by Emily Doolittle

Abstract

The hermit thrush (Catharus guttatus) is a small songbird, widespread across North America. During breeding season, which is spent in the western and northeastern United States and the southern half of Canada, the hermit thrush sings a song which is widely considered beautiful. This song has featured prominently in the scientific writing, poetry and music of the primarily Anglophone settlers to these regions for the past 200 years, and likely since long before then in the orally transmitted knowledge and folklore of Indigenous peoples. In this interdisciplinary, ecomusicologically-focused paper, I draw on primary scientific, literary and musical sources, as well as on related scholarship from the fields of ecomusicology, zoomusicology, environmental history, literary history, and the biological sciences to tell the story of how hermit thrush song became a symbol of English-speaking American and Canadian cultural identity from the mid-nineteenth through mid-twentieth centuries. In the heyday of the hermit thrush’s cultural potency, writers such as John Burroughs (1837–1921), Walt Whitman (1819–1892), and the Canadian “Confederation Poets” (born in the decade surrounding Canadian confederation) popularized an image of the bird as admirably solitary, aesthetically cultured, and spiritually inspired: this overlapped perfectly with a transcendentalism-influenced sense of self that appealed to much of their readership. The burgeoning mid-nineteenth-century literary magazine industry spread this imagery far and wide, particularly among the North American middle classes (Lupfer 2010, 381, 390; Glazener 1997, 259). From the mid-twentieth century onwards, urbanization and technologically-mediated changes in the ways people relate to the natural world caused the hermit thrush to lose relevance as a cultural symbol, but vestiges of its symbolic power remain.

“Hermit Thrush, 1. Male 2. Female (Plant: Robin Wood.)” From The Birds of America: From Drawings Made in the United States and their Territories, vol. 3, by John James Audubon, 1841. General Research Division, The New York Public Library, New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-72ac-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Introduction

The hermit thrush (Catharus guttatus) is a small songbird, widespread across North America. During breeding season, which is spent in the northeastern and western United States and the southern half of Canada, male hermit thrushes sing a distinctive, flutey song that is based on the harmonic series and is often described as “musical” or “melodious.”

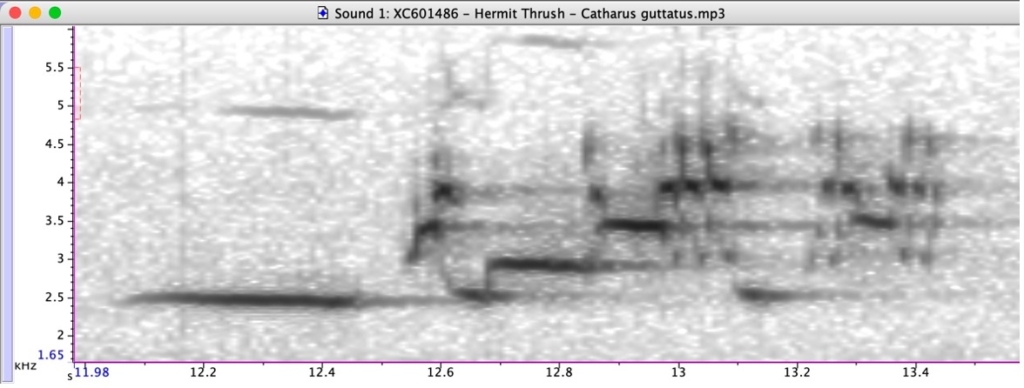

Figure 1. Spectrogram of a hermit thrush song. Each male hermit thrush sings 6–12 “song-types,” each of which consist of a long “introductory whistle,” followed by a series of fast, flutey warbles. For further description of the song, see Doolittle et al 2014, Roach et al. 2012, Kroodsma 2005, 255, and Rothenberg 2005, 53. For listening, here are a few particularly characteristic examples of the song from the Xeno-Canto database. This song in the spectrogram was recorded by McPherson (2020), and the spectrogram was made using RavenPro 1.6.

As their common name suggests, hermit thrushes are reclusive: even people living within their breeding range may not be familiar with their song unless they spend time in the wilderness. Though they sing primarily at dawn and dusk, hermit thrushes are also noted for singing in the afternoon when most other birds are silent.

For the past 200 years, hermit thrush song has featured prominently in the scientific writing, poetry and music of the primarily Anglophone settlers who live within the bird’s breeding range, and likely since long before then in the orally transmitted knowledge and folklore of Indigenous peoples. While storytelling, poetic, scientific, and musical approaches may initially seem so different as to be unrelated, they all fit together as part of a single narrative about how people, coming from a variety of perspectives, have heard, understood, and represented the hermit thrush throughout history, with these changing understandings revealing as much about the developing cultural identity of English-speaking North Americans as they do about the hermit thrush itself. In this interdisciplinary, ecomusicologically-focused paper, I draw on primary scientific, literary and musical sources, as well as on related scholarship from the fields of ecomusicology, zoomusicology, environmental history, literary history, and the biological sciences (Allen and Dawe 2016, 1–2; Allen 2011, 392) to trace this narrative, from the earliest appearance of the hermit thrush in Indigenous legends and in eighteenth-century European taxonomical treatises through to the use of hermit thrush song as a potent, transcendentalism-tinged symbol of English-speaking American and Canadian cultural identity in the late nineteenth through mid-twentieth centuries. Though more recent representations of hermit thrush song tend more towards dispassionate observation and reflection than towards the heightened emotional signification of earlier generations, echoes of the song’s symbolic resonance remain.

“Sacred Song”: The Hermit Thrush of Haudenosaunee Legend (oral tradition)

What may be the oldest surviving account of how humans have conceptualized hermit thrush song is a Haudenosaunee (Iroquoian) tale called variously The Legend of the Hermit Thrush (Oneida Nation 2020), Why the Hermit Thrush is so Shy (Powers 1917, 79), or similar. Though traditionally told orally, there are written retellings of this story from several member tribes of the Haudenosaunee Confederation, including from the Mohawk, Oneida, and Onondaga Nations. Perhaps the best known of these is the book The Sacred Song of the Hermit Thrush, first published in 1993 by Mohawk storyteller and teacher Tehanetorens, also known as Aren Akweks and Ray Fadden (1910–2008). In Tehanetoren’s telling, the Good Spirit offers to give songs to the birds, with the most beautiful song to go to the bird who flies highest. The hermit thrush, knowing he is too small to fly highest on his own, rides part of the way on the back of an eagle, thus saving his energy so he can continue up to the Spirit World after the eagle can fly no farther. The hermit thrush learns the most beautiful song from the Spirit World, but becomes embarrassed for having cheated, so hides away in the forest. The other birds, recognizing the special beauty of the hermit thrush’s song, all fall silent when he sings.

Tracing the origins of any story from an oral tradition is difficult, but Tehanetorens’s son John Kahionhes Fadden, now in his 80s, remembers hearing the story from earliest childhood, and believes Tehanetorens learned the story from other Haudenosanee elders (J. K. Fadden, email with author, 2020). Though the protagonist species differs, the plot of this Haudenosanee hermit thrush story bears close resemblance to the medieval Irish legend of The Eagle and the Wren or The Wren-King. In the Irish story, the birds have a flying contest to determine who will be king of the birds. The wren, like the hermit thrush, knows he is too small to fly highest, so he rides on the back of an eagle until the eagle can fly no further, and then continues up to the heavens on his own, where he is declared king. In some versions of The Wren-King, the wren is ashamed of cheating and hides away, like the hermit thrush, while in others he is celebrated for his cleverness, or the eagle is crowned king after the wren’s deceit is discovered (Lawrence 1997, 24–40).

