squirrel. Such diversity can be attributed to the presence of trees and hedges for shelter and the relative lack of human presence, since birds will fly away or switch from song to alarm calls in the case of intrusive human presence.

One reflection of the income and social inequality that characterizes many societies today is a greater access to “green” amenities for wealthier, whiter populations (Hines 2010; Sandberg 2014; Anguelovski et al. 2018) and, conversely, greater exposure to environmental catastrophe and hardship for poorer communities and people of color (Clark et al. 2007). This detail was laid bare by COVID-19 lockdowns, during which wealthier New Yorkers retreated to second homes while poorer city residents, who had neither the option of relocating or of working remotely faced the brunt of the pandemic’s effects (Fisher and Bubola 2020). The soundscape data bear this situation out on a granular level: the quiet and profusion of biophony in and around Millbrook reflects broad patterns of class and access predicated on the control, and exclusion, of human presence.

Further historicizing the roots of Millbrook’s ambient noise levels and the balance of anthrophony/biophony can explicate its present profile. Early European colonizers of the Americas heard quiet soundscapes as threatening, a palpable aural gap that demanded modification, domination, and filling up with human sounds (Coates 2005, 642–643). With ears steeped in those settler traditions, it is possible to hear Haight Road as an improved “middle” space between city and wilderness (Marx 2000, 128), offering the pleasures of nature with its rougher elements sanded off; Finney (2014, 117) notes that it may well be perceived very differently by communities whose experience of “natural” or pastoral landscapes are marred by histories of slavery, land appropriation, and violence.

Figure 8. Perceived B/G/A and ambient sound level on Andrew Haight Road over a ten-minute observation, 11:00 a.m., July 5, 2018.

Figure 8 shows how the biophony of the July 11:00 a.m. soundscape, which maintains a static level through, is overwhelmed at regular intervals by the entrance of car motors. The cars create sonic events dramatically larger in average frequency ratio and average maximum power (figure 3A, Anthrophony) than anything else in the soundscape, serving to momentarily obliterate perception of biophony or geophony. As in Irving’s example of anthrophony intruding upon the soundscape, in the wake of the “angry echoes” of the car, the threshold of perceptual volume is raised. The sounds of bird, insect, and animal calls, lower in amplitude, recede into the sonic background.

Thus Lighting Tree Farm is made “quiet,” if only in comparison with other, louder sites and because of perceptual significance granted to anthrophonic sound. In contrast to early descriptions of biophony that unnerved and disturbed the sleep of colonizers (Donck 2008, 42), the density of biophony is firmly checked by human alteration of the landscape and the species within it. The primeval forest that obsessed early colonizers, in which lurked both wild animals and potentially hostile Native Americans, is gone (Groffman 2019, 21–22). In my own hearing of the ObL, the interaction of anthrophony and biophony of Andrew Haight Road establishes the character of the landscape as one generously endowed with natural resources but fundamentally domesticated by humanity.

The ObL of the real estate tour reflects the same traditions of settler colonialism as the soundscape accounts discussed here: it proposes a hearing of the relationship between biophony and anthrophony through its use of the cycling “nature ostinato” as a background that, once introduced, fades into the perceptual background to make room for the cello, representing a Euro-American male subjectivity. The music thus proposes that any overwhelm of biophony by anthrophony is not a covering up or a destruction of more delicate, non-human sounds, but simply the appropriate sonic scheme: nature as context for the human, the perceptually marked element.

There is, seemingly, something of a contradiction between hearing the soundscape as one of quiet, pastoral peace and the tradition of the more amped-up, awe-inspiring sublime implied by the music. Yet Cronon (1996, 12) illustrates that by the late nineteenth century, the sublime became “tamed” by human development of natural landscapes and burgeoning travel and tourism industries; today, he notes (with a certain aptness to the present study) our conception of the sublime “has been so watered down by commercial hype and tourist advertising that it retains only a dim echo of its former power” (10). Lightning Tree Farm, in the video, offers a container to encompass an all-of-the-above experience: domestic tranquility and pastoral peace heightened by a heroic sense of the sublime. Contemporary ad copy skillfully adopts the misanthropic and classed valences latent in the accounts of nineteenth-century observers. The non-human world, it seems, is best enjoyed without too many humans around. This stance creates a permission structure to inhabit the property and, thereby, to embody a sense of natural spaces kept to oneself.

