by Olusegun Stephen Titus

Abstract

Like many genres of song, nature songs contain philosophical principles which can be derived for human learning. This paper examines natural elements as socio-cultural signifiers in a selected song by Christopher Omotoso. One of his songs contains bird metaphors that re-enact the socio-cultural philosophies of the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria. This paper therefore examines how one of his musical pieces, “Eye Orofo” (a type of parrot), is enriched by natural phenomena and how he mobilizes and explores these elements. Data were collected through interviews, cultural history, and participant observation during the performance of the song. The song was analyzed using insights from ecomusicological theory. This paper suggests that songs reflect larger environmental tensions within Yoruba culture. It suggests that the musical representation and signification of nature in “Eye Orofo” reflects on the socio-cultural, signifying cautions, moderations, abilities, inadequacies, and the need for good interpersonal relations within the Yoruba worldview.

Introduction

Bird elements have been used in songs from time immemorial. Among the Yoruba people, birds are rich in socio-cultural significance. While several studies have been done on Yoruba music (Vidal 2016; Omojola 2006; Olaosun 2016, among others), no study has been done on how bird metaphors signify Yoruba cultural values and concerns, including moderations, abilities, cautions, inadequacies, virtues and environmental sustainability. This paper examines how musical discourse in Nigeria is enriched by natural phenomena, particularly as mobilized and explored in Christopher Omotoso’s song. It suggests that the musical representation and signification of birds in the song texts of Christopher Omotoso expresses and promotes human caution, moderation, contentment, abilities, aspirations, inadequacies, good interpersonal relations, and respect for others and the environment.

This paper answers the following questions: how are ecomusicological ideals of nature represented in Christopher Omotoso’s “Eye Orofo” song? What is the significance and role of birdsong in “Eye Orofo?” In the course of research for this paper, I conducted interviews to solicit people’s opinions, perceptions, and reception of Christopher Omotoso’s song. I sourced representations and significations of nature elements in the song, and carried out participant observation during rehearsals and performances of the song. The musical score was sourced from the composer. I recorded the song during the concert organized by the composer. The song was played several times and manually translated to the English language. I then analyzed the text based on ecomusicological theory. Ecomusicological theory informs this study because it emphasizes the triangulation of culture, environment and human beings (Allen, Titon, and Von Glahn 2014). In this paper, I consider ecomusicology not only in the context of music about the environment, but to examine the engagement of non-humans as signifiers of the environmental degradation experienced among the Yoruba people.

“The lost African Grey Parrot (Psittacus erithacus erithacus)” by Another Seb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Overview of Ecomusicology as a Discipline

Numerous studies on the relationship between birds and music have been carried out (for example, Feld 1991; Urquhart 2004; Rothenberg 2005; Baptista and Keister 2005; Doolittle 2007). Taylor (2011) argues that birds have been muses to composers through the ages, but that birdsong can provide more than inspiration to composers. The current paper extends this assertion, not merely examining the composer’s inspiration but focusing on the socio-cultural signification of moderation and respect for the environment. Silver (2015, 394) notes that Luiz Gonzaga’s musical work references the songs of birds in migratory flight and in cages. He further opines that Gonzaga’s songs reference birdsong by describing the meaning of the bird call in relation to the arrival of rain or drought in Northeastern Brazil. Silvers explains that the purple-throated euphonia’s call heralds rain, while the laughing falcon’s call heralds drought. This paper deviates from Silvers’s approach, which analyzes how birdsong forecasts the rain and drought which lead to bountiful agricultural harvest or lack of it. Instead, I examine how Christopher Omotoso’s birdsong signifies the need for human caution and environmental sustainability.

Taylor and Hurley (2015) echo the interaction between music and the environment, noting that it potentially brings about social stability. This is also true with Christopher Omotoso’s birdsong. Guy’s research into Taiwanese popular music notes that the texts reference natural phenomena and named places, especially waterways and, in particular, the Tamsui River (Guy 2009, 223). She analyzes the musical representation of the once vital and now toxic river that has captured the imagination of songwriters for decades. Through the lyrics of songs about the Tamsui River, Guy performs a “green reading” of popular music in Taiwan. Furthermore, she elucidates how the songs inform us about a Taiwanese environmental imagination. Christopher Omotoso’s birdsong enacts the consciousness of environmental sustainability through human responsibility.

Rees (2016) examines ecological songs written in the wake of modernization in China. In her landmark research on popular music and the mediation of traditional ecological knowledge, Rees elucidates the sudden Chinese receptivity to ecological songs. Her study references a wealth of current concerns over the environment, social change, and disappearing traditional arts, tapping into a sense of nostalgia for a more locally rooted past. This paper examines how Christopher Omotoso’s birdsong reminds listeners of the environmental sustainability that existed in the past, and how the lack of moderation has led to human encroachment on nature and brought environmental degradation. In examining the approach that ecomusicology should take, Rehding (2011) enumerates apocalyptic and nostalgic approaches. He argues that since the literary arts have mostly focused on an apocalyptic approach, ecomusicology should rather appeal to a nostalgic move of love. He further notes that:

Many in the narrative arts have taken the attention-grabbing apocalyptic route to raise awareness by instilling a sense of acute crisis in its audiences. It is quite possible that the most productive way forward for ecomusicology will be to follow the alternative route (414).