Whether the shared aspects of the Haudenosaunee and Irish versions of this story represent independent developments of a similar story or result from cultural exchange is currently unknown. Frequent contact between the Haudenosaunee and settlers from the British Isles, including the adoption of settlers (of all ages) into Haudenosaunee tribes, suggest that story sharing was likely. (Tehanetorens himself had been adopted as an adult into the Mohawk nation, and was also married to Christine Chubb, a Mohawk woman [Otis 2018, 210, 232, 238]). In any case, whether adapted from the Irish tale or independently arising, the Haudenosaunee tale does not merely present an alternate protagonist species, but homes in on the hermit thrush’s distinctive characteristics—its notably beautiful song, its solitary nature, and its tendency to sing when other birds are silent—along with giving the song an otherworldly origin which sets it apart from the songs of other birds. The reclusiveness of the hermit thrush, the rare beauty of its song, and a connection with the spiritual realm, were to become common themes for European explorers and settlers in North America as well, whether they were writing as poets, naturalists or scientists, or musicians.

“Harsh, Raucous and Monotonous”: The Hermit Thrush at the Hands of European-Born Taxonomists (1788–1833)

The earliest written scientific references to the hermit thrush are no easier to disentangle than those from oral traditions. Scattered mentions of a “hermit thrush” appear in late eighteenth-century treatises by Swedish “Father of Taxonomy” Carl Linneus (1707–1788; Linné and Gmelin 1789, 833) and French naturalist George Louis LeClerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788; Buffon 1792, 321), but they refer to a Philippine bird (Merula solitaria phillipensis), not the North American hermit thrush. By the early nineteenth century, the name “hermit thrush” was more reliably attached to the modern hermit thrush by such writers as Prussian taxonomist Peter Pallas (1741–1811) in 1811 (Hoyo et al 2005, 705), British naturalists William John Swainson (1789–1855) and John Richardson (1787–1865) in 1831, and German ornithologist Jean Louis Cabanis (1816–1906) in 1845 (Coues 1878, 20).

These late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century naturalists were from, and primarily resident in, Europe. They often relied on dead specimens sent from abroad and word-of-mouth reports from friends, rather than direct observation, to learn about the species they classified. Typically their aim was categorization of the flora and fauna of the world, rather than detailed understanding of individual species or bioregions. Long-term, in-depth observation of behaviour thus played little or no role in their categorization or understanding of the animals they studied. Furthermore, these authors’ writings were often suffused with an explicit or tacit belief in the primacy of European species. The highly influential Comte de Buffon, in particular, had popularized the racist idea that European forms—of plants, animals, and even people—were the original prototypes, and species and races found on other continents were inherently “degenerate” (Dugatkin 2019, 1–2).[1] As far as animals were concerned, this applied not only to phenotype, but also to all aspects of behaviour, including song. Though Buffon for some reason approved of the mockingbird, he confidently proclaimed that the voices of other North American birds were “harsh, raucous, and monotonous”—this despite his never having traveled to North America (Buffon 1792, 288).

Even when European-born scientists began to spend more time in the Americas, they often arrived with Eurocentric preconceptions about what they might find there. Due, perhaps, to the combination of these prejudices with the reclusive nature of the hermit thrush and the ease of confusing it with similar species (in particular, the Swainson’s thrush, the veery, and the wood thrush), scientists remained unaware of hermit thrush song throughout the first few decades of the nineteenth century. Scottish-American “Father of American ornithology” Alexander Wilson (Ord 1828, iv), for example, believed the hermit thrush to be entirely mute, aside from “an occasional squeak, like that of a young stray chicken” (Wilson et al. 1831, 121), while the Haitian-born, French-American ornithologist and artist John James Audubon, author of the celebrated Birds of America, allowed it a “single plaintive note” (Audubon 1831, 30, cited in Coues 1878, 33).

A “Cheerful and Melodious Songster”: Local Observers (1833–1865)

It is not surprising, then, that the earliest written mention of hermit thrush song comes not from one of the grand European-born taxonomists, but from Quebec City-born naturalist “Mrs Sheppard of Woodfield,” née Henrietta [Harriet] Campbell (1786-1858; Creece and Creece 2010, 139), who described the hermit thrush as a “cheerful and melodious songster” who sings with “much sweetness and some variety” (Sheppard 1833, 222). Known for her “extreme patience and accuracy” (Perceval 1825, cited in Shteir and Cayouette 2019, 13-14), Sheppard made notable contributions to the fields of botany, conchology, and ornithology throughout the 1820s and 30s, in particular through her publications in the Transcations of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec and her provision of botanical specimens to William Hooker, director of the Kew Gardens in London and author of the 1840 volume Flora Boreali-Americana (Shteir and Cayouette 2019, 14, 17). Sheppard thus participated in international taxonomical discourse, but as was typical for women of the time, focused on in-depth observation of the species that could be found near her home, rather than on attempts to categorize species worldwide (Von Glahn, 2011, 400; Von Glahn 2013, 16). She was aware of important corrective nature of her work, and was a conscious participant in efforts to prove incorrect “the assertions of Buffon, that the American birds have little or no song, but what is harsh and unmusical” (Sheppard 1833, 222).

The next published mentions of hermit thrush song appear in 1840, in American author Samuel Griswold Goodrich’s children’s encyclopedia, Peter Parley’s Illustrations of the Animal Kingdom: Beasts, Birds, Fishes, Reptiles and Insects, and in English-American zoologist Thomas Nuttall’s A Manual of the Ornithology of the United States and of Canada. Though these authors are writing for very different audiences, they paint a similar image of the hermit thrush: Goodrich describes the bird as “resembling the nightingale in color, and almost equal to it in song” (1840, 186), while Nuttall calls it “scarce inferior to [the Nightingale] in its powers of song,” (1840, 394). The nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos), native to Europe, south-west Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, has a famously beautiful and much celebrated song, but one which is quite dissimilar to hermit thrush song, featuring a fairly continuous stream of repeated warbles, trills, knocks, and whistles (Shippey 1970, 46). That both Parley and Nuttall chose to compare the hermit thrush with the nightingale suggests that they had chosen the nightingale as a way of pushing back against the Eurocentrism of earlier generations of naturalist, rather than simply trying to draw parallels between the specific sounds and structures of the two songs.

“O Holy, Holy”: The Transcendental Hermit Thrush of the North American Nature Essayist (1865–1940s)

North Americans had, of course, always written about the world around them, in personal letters or diaries, newspaper columns, farming almanacs, travel guides, poetry, and stories, as well as in the kinds of local, national, and international scientific and naturalist publications mentioned above. But beginning in the mid-1800s, the establishment and growth of the American literary, general interest magazine industry facilitated the development of a new, distinctively American form of “nature essay,” which aimed to “combine description of particular localities with personal narratives and passages of philosophical reflection” (Snider 1997, 1254). Publications such as The Dial (founded 1840), Putnam’s Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science and Art (founded 1853), The Atlantic Monthly (now The Atlantic, founded 1857), and Scribner’s Monthly (founded 1870, and later to become Century Magazine) took on as their mission the edification of the diverse and growing American middle class, who they sought to reach through easily readable essays that nonetheless touched on weighty matters of morality, spirituality, and philosophy: nature essays fit the bill perfectly (Lupfer 2010). Mid-century nature essayists published by these magazines include Wilson Flagg (1805–1884) who aimed to cultivate a morally uplifting love of nature in the general public (Buckley 2010), and Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) and Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), two of the founding fathers of the American transcendentalist movement, who sought to legitimize transcendentalist religious philosophy by grounding it in natural observation (Snider 1997, 1255–1256). The periodical industry was slower to take off in Canada, but by the early 20th century, Canadian authors such as Charles G. D. Roberts (1860–1943) and William Bliss Carman (1861–1929)—discussed later in their better-known roles as “Confederation Poets”—also contributed to the genre of the transcendentalism-influenced nature essay (Connor 1997, 302–304; Lane 2011, 26-31).

One of the most prominent nineteenth- and early twentieth-century nature essayists was Catskills-born John Burroughs (1837–1921), who brought together the detailed natural observation of writers such as Flagg with philosophical musings deeply influenced by Emerson and Thoreau. Though less famous today, in his lifetime Burroughs was widely considered to represent “not only the highest level of literary achievement, but also the simple, rural life that many middle-class Americans now claimed as their national heritage.” (Lupfer 2010, 390). In his first lead-story nature essay, With the Birds, published in The Atlantic in 1865, Burroughs extolled the virtues of many species of American songbirds, but none more so than the hermit thrush. Burroughs began by tackling the notion that the mockingbird was the best singer, proposing the hermit thrush and two of its close relatives as superior.