The Character, Depth, and Patina of Time

I have shown that multiple elements of “Coming Winter” gesture backwards in time, tying the real estate video to historical traditions via elements of neo-Romantic instrumentation and invocation of the sublime. This resonates with many of the visual elements of the video and with descriptions of the Millbrook countryside as steeped in the antiquarian traditions of equestrian pursuits and the English foxhunt. The vintage aesthetic often found on Millbrook’s estates is summed up by an Equestrian Living profile of a Millbrook designer in whose work “[n]othing is shiny, new, or fussy; each element has the character, depth, and patina of time” (EQ Living, n.d.). The retro nature of the video is evident in the opening shot of a wood-paneled car that ferries the prospective buyer onto the estate. As the car leaves the paved main road adjoining the estate and turns on to the packed dirt driveway, the viewer is drawn back in time and into “the dominant property in the midst of Millbrook hunt country.” The visuals depict the estate (“more than a home…a lifestyle statement”) in fashions that draw heavily on Anglo-American cultural trappings of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Vintage items pop up throughout the video: antique books stand positioned on a desk (video time point 1:17), Greco-Roman statuary flanks the pool (0:34), gilt-frame oil paintings adorn the walls (0:48, 1:19). These choices, like the use of the classically-tinged music, elide the highly modern context of a property marketed via video, posted to a streaming service, and soundtracked by a wholly-electronic score.

The Town of Washington (inside of which lies the village of Millbrook) declares in its Comprehensive Plan for land use that it seeks to “remain a rural community with great scenic beauty,” by, among other things, protecting “beautiful historic landscapes” and the Village’s “historic character” (Beaumont et al. 2015, 37). Residential and business development is frequently met with opposition (Davis 2021). As a result, the historical turn evident at Lightning Tree Farm is echoed in many aspects of the village’s broader soundscape. Much of the individual-based soundscape on Andrew Haight Road resembles what might have been heard on a spring or summer day at the turn of the twentieth century. The appeal of an item like the antique car is not merely in its look: rather, a vintage car produces a distinct sound, bodily feel, and driving experience via antique motor, tires, and brakes (Smith 2018). Gravel and dirt roads, pictured at the entrance to the estate (video time point 00:14) and heard resounding under the tire wheels in the Haight Road soundscape (example 2K, figure 3A, figure 8), abound in Millbrook despite the additional maintenance they require compared to paved ones. They preserve elements of the landscape that are perceptually marked as historical and non-modern. Driving on a dirt road in a vintage car powerfully recreates an immersive biosensory experience from the early 1900s; sights and sounds of the individual-based landscape together engineer a vintage observer-based landscape.

A crucial point at which “Coming Winter” is deployed to gloss contradictions between the vintage ObL promoted by the video and the contemporary actuality of IbL in Millbrook is in its final moments (mm. 27–end). In the video’s concluding sequence, there is a dramatic change in the visuals that have previously highlighted vintage items: the appearance of the helicopter and the showcasing of the property’s most lavish feature, a private helipad. The sights and sounds associated with powerful aircraft engines are common in Millbrook. The skies above Millbrook are frequently filled with commercial traffic from New York City, White Plains, Newburgh, Albany, and smaller airports that service privately-owned aircraft (figures 3A, 3B, 3C, Anthrophony).

The appearance of the helicopter is preceded by the conclusion of the cello’s solo passage and a brief lull (m. 25). Accelerating drums introduce the triumphant ending (m. 27), made positively epic by chorusing string orchestra, massive bass, and churning synth arpeggiations. I hear the chorusing strings and figuration that accompany the helicopter’s arrival as a musical representation of the helicopter sound, transforming what might be considered a disruptive and unpleasant noise into a grand musical effect. The string timbre creates an aural link to the cello; the solo subjectivity that toured the house as aristocratic hero now looks out from behind the pilot’s shoulder, descending into his would-be property with more-than-human multiplicity. The hypermodern sights and sounds of the helicopter are sublimated into a world with “the character, depth, and patina of time.” At the video’s climax, the visuals, which have drawn in to show the detail of individual rooms, jump outward in scale (video time point 1:50): panning shots of the house, the grounds, fields, and forests emphasize once again Lightning Tree Farm’s embeddedness within the natural landscape. As the video ends the helicopter recedes into natural splendor (1:59); the music’s sudden calm a moment later (m. 35) glosses the aircraft’s disruptiveness to the aural commons, folding it into visuals of the beautiful, pastoral world which the viewer is exhorted to purchase.