Christopher Omotoso’s birdsong in this paper utilizes both apocalyptic and nostalgic approaches, due to the devastating effects of environmental degradation that his song epitomizes.

Yoruba Usage of Animal Metaphors in Poems and Songs

The Yoruba constitute the second-largest ethnic group in Nigeria, the first being the Hausa/Fulani people. Yoruba are mainly found in densely forested areas, from the Gulf of Guinea to the fringes of the Niger River. The greatest concentration of Yoruba people is in the West African coast area, from where they are believed to have migrated to other countries. The majority of the Yoruba occupy southwestern Nigeria. Prominent Yoruba cities as Samuel (2009) lists include Lagos, Ibadan, Osogbo, Abeokuta, Akure, Ado-Ekiti, Oyo, Ijebu Ode, Ogbomoso, Ondo, Ilesa, Iseyin and Ile-Ife. The well-vegetated area encourages farming, and other occupations include weaving, dyeing, smithing, leather work, and pottery.

From time immemorial, Yoruba verbal art has frequently referenced the natural world. Animals and other natural elements feature prominently in their songs and poems, which are viewed as a single interchangeable art form. According to Euba (1977) most Yoruba folklore is accompanied by songs. Yoruba music is also philosophical, and sometime imports some non-human elements to drive home a lesson. Omojola (2005, 165), in his study of the works of Bankole and Euba, alludes to the fact that musical traditions in Africa provide the most important expressive medium for the rich folklore that abounds on the continent. In the same vein, the Yoruba have a remarkable love for comparative descriptions of nature around them in form of opposites. Agbe, aluko, and lekeleke are birds of special beauty and natural significance to Yoruba people and poets. A common Yoruba saying is “agbe lo l’aro, aluko lo l’osun, lekeleke lo l’efun” (the woodcock owns the blue dye, another species of woodcock owns the camwood, and the cattle egret owns the white chalk). This describes the beauty of the feathers that grace the birds roaming the Yoruba skyline.

Animals such as the tortoise, goat, buffalo, elephant, dog, lion, snake, snail, fish, and monkey are represented in Yoruba songs and poems, as are birds like the woodcock, parrot, white feather bird, and hen. There are also references to products from plants like palm oil, bitter kola, camwood, and chalk, and trees like the iroko, araba, and big tree. Natural features like the river and stars are also represented. Olaosun (2016, 48) discusses musical “ecosemiosis” in popular Fuji singer Ayinde Sikiru Barister’s song about three birds and Apala singer Haruna Ishola’s song about the natural elements. He explains how these songs signify the hierarchical level among Fuji and Apala musicians. The current paper differs, though, in analyzing the discourse on birds, animals and other natural elements among the Yoruba people as it relates to their environmental degradation and need for sustainability. It also examines the environmental disasters and struggles that confront the Yoruba people and, by extension, Nigeria and the rest of the globe on a daily basis. One such disaster is the flood of Ibadan, one of the major Yoruba cities.

Themes in Christopher Omotoso’s “Eye Orofo” Song

Christopher Omotoso was born in the 1960s in the Nigerian state of Ibadan Oyo. He started his musical career as a church choir boy, received degrees in music education in the 1990s, and completed an M.A. in musical performance in 2012. He has worked as a teacher at multiple levels, and currently teaches in the Federal College of Education in Okene. He has composed several musical pieces and released several albums, and is married with children.

Numerous themes are found in “Eye Orofo,” including moral values, moderation and environmental sustainability consciousness. Before going into details about these themes, I will describe the African Grey Parrot.

The African grey parrot, Psittacus erithacus, is a medium-sized, dusty-looking gray bird, almost pigeon-like, but with a bright red tail, intelligent orange eyes, and a stunning scalloped pattern to its plumage. Its understated beauty and brainy no-nonsense attitude keep this parrot at the peak of popularity. This parrot is one of the oldest psitticine species kept by humans, with records of the bird dating back to biblical times (Lafeber 2018). In Nigeria the bird has been hunted and kept as a pet in the house. The African grey parrot is one of the most talented talking/mimicking birds on the planet, giving it quite a reputation among bird enthusiasts. Not only do bird-keepers love this intelligent bird, it is one of the most recognizable species to bird novices as well. Much of the grey’s appeal comes from this ability. It is able to repeat words and phrases after hearing them just once or twice. This bird reaches full talking ability around a year of age, and most individuals become capable mimics much earlier. According to the Lafeber company, “the African grey parrot is not just a top talker—this bird is also known for its extreme intelligence.” African grey parrots generally inhabit savannahs, coastal mangroves, woodlands and edges of forest clearings in their West and Central African range. Though the larger of the African grey subspecies is referred to as the Congo African grey, this bird actually has a much wider natural range in Africa, including Nigeria, the southeastern Ivory Coast, Kenya, and Tanzania.