The Hermit-Thrush, the Wood-Thrush, and the Veery (Turdus Wilsonii) are our peers of song. The Mocking-Bird… never approaches the serene beauty and sublimity of the Hermit-Thrush. The word that best expresses my feelings, on hearing the Mocking-Bird, is admiration, though the first emotion is one of surprise and incredulity… The emotions excited by the songs of these Thrushes belong to a higher order, springing as they do from our deepest sense of the beauty and harmony of the world. (Burroughs 1865, 522)

He went on to speak more explicitly of hermit thrush song as embodying a calm spirituality, which acts as a corrective to the “hurry and ambition” to which humans are prone.

The song of this Thrush is of unparalleled sweetness and sublimity. There is a calmness and solemnity about it that suggests in Nature perpetual Sabbath and perennial joy. How vain seem our hurry and ambition! Clear and serene, strong and melodious, falling softly, yet flowing far, these notes inspire me with a calm, sacred enthusiasm. I hear him most in the afternoon, but occasionally at nightfall he “pours his pure soprano,” “[d]eepening the silence with diviner calm.” (522–523)

Later in the same essay, Burroughs distinguished the song of the hermit thrush from that of the similar-appearing and more widely familiar wood thrush, using specifically musical terms.

I think his song, in form and manner, is precisely that of the Wood-Thrush,—differing from it in being more wild and ethereal, as well as stronger and clearer. It is not the execution of the piece so much as the tone of the instrument that is superior. In the subdued trills and quavers that occur between the main bars, you think his tongue must be more resonant and of finer metal. In uttering the tinkling, bead-like de, de, de, he is more facile and exquisite; in the longer notes he possesses greater compass and power, and is more prodigal of his finer tones. How delicately he syllables the minor parts, weaving, as it were, the finest of silver embroideries to the main texture of his song! (522–523)

The underlying message of the hermit thrush song here—that we must get away from the “vain… ambition” (523) of humanity to experience the “deepest sense of the beauty and harmony of the world” (522) through hearing the “unparalleled sweetness and sublimity [of the]… wild and ethereal” (522)—is, of course, one of the central tenets of transcendentalism. In In the Hemlocks, published by The Atlantic Monthly in 1866, and republished in 1871 in his collection of essays entitled Wake-Robin, Burroughs’s hermit thrush channels transcendentalist philosophy even more clearly.

I often hear [the hermit thrush] a long way off… I detect this sound rising pure and serene, as if a spirit from some remote height were slowly chanting a divine accompaniment. This song appeals to the sentiment of the beautiful in me, and suggests a serene religious beatitude as no other sound in nature does… “O spheral, spheral!” he seems to say; “O holy, holy! O clear away, clear away! O clear up, clear up!” interspersed with the finest trills and the most delicate preludes. It is not a proud, gorgeous strain… suggests no passion or emotion,—nothing personal,—but seems to be the voice of that calm, sweet solemnity one attains to in his best moments. It realizes a peace and a deep, solemn joy that only the finest souls may know… Listening to this strain on the lone mountain, with the full moon just rounded from the horizon, the pomp of your cities and the pride of your civilization seemed trivial and cheap. (Burroughs 1866/1871, 51)

Though Burroughs loved and observed closely many species of birds, it is the hermit thrush alone he imbues with transcendentalist meaning. The catbird, by contrast, was described as a “parodist of the woods… mischievous, bantering, half-ironical” (Burroughs 1865, 524); the chimney-swallow cried “a child’s riddle” (Ibid., 514); the bluebird sang an “amorous, vivacious warble” (Ibid., 517); and the bobolink was a “blithe, merry-hearted beau” (Ibid., 518) and a “rollicking, hilarious songster” (Ibid., 524) who later becomes “careworn and fretful,” “oscillating between anxiety for his brood and solicitude for his musical reputation” (Ibid., 526). Transcendentalist ideals are thus not ascribed to just any bird, but rather are naturally paired with the species that does, more so than any other, reward the solitary, self-reliant listener in the wilderness with a strikingly beautiful song. That the hermit thrush had already been positioned as the New World answer to the Old World nightingale gave it additional power as a transcendentalist symbol, as one the goals of the transcendentalists was to turn attention away from the “courtly muses of Europe” and towards homegrown (North) American thought (Emerson 1837).

Other nature writers echoed Burroughs’s belief in the spiritually and morally ennobling character of the song of the solitary hermit thrush. Nova Scotia-born, US-resident James Hibbert Langille (1841–1923), a minister, farmer, and self-taught ornithologist, emphasised its transformative potential. “‘Spiritual serenity,’ or a refined, poetic, religious devotion, is indeed the sentiment of the song. He whose troubled spirit cannot be soothed or comforted, or whose religious feelings cannot be awakened by this song, in twilight, must lack the full sense of hearing, or that inner sense of the soul which catches nature’s most significant voices. It is a voice which should always direct us heavenward.” (Langille 1884, 492). Massachusetts journalist, writer, and naturalist Frank Bolles (1856–1894) used explicitly Christian imagery to describe the song. “When the hermit thrush sings I feel as though the pine forest had been transformed into a cathedral, in which the power of an organ or the rich voice of a contralto singer was bringing out the essence of the mass” (Bolles 1891, 107). New England poet and naturalist Emily Tolman (active late 1800s–early 1900s) emphasized the importance of silence in giving the hermit thrush song its spiritual significance. “Then the stillness was broken by a note of surpassing sweetness, as though some master musician had touched a silver-toned flute… It was such a song as could only be learned in the peace and solitude of Nature’s inner-most sanctuary… As I listened to his ‘unworldly song,’ how far removed seemed all earth’s weakness and folly and sin! Serenity and a deep spiritual joy were expressed in every note. The wood seemed a cathedral; the song of the hermit a prayer” (Tolman 1900). French-born, New York State-resident naturalist and philosopher Stanton Davis Kirkham (1868–1944) heard the song as a moral call to action. “Stand and listen to the hermit-thrush and see if you can think idle thoughts. You must hear his message and feel the spirit of his invocation—the voice of one crying in the wilderness” (Kirkham 1908, 43).

While Parley and Nuttall had claimed that the hermit thrush—North America’s “best” singing bird”—was almost as good as Europe’s favoured singer, the nightingale, Burroughs regarded the birds of North America and Europe as equals, each specializing in a different area. Following his first trip to England in 1874, he wrote “I have little doubt our songsters excel in melody, while the European birds excel in profuseness and volubility” (Burroughs 1874/1880, 186). He countered the Buffonian notion that North American birdsong was inherently harsher than European, writing that in England he “heard many bright, animated notes, and many harsh ones, but few that were melodious.” Others took the English-American rivalry even further. The young Boston-born ornithologist Henry Davis Minot wrote, after a five-month trip to the England in 1880: “I believe I may justly say that as the birds of England are inferior to those of New England in variety, so are they, on the whole, in coloring and in song… she has none corresponding, as musicians, to our hermit thrush… To all her song birds (that I have heard)… [American birds are] equals or superiors, as well as I can judge” (Minot 1880, 562). Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919)—an avid outdoorsman, as well as the President of the United States from 1901-1909—concurred with this view, writing “though [the nightingale] is indeed a notable and admirable singer, it is an exaggeration to call it unequalled. In melody, and above all in that finer, height of melody where the chords vibrate with the touch of eternal sorrow, it cannot rank with such singers as the wood thrush and hermit thrush” (Roosevelt 1893, 66).