Conclusion

This paper has suggested some ways in which the consideration, in tandem, of the experience of cultural artifacts and physical soundscapes may elucidate a richer understanding of both kinds of experience. As much as a physical fact, “the environment” is an intellectual category, and a profoundly ideological one. Many Hudson Valley soundscapes are created and sustained for those with sufficient wealth and agency to monopolize the pastoral beauty they contain. My research here illustrates that examination of our present moment’s sounding of nature in music and soundscape is an avenue for exploring the schisms of class and race that fuel politicized debates about environmental conservation and stewardship in the United States.

Diane di Prima (1971) asks: “Are we, indeed, welcome at Millbrook / In the great estate houses…Are we, indeed, welcome to the fruits of the earth.” For di Prima, the two questions seem ineluctably linked; that they might not be is the hope of this article. My investigation, on its own, will not rectify environmental injustices or inequalities of access. But as Lawrence Buell (2005, ii) writes: “For technological breakthroughs, legislative reforms, and paper covenants about environmental welfare to take effect, or even to be generated in the first place, requires a climate of transformed environmental values, perception, and will.” In focusing on environmental values and perception as they relate to the marketing of a Hudson Valley landscape, I have sought to make more explicit the rhetorical and affective logic underpinning the linkages between modern capitalist ideology and human relations to the natural world. A more just ecological future begins with the continued unpacking of the American pastoral ideology, interrogating our hearing of the world around and within us.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the University of Pittsburgh and Southern Connecticut State University for funding aspects of this research project. Thanks also go to the two reviewers of this article, whose comments spurred a substantial revision, and to attendees at the American Musicological Society’s 2019 meeting in Boston, MA, who also offered valuable feedback.

References

Allen, Aaron S. 2011. “Symphonic Pastorals.” Green Letters 15 (1): 22-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/14688417.2011.10589089.

Allen, Aaron S. 2014. Ecomusicology. In The Grove Dictionary of American Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Allen, Aaron S, Jeff Todd Titon, and Denise Von Glahn. 2014. “Sustainability and Sound: Ecomusicology Inside and Outside the Academy.” Music and Politics VIII (2). https://doi.org/10.3998/mp.9460447.0008.205.

Anguelovski, Isabelle, James J. T. Connolly, Melissa Garcia-Lamarca, Helen Cole, and Hamil Pearsall. 2018. “New Scholarly Pathways on Green Gentrification: What Does the Urban ‘Green Turn’ Mean and Where Is It Going?” Progress in Human Geography: 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518803799.

Beaumont, Thomas, Don Hanson, Frank Genova, Jim Shequine, Joshua Mackey, Jeremy Baker, Jesse Bontecou, Kate Farrell, Maureen King, Tim Marshall, Karen Mosca, and David Strayer. 2015. Town of Washington Comprehensive Plan. Millbrook: Town of Washington Board.

Benham, Stanley H., Sr. 2005. Rural Life in the Hudson River Valley 1880-1920, edited by Virginia Benham Augerson and Stanley H. Benham, Jr. Poughkeepsie, NY: Hudson House.

Brandon, Elissaveta M. 2020. “The Challenge of Affordable Housing in the Hudson Valley.” The River, November 19, 2020.

Buell, Lawrence. 1995. The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Buell, Lawrence. 2005. The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Cannavò, Peter F. 2001. “American Contradictions and Pastoral Visions: An Appraisal of Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden.” Organization & Environment 14 (1): 74-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026601141004.

Chatterjee, Piyusha, and Steven High. 2017. “The Deindustrialisation of Our Senses: Residual and Dominant Soundscapes in Montreal’s Point Saint-Charles District.” In Telling Environmental Histories: Intersections of Memory, Narrative and Environment, edited by Katie Holmes and Heather Goodall, 179-210. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Clark, W. C., R. W. Kates, J. F. Richards, J. T. Mathews, W. B. Meyer, B. L. Turner Ii, Steward T. A. Pickett, Christopher G. Boone, and Mary L. Cadenasso. 2007. “Relationships of Environmental Justice to Ecological Theory.” The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 88 (2): 166-170. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9623(2007)88[166:ROEJTE]2.0.CO;2.