“Solitary, singing in the West”: The Hermit Thrush of Poetry (1865–1940s)

The hermit thrush receives passing mention in North American poetry beginning in 1840s, but the first to give hermit thrush song a prominent role was the highly influential Long Island-born poet Walt Whitman (1819–1892). In When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d, written as an elegy to Abraham Lincoln in 1865–1866, the hermit thrush is one of three recurrent motifs that accompany Whitman in his process of mourning: “Lilac and star and bird twined with the chant of my soul” (Foerster 1916, 750). Whitman’s hermit thrush here is much like Burroughs’s. It is reclusive:

In the swamp in secluded recesses,

A shy and hidden bird is warbling a song.Solitary the thrush,

The hermit withdrawn to himself, avoiding the settlements,

Sings by himself a song.

(Whitman 1866, 4)

It is a remarkable singer:

O liquid and free and tender!

O wild and loose to my soul—O wondrous singer!

(p. 11)

And the song serves as a gateway to the spiritual realm, in this case hinting at eternal life as embodied in the cycles of nature:

Passing the song of the hermit bird and the tallying song of my soul,

Victorious song, death’s outlet song, yet varying ever-altering song,

As low and wailing, yet clear the notes, rising and falling, flooding the night,

Sadly sinking and fainting, as warning and warning, and yet again bursting with joy,

Covering the earth and filling the spread of the heaven,

As that powerful psalm in the night I heard from recesses,

Passing, I leave thee lilac with heart-shaped leaves,

I leave thee there in the door-yard, blooming, returning with spring.

(p. 16)

These similar conceptions of the hermit thrush are not coincidental. Whitman and Burroughs had become close friends and hiking companions in 1864, and Burroughs eagerly shared his knowledge of the natural world with Whitman (Rothenberg 2005, 80). Writing to his friend and fellow naturalist Myron Benton in 1865, Burroughs says that Whitman was “deeply interested in what I tell him about the hermit thrush, and says he has used largely the information I have given him in one of his principle poems” (Burroughs, cited in Warren 2006, 238).

Though Whitman was greatly enthusiastic about nature, he was not a naturalist: that is to say, detailed, scientific observation of species and ecosystems was less important to him than his experience of communion with the natural world. Whitman’s interest in hermit thrush song may thus have been as much because of the symbolic meaning ascribed to it as because of any knowledge or experience of the hermit thrush itself. Whitman spent considerable time outdoors, so he is likely to have heard hermit thrushes, but whether he could reliably identify them is another question. Whitman’s lack of specificity about the hermit thrush becomes clear when looking at the successive versions of his semi-autobiographical poetic manifesto, now called Starting from Paumanok, which was first published in his ever-changing poetry collection Leaves of Grass in 1860. The hermit thrush first appears in the 1867 version, where it plays a prophetic role, setting the direction for Whitman’s poetic and personal life journey.

And heard at dusk the unrivall’d one, the hermit thrush from the swamp-cedars,

Solitary, singing in the West, I strike up for a New World.

(Whitman 1867)

Yet in the earlier version of this same poem, Proto-leaf (1860), the mockingbird—a bird with entirely different habits and song structure—had served this same purpose.

Aware of the mocking-bird of the wilds at day-break,

Solitary, singing in the west, I strike up for a new world.

(Whitman 1860)

Whitman thus seems to have had a poetic image in mind which he then sought to populate with the most appropriate species he could think of, rather than to be writing about any actual experience he had had with a particular bird. Even once he hit upon the ideal bird to fit his poetic needs, he continued to refine his imagery. By the 1881 version of Starting from Paumanok, his hermit thrush was “heard at dawn” rather than at dusk, perhaps to better symbolize the idea of striking out for a new beginning (Whitman 1881).

Following the publication of Whitman’s two poems, hermit thrush song became an increasingly popular poetic topic throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Though not all poets who wrote about hermit thrush song would have identified as transcendentalists, the transcendentalism-inspired conception of the hermit thrush as a solitary, exceptional, and otherworldly singer had become so embedded in public consciousness that almost all poems of this era reflect this imagery. To give just a few examples, Alabama poet and composer Julia Zitella Cocke (1840–1929) painted the hermit thrush as a hermit in the religious sense in The Hermit Thrush.

A hermit he, from the world hiding;

Like anchorite,

In solitude of the Thebaid;—

With morning light

Intones his matins, and his vespers

At fall of Night!

(Cocke 1895, 48)

East Coast-born, California-resident resident lawyer and poet John Vance Cheney (1848–1922) echoes not only Burroughs imagery, but also his verbal transcription of hermit thrush song (“holy, holy”) in his quatrain, also called The Hermit Thrush, which posits hermit thrush song as a prayer.

Holy, Holy! – In the hush

Hearken to the hermit-thrush;

All the air

Is in prayer.

(Cheney 1902, 53)

Emily Tolman, whose writing as a naturalist is discussed above, includes both Burroughs’s words and Whitman’s imagery—“star and bird twined”—in her The Hermit Thrush.

Holy ! oh — holy, holy!

Again at evening dusk, now near, now far, —

Oh, tell me, art. thou voice of bird or star?

(Tolman 1901)

The similarity of imagery in all of these poems suggests that poets may have been primarily interested in situating themselves within a tradition of writing about the hermit thrush, rather than reflecting directly on any personal experience with a hermit thrush. Or perhaps the transcendentalism-inspired imagery surrounding the hermit thrush had become so pervasive that it had become impossible to interpret the experience through any other lens.

Though transcendentalism started as an American movement, the personal and intellectual connections between poets and thinkers in the US and Canada (and previously the Province of Canada), and the geographical proximity of the two countries, mean that values and imagery were often shared across borders. New Brunswick-born poet, novelist, and essayist Charles G. D. Roberts—considered a “Confederation Poet” because belonged to the generation of poets born during Canadian confederation—heard hermit thrush song as a conduit to religious experience in his The Hermit Thrush.

O cloistral ecstatic! thy cell

In the cool green aisles of the leaves

Is the shrine of a power by whose spell

Whoso hears aspires and believes!

O hermit of evening! thine hour

Is the sacrament of desire,

When love hath a heavenlier flower,

And passion a holier fire!

Oh, clear in the sphere of the air,

Clear, clear, tender and far,

Our aspiration of prayer

Unto eve’s clear star!

(Roberts 1892/1985, pp. 143–144)

Roberts’s line “clear in the sphere of the air” likely makes reference to Burroughs’s onomatopoeic rendering of hermit thrush song as “O spheral, spheral!” Roberts and Burroughs were certainly familiar with each other’s writing, though Burroughs was later to become a critic of what he considered to be excessive sentimentality in Roberts’s nature writing (Burroughs 1903). Bliss Carman, also a Confederation Poet, and a cousin to both Roberts and Emerson, likewise grew up in New Brunswick, though spent much of his adult life in New England. He describes the hermit thrush as a priest, in his poem Wild Garden.

For what is the sacrament sense receives,

When the new moon hangs in the purple pine

And silence speaks and the heart believes,

But a portal that leads to the inner shrine?

And our hermit thrush at his evening psalm

Is celebrant of that holy calm.

(Carman 1929, 75)

The above-mentioned poems barely scratch the surface of North American hermit thrush-related verse. A search of English-language newspapers, magazines, and books published between 1811, the year of the first contemporary usage of the term “hermit thrush,” and the present, reveals no less than 128 poems written expressly about the hermit thrush, or with a substantial passage about hermit thrush song, with the majority (97) of them written between 1865 and 1940. (Numerous other poems mention the hermit thrush in passing, but these are not discussed here).

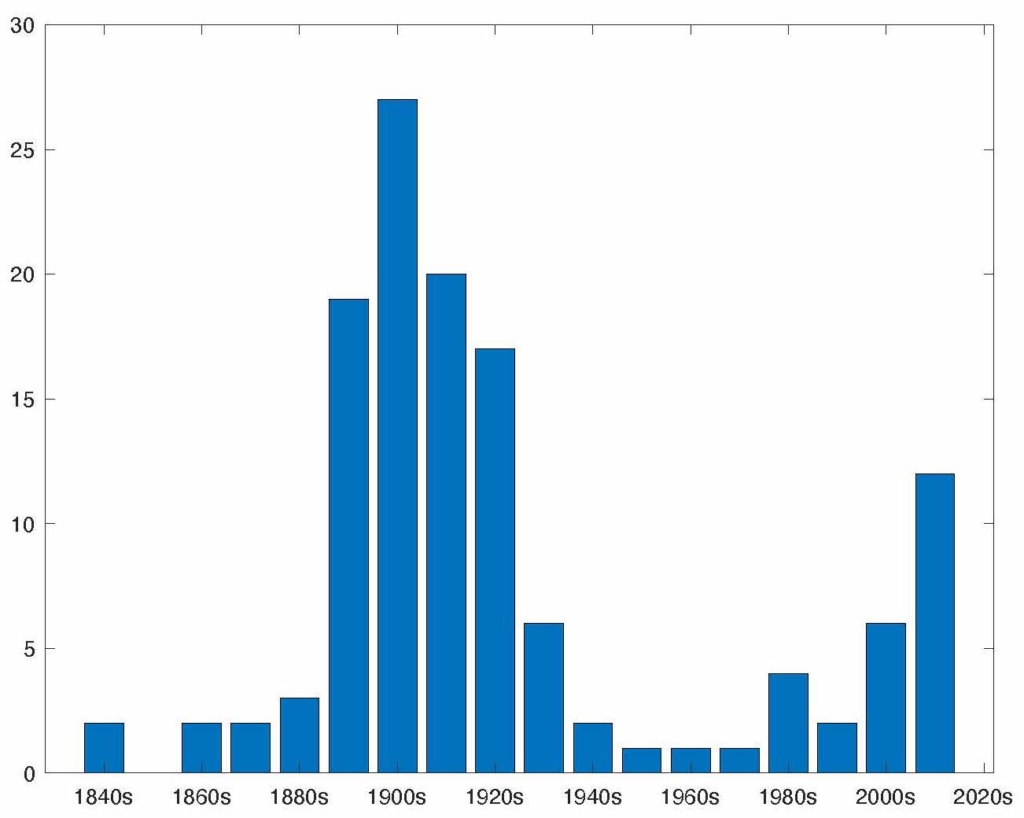

Figure 2. Number of poems written per decade which are wholly or partially about hermit thrush song. Poems were found by searching Google Books, Google Scholar, Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Nineteenth Century Collections Online, The Nineteenth Century Index, Project Gutenberg, Hathi Trust, Archive, Poetry Explorer, Poem Hunter, Poetry Archive, Poets.org, Canadian Poetry, American Poetry, 20th Century American Poetry, Newspapers.com, Bavarian State Library, Proquest, American Periodicals, and Gale Primary Sources.

Though more recent poems are somewhat more diverse in concept and content, the poems written between 1865 and 1940 reinforce, with few exceptions, the image of the hermit thrush as the admirably solitary, spiritually and morally upstanding, and aesthetically refined embodiment of a transcendentalism-influenced North American ideal. Though an analysis of each of these poems individually is beyond the scope of this essay, a rudimentary analysis of word usage in the corpus of late 19th and early 20th century hermit thrush-related poetry (including the entirety of poems exclusively about the hermit thrush, and the hermit thrush-related passages of poems partially about the hermit thrush) shows the predominance of this imagery. In these 128 poems there are 427 occurrences of words related to the solitary nature of the hermit thrush (e.g. solitude, solitary, alone, lone, lonely, still, stillness, etc.), 571 words related to its musicality (e.g. song, tune, melody, flute, flutelike, music, musics, minstrel, etc.), and 316 related to its religiosity (e.g. spirit, angel, divine, holy, prayer, etc.). Other words that one might expect to be equally associated with hermit thrush song occur much less frequently: for example, there are only 109 references to the hermit thrush’s woodland habitat (e.g. wood, woodland, forest, trees, etc.).

The hermit thrush in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, published in 1922 (in The Criterion in the UK and in The Dial in the US), initially appears to be an exception to the transcendentalism-inspired representation of the hermit thrush era.

Where the hermit-thrush sings in the pine trees

Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop

But there is no water

(Eliot 1922, 43)

Though none of the usual hermit thrush imagery is used (unless we read “pine trees” as alluding to an isolated woodland setting), Eliot makes it clear that he was well aware of the symbolism typically associated with the bird. In his notes on The Waste Land, he writes: “This is Turdus aonalaschkae pallasii, the hermit-thrush which I have heard in Quebec Province. Chapman says (Handbook of Birds of Eastern North America) ‘it is most at home in secluded woodland and thickety retreats…. Its notes are not remarkable for variety or volume, but in purity and sweetness of tone and exquisite modulation they are unequalled” (Eliot 1922, 61). Eliot’s claim that the hermit thrush’s “‘water-dripping song’ is justly celebrated” is more puzzling: he was an experienced amateur birder, and would have known the bird had no such song (Irmscher 2014, 242). Literary scholar Christoph Irmscher suggests that Eliot intentionally misrepresents hermit thrush song to emphasize the unbearable aridity of The Waste Land. “If the hermit thrush, in the literary and ornithological tradition, pours forth showers of song, in Eliot it dribbles like a leaky faucet until that sound stops, too… In a world where hermit thrushes do not chant or call but drip and drop and then not even that, revelation of any kind is as uncertain as the prospect of rain which, after all that dryness, might or might not come” (Irmscher 2014, 246).

“Folly to Attempt a Description”: Musical Transcriptions of Hermit Thrush Song (1890s-1950s)

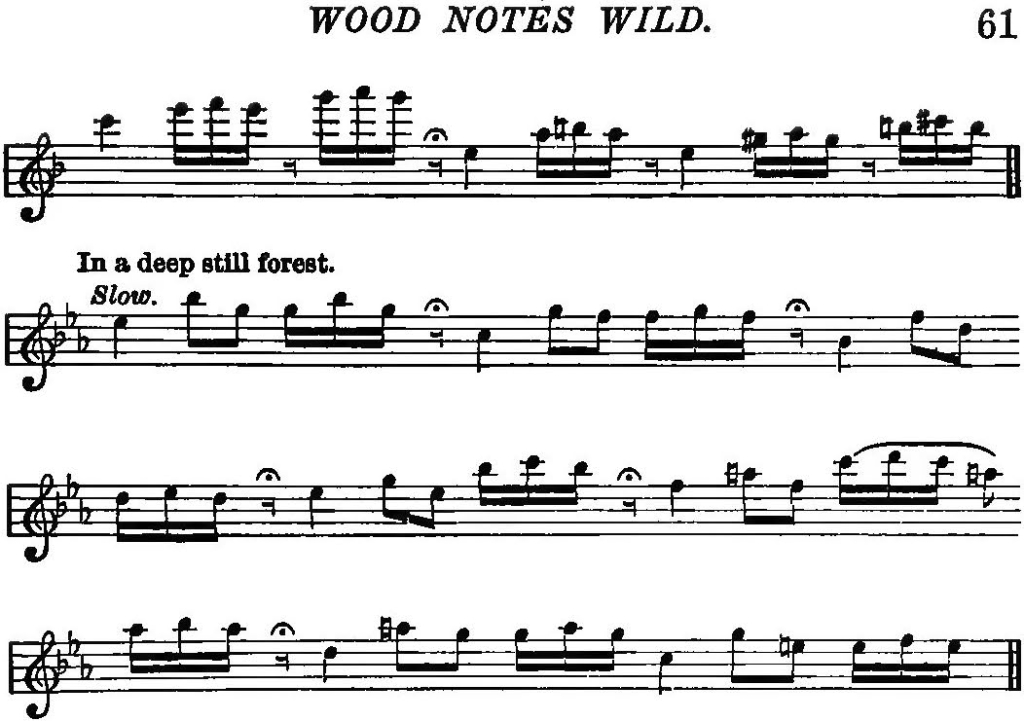

For a bird whose song was so often described in musical terms, hermit thrush song itself is surprisingly absent from late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century music (with one notable exception, to be discussed below). However, naturalists recognized that it was “folly to attempt a description of the music of the thrushes” through words alone, and often supplemented their verbal descriptions of hermit thrush song with musical notation (Cheney 1892, 60). This practice reached its peak popularity between from the late nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century (for further reading on the history of musical transcription of bird song, see Mundy 2018).