Coates, Peter A. 2005. “The Strange Stillness of the Past: Toward an Environmental History of Sound and Noise.” Environmental History 10 (4):636-665. https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/10.4.636.

Cooley, Timothy, Aaron S. Allen, Ruth Hellier, Mark Pedelty, Denise Von Glahn, Jeff Todd Titon, and Jennifer C. Post. 2020. “Call and Response: SEM President’s Roundtable 2018, ‘Humanities’ Responses to the Anthropocene’.” Ethnomusicology 64 (2): 301-301. https://doi.org/10.5406/ethnomusicology.64.2.0301.

Cooper, James Fenimore. 1985. The Leatherstocking Tales, Volume 1. New York: Literary Classics of the U.S.

Corbin, Alain. 1998. Village Bells: Sound and Meaning in the Nineteenth-Century French Countryside. Translated by Martin Thom. New York: Columbia University Press.

Corbin, Alain. 2018. A History of Silence: from the Renaissance to the Present Day. Translated by Jean Birrell. Cambridge, MA: Polity.

Cronon, William. 1996. “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Environmental History 1 (1): 7-28. https://doi.org/10.2307/3985059.

Davis, Nicole. 2021. “Millbrook Residents Fight Effort to Turn Migdale Castle Into Luxury Resort.” Times Union, March 29, 2021.

di Arpino, Carmine. 1988. A History of the Town of Washington and Millbrook. Millbrook, NY: Millbrook Central Press.

di Prima, Diane. 1971. Kerhonkson Journal 1966. Berkeley, CA: Oyez.

Donck, Adriaen van der. 2008. A Description of New Netherland. Translated by Diederik Willem Goedhuys. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Doughty, Karolina, Michelle Duffy, and Theresa Harada. 2019. “Sounding Places: An Introduction.” In Sounding Places: More-than-representational Geographies of Sound and Music, edited by Karolina Doughty, Michelle Duffy and Theresa Harada, 1-7. Northhampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Driscoll, John Paul. 1997. All That is Glorious Around Us: Paintings from the Hudson River School. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Droumeva, Milena, and Jordan Randolph, eds. 2019. Sound, Media, Ecology. London: Palgrave Macmillian.

Equestrian Living, n.d. “Tailgating as an Art.” Accessed December 15, 2016. https://eqliving.com/tailgating-as-an-art/.

Farina, Almo. 2014. Soundscape Ecology: Principles, Patterns, Methods and Applications. Dordrecht: Springer.

Farina, Almo, and Andrea Belgrano. 2006. “The Eco-field Hypothesis: Toward a Cognitive Landscape.” Landscape Ecology 21 (1):5-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-005-7755-x.

Farina, Almo, and Nadia Pieretti. 2014. “From Umwelt to Soundtope: An Epistemological Essay on Cognitive Ecology.” Biosemiotics 7 (1): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12304-013-9191-7.

Finney, Carolyn. 2014. Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Fisher, Max, and Emma Bubola. 2020. “As Coronavirus Deepens Inequality, Inequality Worsens Its Spread.” The New York Times, March 15, 2020.

Ghee, Joyce C., and Joan Spence. 2000. Taconic Pathways through Beekman, Union Vale, LaGrange, Washington, and Stanford. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

Grimley, Daniel M. 2006. Grieg: Music, Landscape and Norwegian Identity. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

Grimley, Daniel M. 2011. “Music, Landscape, Attunement: Listening to Sibelius’s Tapiola.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 64 (2):394-482.

Grimley, Daniel M. 2018. Delius and the Sound of Place. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Groffman, Joshua. 2019. “In Truth, the Forest Hears Each Sound: Sounding Nature and Ideology in New York’s Hudson Valley.” Music and Politics 13, no. 2 (2): 31.

Guy, Nancy. 2009. “Flowing Down Taiwan’s Tamsui River: Towards an Ecomusicology of the Environmental Imagination.” Ethnomusicology 53 (2): 218-248.