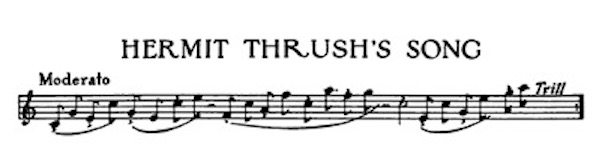

Example 1. Notations of hermit thrush song in (top) Simon Pease Cheney’s Wood Notes Wild (Cheney 1892, 61), and (bottom) Alida Chanler’s Environment and the Songs of Birds in The New Country Life (Chanler 1917, 73).

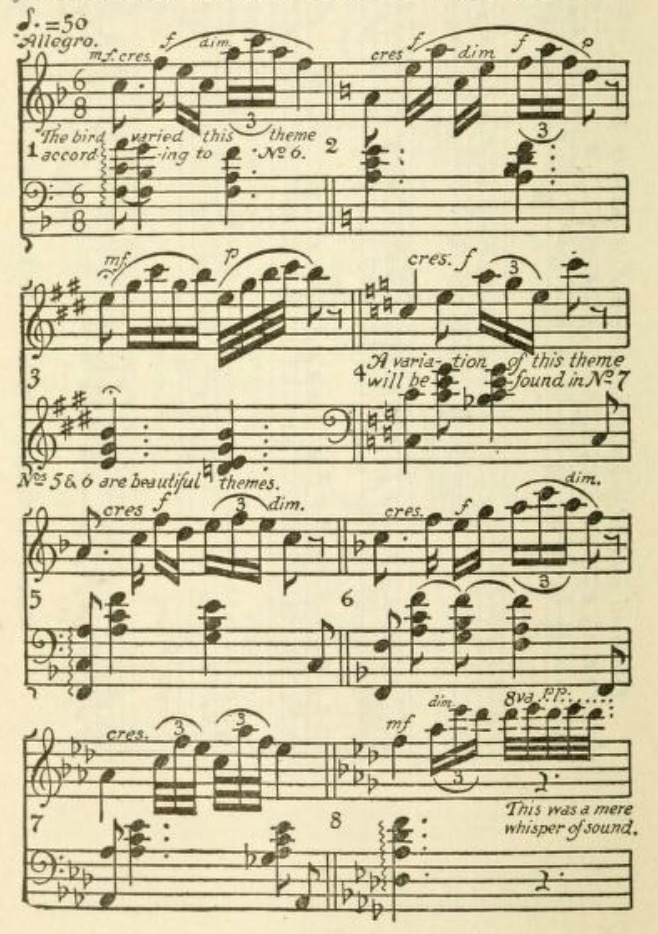

In some cases, these naturalists even wrote chordal accompaniments for their transcriptions, but these accompanied birdsongs were “intended to assist in the identification of species common in the United States East of the Rocky Mountains” themselves rather than as stand-alone compositions (Mathews 1904, title page).

Example 2. Accompanied transcription of a hermit thrush song in F. Schuyler Mathews’s Field Guide to Wild Birds and Their Music (Mathews 1904, 260). (Though Mathews here interpreted hermit thrush song as being based in the major and minor keys of Western Classical music (p. 261), by the time of the 1921 revision of Field Guide, he had become convinced that it was based on the “pentatonic scale.” For further discussion of this problematic turn, see Doolittle 2020).

“Bird impersonators” such as Charles Gorst and Edward Avis performed whistled renditions of birdsongs, including that of the hermit thrush, but did so in educational or novelty contexts, rather than as independent pieces of music (“Charles Gorst Celebrated” 1919, 1).

Figure 3. “Bird impersonator” Charles Gorst’s whistling range as represented in his promotional material (Gorst 1920–1929, 3). Although Gorst is known to have imitated the hermit thrush, that recording is not available: this is a recording of some of his other bird imitations.

A few composers from late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—among them Winthrop Rogers, Albert Mack, Frederick Shepherd Converse, Thaddeus Giddings, and Charles Daley—wrote settings of hermit thrush-inspired poetry, including that by Whitman, Tolman, and Kathleen Millay (sister to Edna St Vincent Millay), but the extant settings show little or no influence from hermit thrush song itself. It seems that these composers were more attracted to the poetry, or to the hermit thrush as a symbol, than to the song. This contrasts with the treatment of birdsong in European music of the same era, in which the songs and calls of nightingales, larks, cuckoos, and other favoured birds make frequent appearances, albeit in highly stylized form. A few examples would be Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, “The Pastoral,” which features quail, cuckoo, and nightingale imitations; Saint-Säens’s Carnival of the Animals (1886), which includes imitations of chickens and cuckoos, as well as imitations of animal motion (Martinelli 2008, 132); Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 (1888), which includes a cuckoo imitation, singing a perfect 4th rather than the usual major or minor 3rd, but recognizable nonetheless by its rhythm and contour; Ralph Vaughan-Williams Lark Ascending (1914), in which the violin roughly imitates the trilling of a lark’s song; Ottorino Respighi’s Pines of Rome (1924), which incorporates a recording of a nightingale; as well as some more generalized imitations of bird choruses in pieces such as Bederich Smetana’s Z českých luhů a hájů (“From Bohemian Woods and Fields,” 1875) and Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1913) (Doolittle 2008; Mâche 1992, 121).

“A Hermit Thrush at Morn” and “A Hermit Thrush at Eve”: Amy Beach and the Hermit Thrush in Music (1922)

Amy Beach’s pair of piano pieces, A Hermit Thrush at Morn and A Hermit Thrush at Eve, published in 1922, stand alone in their faithful representation of hermit thrush song in a purely musical (rather than educational or novelty) context. The Boston-born Beach (1867–1944) had cultivated since childhood a practice of transcribing birdsong: as someone with perfect pitch, an unusual ability to concentrate, and a great love of nature (including a preference for composing outdoors), she was especially well equipped to do so with a high degree of detail and precision (Von Glahn 2013, 32–47). Beach accurately represents the rhythmic structure, pitch relationships, and pacing of hermit thrush song, including its frequent use of intervals from the harmonic series, and sets it against a more traditional accompanimental figures in her pair of contrasting but complementary pieces. Beach notes on the bottom of the score that “these birdcalls are exact notations of hermit thrush songs, in the original keys but an octave lower, obtained at MacDowell Colony, Peterborough, N.H.,” where she had spent the summer as artist-in-residence for the first time in 1921. Indeed, the hermit thrush came to symbolize the MacDowell Colony for Beach: when she tried to help raise funds for MacDowell following a destructive storm in 1938, she solicited contributions in the name of the hermit thrush (Block 1998, 286).

Though music based on naturalistic (rather than highly stylized) transcriptions of birdsong was to become common later in the century (beginning with Olivier Messiaen’s intensive use of birdsongs from the 1940s onwards), the birdlike nature of Beach’s pieces was unusual in its day (Von Glahn 2011, 402).[2] Beach was interested not only in the sound of hermit thrush song, but also in its cultural symbolism (Von Glahn 2011, 402). At the top of each piece Beach includes a passage of thrush-related verse. Hermit Thrush at Morn was paired with John Vance Cheney’s quatrain (discussed above), and Hermit Thrush at Eve was paired with a few lines from English poet John Clare (1793-1864), who presumably refers here to an English-native bird such as the song or mistle thrush, but does so in terms general enough to apply across thrush species:

I heard from morn to morn a merry thrush

Sing hymns of rapture, while I drank the sound

With joy.

(Clare 1835, 128)

In this sense, Beach’s work can be seen as parallel to Burroughs’s, in that she seeks to bring the poetic and the scientific together to create the fullest way of understanding and experiencing hermit thrush song. Ecomusicologist Denise Von Glahn describes Beach’s balancing of these two worldviews thus:

While Beach embraced a religio-romantic nature ideology on the one hand, the pair of hermit thrush pieces shows the composer balancing two paradigms of nature. At the same time that Beach held fast to many aspects of a God-imbued nature ideology, and by so doing continued to champion one aspect of the nation’s presumed exceptionalism, she also moved beyond a pre-Darwinian reading of the natural world. The importance that Beach attached to her transcription of the hermit thrush song suggests different thinking, that which was privileged later in the century and especially among those scientifically inclined ornithologists and botanists who prided themselves on their accurate observation and precise description of natural phenomena. (Von Glahn 2014, 43)

“Short notes in repetitive arrangement”: modern scientific writing about the hermit thrush (1940s-present)

By the mid-twentieth century, interest in hermit thrush song had begun to wane. Of course no one wrote about why they were no longer writing about the hermit thrush, but several factors may have come into play. Primary among these would have been the development of recording technology. Though the first recording of a bird in a zoo had been made in 1889, recording equipment was noisy and cumbersome throughout the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, making field recording difficult. As technology improved, recording wild birds became increasingly feasible, and by the 1930s, birdsong recordings were available for both scientists and the general public. Hermit thrush song first appeared commercially on ornithologist Albert Brand’s recording Native Bird Song, released by the Laboratory of Ornithology at Cornell University in 1938. People—whether coming from a scientific or an artistic point of view—thus no longer needed to describe birdsongs in detail to remember them or discuss them with others, as they could simply use a recording. Sound spectrograms, initially developed as military technology during the 1940s, were used for creating visual representations of birdsong beginning in the 1950s, further reducing the perceived need for verbal or musical transcriptions. Ornithologists could now aspire to “describe the sound patterns of animals objectively” (Stein 1956, 501), rather than relying on the anecdotal and experiential reports of previous generations. Whereas there had previously been frequent overlap between naturalistic, ornithological, and poetic accounts of hermit thrush, modern scientific descriptions of the song as “short notes in a repetitive arrangement” (Stein 1956, 510) or similar perhaps provided less fodder for the poetic imagination (see Taylor 2017, 37, for further discussion of the limitations of objective description).

The experience of hearing hermit thrush song was thus no longer inherently connected with wilderness settings: one could now listen to a hermit thrush anywhere there was a gramophone. Simultaneously, North America was urbanizing, so fewer people would ever have had the opportunity to hear the hermit thrush in the wilderness. Whereas 80% of the American population lived in rural areas in 1860, by 1950 only 36% did (Our World in Data 2020): the Canadian rural population dropped from 84% to 38% during the same time period (Statistics Canada 2016). North America came to be symbolized as much by monuments to modernity and progress—the Empire State Building, built in 1931, for example—as by references to vast expanses of wilderness and the creatures that can to be found there (King 2004, 11–12).

Conclusion

Of course interest in the hermit thrush did not disappear entirely: a trickle of writing about the hermit thrush continued throughout the mid-twentieth century. The 1970s, with its focus on environmentalism, brought with it a resurgence of attention to hermit thrush song among poets, naturalists, scientists, and most especially among composers. Whereas there were three compositions which include imitations of hermit thrush song written between 1920 and 1970, including Beach’s pair of piano pieces, a probable reference to hermit thrush song in Bela Bartok’s 1945 Third Piano Concerto (Harley 1994, 11–12), and a definite transcription of hermit thrush song in Olivier Messiaen’s 1956 Oiseaux Exotiques, there are at least forty-eight such pieces written between 1970 and 2020. These range from direct transcriptions of the song, as in Daniel Goode’s series of hermit thrush pieces (1974–present) and my piece Utah, 1996 (2009), to pieces which respond to the hermit thrush, such as Elizabeth Brown’s Hermit Thrush (1991), to those which use it as a symbol, such as Kate Moore’s The Hermit Thrush and the Astronaut (2012). At least eight of the composers who have used hermit thrush song in their music since the 1970s—Eleanor Aversa, Diane Moser, William Schuman, Roger Sessions, Arlene Sierra, Brown, Moore, and myself—have, like Amy Beach, a connection to MacDowell, and in some cases were inspired directly by hearing a hermit thrush there.

Small vestiges of the hermit thrush’s symbolic resonance remain: it is the State Bird of Vermont, the name of a Vermont-based brewery, the name of a Canadian band. But the hermit thrush no longer serves as a widespread symbol of North American cultural identity, it is just a bird, albeit a reclusive bird with an interesting song, an interesting history as a symbol of English-speaking Canadian and American identity, and a fascinating body of works in all genres surrounding this history.

Notes

[1] In fairness to Buffon, by the racist standards of his time, he was considered anti-racist, because he argued against those who thought different “races” were different species, and believed that given the “right” (i.e. European) conditions, people of all races had the same potential. For further reading on how racist ideologies have informed discussion of animal song, see Animal Musicalities by Rachel Mundy (2018).

[2] Fannie Charles Dillon, a fellow MacDowell resident and friend of Beach’s also wrote pieces based on bird transcriptions, but few of her pieces survive (Block 1998, 222).

References

Allen, Aaron S. 2011. “Ecomusicology: Ecocriticism and Musicology.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 64 (2): 391–394.

Allen, Aaron S., and Kevin Dawe. 2016. “Ecomusicologies.” In Current Directions in Ecomusicology: Music, Nature, Environment, edited by Aaron S. Allen and Kevin Dawe, 1–15. London: Routledge.

Audubon, John James, and William MacGillivray. 1839. The Birds of America: From Drawings Made In the United States And Their Territories. Vol. 3. New York: George R. Lockwood.

Bangs, Outram, and Thomas E. Penard. 1921. “The Name of the Eastern Hermit Thrush.” The Auk 38 (3): 432–434.

Bentley, David M. R. 2004. The Confederation Group of Canadian Poets, 1880–1897. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Block, Adrienne Fried. 1998. Amy Beach, Passionate Victorian: The Life and Work of an American Composer 1867–1944. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bolles, Frank. 1891. In the Land of Lingering Snow: Chronicles of a Stroller in New England from January to June. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Buckley, Michael G. 2010. “Toward an Elevating Picturesque: Wilson Flagg and the Popularization of the Nature Essay.” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 17 (3): 526-540.

Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de. 1792. The Natural History Of Birds From The French Of The Count De Buffon. London: A. Strahan, and T. Cadell.

Burroughs, John. 1865. “With the Birds.” The Atlantic Monthly 15, 513–528.

Burroughs, John. 1866. “In the Hemlocks.” Originally published in The Atlantic Monthly. Boston: Moses Dresser Phillips. Republished in Wake-Robin, 1871, 39–74. New York: Hurd and Houghton.

Burroughs, John. 1874. “Mellow England.” Originally published in Scribner’s Monthly. New York: Scribner and Company. Republished in Winter Sunshine, 1880, 151–189. Boston: Houghton, Osgood and company.

Burroughs, John. 1903. “Real and Sham Natural History.” The Atlantic Monthly 91.

Carman, William Bliss. 1929. “The Hermit Thrush.” In Wild Garden, 74–76. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company.

Chanler, Alida Beekman. 1917. “Environment and the Songs of Birds.” The New Country Life 31 (6): 71–73.

“Charles Gorst Celebrated Bird Man on the Lyceum Platform.” 1919. The Crescent (Pacific College, Newburg, OR) 30 (4), February 4: 1.

Cheney, Simon Pease. 1892. Wood Notes Wild. Boston: Lee and Shepard Publishers.

Cheney, John Vance. 1902. “The Hermit Thrush.” Everyday Housekeeping 17 (2): 53.

Clare, John. 1835. “The Thrush’s Nest.” The Rural Muse. London: Whitaker and Company, 128.

Cocke, Julia Zitella. 1895. “The Hermit Thrush.” A Doric Reed. Boston: Copeland and Day.

Connor, Wiliam. 1997. “Canadian Essay.” In Encyclopedia of the Essay, edited by Tracy Chevalier, 302–310. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers.

Coues, Elliott. 1878. Birds of the Colorado Valley: a Repository of Scientific and Popular Information Concerning North American Ornithology. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Creece, Mary R. S., and Thomas M. Creece. 2010. Ladies in the Laboratory II: South African, Australian, New Zealand, and Canadian Women in Science: Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press.