Guy, Nancy. 2019. “Garbage Truck Music and Sustainability in Contemporary Taiwan: From Cockroaches to Beethoven and Beyond.” In Cultural Sustainabilities: Music, Media, Language, Advocacy, edited by Timothy J. Cooley, 63-74. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Guyette, Margaret Q., and Jennifer C. Post. 2016. “Ecomusicology, Ethnomusicology, and Soundscape Ecology: Scientific and Musical Responses to Sound Study.” In Current Directions in Ecomusicology: Music, Culture, Nature, edited by Aaron S. Allen and Kevin Dawe, 40-56. New York: Routledge.

Haag, Matthew. 2020. “New Yorkers Are Fleeing to the Suburbs: ‘The Demand Is Insane’.” The New York Times, August 30, 2020.

Hays, Samuel P., and Barbara D. Hays. 1987. Beauty, Health, and Permanence: Environmental Politics in the United States, 1955-1985. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hines, J. Dwight. 2010. “Rural Gentrification as Permanent Tourism: The Creation of the ‘New’ West Archipelago as Postindustrial Cultural Space.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (3):509-525. https://doi.org/10.1068/d3309.

Hogg, Bennett. 2015. “Healing the Cut: Music, Landscape, Nature, Culture.” Contemporary Music Review 34 (4): 281-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2016.1151174.

Horton, Radley M., Daniel A. Bader, Cynthia Rosenzweig, Arthur T. DeGaetano, and William Solecki. 2014. Climate Change in New York State: Updating the 2011 ClimAID Climate Risk Information Supplement to NYSERDA Report 11-18 (Responding to Climate Change in New York State). Albany: New York State Energy Research and Development Authority.

Howes, David. 2005. “Introduction: Empire of the Senses.” In Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader, edited by David Howes, 1–17. Oxford: Berg.

HudsonValley360. 2018. “Airbnb Beginning to Have Positive Impact on the Hudson Valley Real Estate Market.” April 10, 2018. https://www.hudsonvalley360.com/article/airbnb-beginning-have-positive-impact-hudson-valley-real-estate-market.

Ingram, David. 2010. The Jukebox in the Garden: Ecocriticism and American Popular Music Since 1960. New York: Rodopi.

Irving, Washington. 1983. History, Tales, and Sketches. New York: Literary Classics of the United States.

Järviluoma, H., M. Kytö, B. Truax, H. Uimonen, and N. Vikman. 2009. Acoustic Environments in Change. Tampere: University of Tampere.

Johnson, Julian. 1999. Webern and the Transformation of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krause, Bernard L. 1987. “Bio-acoustics: Habitat Ambience and Ecological Balance.” Whole Earth Review (57):14.

Krause, Bernard L., Stuart H. Gage, and Wooyeong Joo. 2011. “Measuring and Interpreting the Temporal Variability in the Soundscape at Four Places in Sequoia National Park.” Landscape Ecology 26 (9):1247-1256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-011-9639-6.

Llano, Samuel. 2018. “Mapping Street Sounds in the Nineteenth-Century City: a Listener’s Guide to Social Engineering.” Sound Studies:1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/20551940.2018.1476305.

Lonely Planet. 2012. “Top 10 US Travel Destinations for 2012.” https://web.archive.org/web/20190814181322/https://www.lonelyplanet.com/usa/travel-tips-and-articles/top-10-us-travel-destinations-for-2012/40625c8c-8a11-5710-a052-1479d277fd66.

Lorimer, Hayden. 2005. “Cultural Geography: The Busyness of Being ‘More-Than-Representational’.” Progress in Human Geography 29 (1):83-94. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132505ph531pr.

Marx, Leo. 2000. The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Matsinos, Yiannis G., Antonios D. Mazaris, Kimon D. Papadimitriou, Andreas Mniestris, George Hatzigiannidis, Dimitris Maioglou, and John D. Pantis. 2008. “Spatio-temporal Variability in Human and Natural Sounds in a Rural Landscape.” Landscape Ecology 23 (8):945-959. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-008-9250-7.

Mitchell, Tony. 2009. “Sigur Rós’s Heima: An Icelandic Psychogeography.” Transforming Cultures eJournal 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.5130/tfc.v4i1.1072.