Del Hoyo, Josep, Andrew Elliott, David Christie, and Simon Aspinall. 2005. Handbook Of The Birds Of The World. Barcelona: Lynx.

Doolittle, Emily. 2008. “Crickets in the Concert Hall: A History of Animals in Western Music.” Trans Revista Transcultural de Música 12. Issn: 1697-0101.

Doolittle, Emily. 2020. “‘Hearken to the Hermit Thrush‘: A Case Study in Interdiciplinary Listening.” Frontiers in Psychology 11 (December 09).

Doolittle, Emily, Bruno Gingras, Dominik Endres, and W. Tecumseh Fitch. 2014. “Overtone-based pitch selection in hermit thrush song: Unexpected convergence with scale construction in human music.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (46): 16616-16621. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1406023111

Dugatkin, Lee Alan. 2019. “Buffon, Jefferson and the Theory of New World Degeneracy.” Evolution: Education and Outreach 12 (15). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-019-0107-0

Dyck, Jeff, recordist. XC379755. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/379755 .

Eliot, Thomas Stearns. 1922. The Waste Land. New York: Horace Liveright.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. 1837. The American Scholar. Available at https://emersoncentral.com/texts/nature-addresses-lectures/addresses/the-american-scholar/ .

Fadden, John Kahiones. 2020. Mohawk Nation. Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center. Personal Communication.

Foerster, Norman. 1916. “Whitman as a Poet of Nature.” Publications of the Modern Language Association 31 (4), 736–758.

Glazener, Nancy. 1997. Reading for Realism: The History of a U. S. Literary Institution 1850–1910. London: Duke University Press.

Gorst, Charles Crawford. 1920-1929. The Bird Man [pamphlet]. Available at http://128.255.22.135/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tc/id/40463/rec/43 .

Harley, Maria Anna (Maja Trochimczyk). 1994. “Birds in Concert: North American Birdsong in Bartók’s Piano Concerto No. 3.” Tempo, New Series 189: 8-16.

Hooker, William Jackson. 1840. Flora Boreali-Americana. London: Henry G. Bohn.

Irmscher, Cristoph. 2014. “Listening to Eliot’s Thrush.” Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas 12 (2): 231–249.

King, Anthony. 2004. Spaces of Global Cultures: Architecture, Urbanism, Identity. New York: Taylor and Francis.

Kirkham, Stanton Davis. 1908. In The Open: Intimate Studies And Appreciations Of Nature. New York: Paul Elder and Company.

Kroodsma, Donald. 2005. The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Lane, Richard J. 2011. The Routledge Concise History of Canadian Literature. London: Routledge.

Langille, James Hibbert. 1884. Our Birds in Their Haunts: A Popular Treatise on the Birds of Eastern North America. Boston: S. E. Cassino.

Lawrence, Elizabeth Atwood. 1997. Hunting The Wren. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Von Linné, Carl (Carl Linnaeus), and Johann Georg Gmelin, J. F. 1788. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tom I pars II. Leipzig: Georg Emanuel Beer.

Lupfer, Eric. 2010. “Becoming America’s ‘Prophet of Outdoordom’: John Burroughs and the Profession of Nature Writing, 1856–1880.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 52 (4): 381-407.

Mâche, François-Bernard. 1992. Music, Myth, and Nature, or, The Dolphins of Arion. Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Martinelli, Dario. 2008. Of Birds, Whales, and Other Musicians. Chicago: University of Scranton Press.

Mathews, Ferdinand Schuyler. 1904. Field Book of Wild Birds and Their Music. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

McPherson, Christopher, recordist. 2020. Hermit thrush recording XC601486. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/601486 .

Minot, Henry Davis. 1880. “English Birds Compared with American.” The American Naturalist 14 (8): 561–565.

Mundy, Rachel. 2018. Animal Musicalities. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Nuttall, Thomas. 1840. A Manual of the Ornithology of the United States and of Canada, The Land Birds: Second Edition with Additions. Boston: Freeman and Bolles.

Oneida Indian Nation. 2020. The Legend Of The Hermit Thrush [online]. Available at https://www.oneidaindiannation.com/the-legend-of-the-hermit-thrush/ .

Ord, George. 1828. Sketch Of The Life Of Alexander Wilson, Author Of The American Ornithology. Philadelphia: Harrison Hall.

Otis, Melissa. 2018. Rural Indigenousness: A History of Iroquoian and Algonquian Peoples of the Adirondacks. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Our World in Data. 2020. Available at https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/urban-and-rural-populations-in-the-united-states .

Perceval, Anne Marie. 1825. Letter to William Hooker, in Director’s Correspondence (Kew Gardens), DC 44 (117) (October 23).

Powers, Mabel. 1917. Stories the Iroquois Tell Their Children. New York: American Book Company.

Roach, Sean. P., Lynn Johnson, and Leslie S. Phillmore. 2012. “Repertoire Composition and Singing Behaviour in Two Eastern Populations of the Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus).” Bioacoustics 21: 239–252. doi: 10.1080/09524622.2012.699254.

Roberts, Charles G. D. 1985. The Collected Poems of Sir Charles G.D. Roberts, edited by Desmond Pacey. Wolfville, NS: Wombat Press.

Rothenberg, David. 2005. Why Birds Sing. New York: Basic Books.

Roosevelt, Theodore. 1893. The Wilderness Hunter. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Sheppard, Harriet. 1833. “Notes on Some of the Canadian Song Birds.” Transactions of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, vol. II. Quebec: W. Neilson. Reprinted 1927. Quebec: The Chronicle-Telegraph Publishing Show Ltd.

Shippey, Thomas Alan. 1970. “Listening to the Nightingale.” Comparative Literature 22 (1): 46–60.

Shteir, Ann, and Jacques Cayouette. 2019. “Collecting with ‘Botanical Friends’: Four Women in Colonial Quebec and Newfoundland.” Scientia Canadensis 41 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.7202/1056314ar.

Snider, Alvin. 1997. “Nature Essay.” In Encyclopedia of the Essay, edited by Tracy Chevalier, 1254–1256. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers.

Statistics Canada. 2016. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/91-003-x/2014001/c-g/desc/desc04-eng.htm .

Stein, Robert Carrington. 1956. “A Comparative Study of ‘Advertising Song’ in the Hylocichla Thrushes.” The Auk 73 (40): 503–512.

Taylor, Hollis. 2017. Is Birdsong Music? Outback Encounters with an Australian Songbird. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Tehanetorens. 1993. The Sacred Song of the Hermit Thrush. Summertown, TN: Book Publishing Company.

Tolman, Emily. 1900. “The Haunt of the Hermit Thrush.” Congregationalist 85 (July 26): 111.

Tolman, Emily. 1901. The Hermit Thrush. The Independent 53 (July 25): 1729.

Van Dyke, Henry. 1980. The Hermit Thrush. Available at http://www.bookrags.com/ebooks/16229/16.html#gsc.tab=0 .

Von Glahn, Denise. 2014. Music and the Skillful Listener. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Von Glahn, Denise. 2011. “American Women and the Nature of Identity.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 64 (2): 399–403.

Warren, James Perrin. 2006. John Burroughs and the Place of Nature. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Webster, Richard E, recordist. XC351970. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/351970 .

Webster, Richard E, recordist. XC612892. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/612892 .

Whitman, Walt. 1866. Proto-Leaf. Available at https://whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1860/poems/1 .

Whitman, Walt. 1866. “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” In Memories of President Lincoln, 3–12. New York: Little Leather Library Corporation.

Whitman, Walt. 1867. Starting from Paumanok. Available at https://whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1867/poems/2 .

Whitman, Walt. 1881. Starting from Paumanok. Available at https://whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1881/poems/26 .

Wilson, Alexander, and Charles Lucian Bonaparte. 1831. American Ornithology or the Natural History of Birds of the United States, volume II. Edinburgh: Constable & Co.

Wistrand, Matt, recordist. Hermit Thrush Recording XC653780. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/653780 .