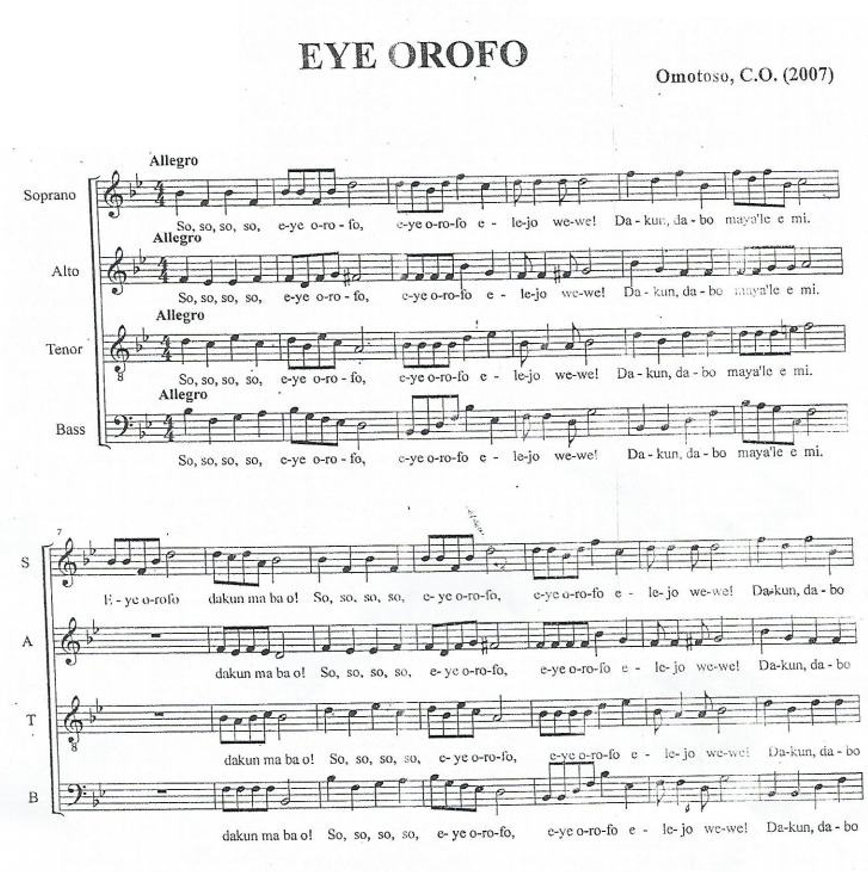

Christopher Omotoso starts his song by imitating the bird call “so so so so,” shown in the first bar of the musical score (ex. 1). In making this sound, he points to human folly, in line with the Yoruba understanding that compares a chattering bird to a talkative gossip. In imitating the birdsong, he captures its meaning and the emotion it provokes in people. The following excerpt from the song text explains this:

So so so so eye orofo

Eye orofo elejo wewe

dakun dabo mayale mi

Eye orofo, dakun ma ba o

Agbo teku wi feye,

Agbo teye wi feku

Oro gbogbo ni soju ara ile wa

Eye orofo, dakun ma ba o

“So so so so” the parrot says/sounds

The parrot is talkative

Parrot, do not come to my house

Parrot, do not fly to my house

It tells rats about birds

And inform birds about rats

It gossips about everything around

Parrot, do not fly to my house

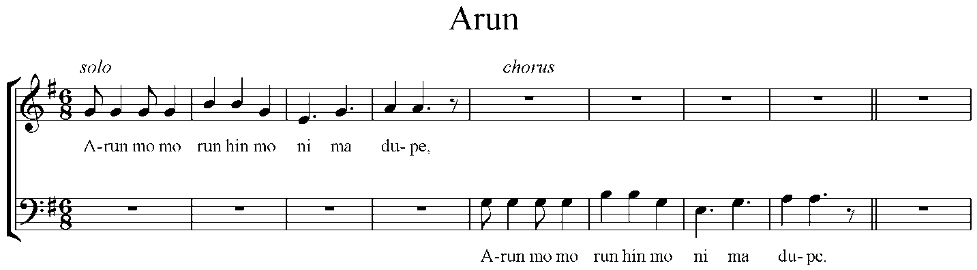

A song by Maku Sunday, a Nigerian folk singer, includes similar lines on the theme of talkativeness, and other issues related to the use and misuse of mouth:

Arunmomo run hinmoni ma dupe

Arunmomo run hinmoni ma dupe

May my mouth not destroy my virtues,

May my mouth not destroy my character

Alimat Ajao, another popular Nigerian female singer, also sings about the self-destructive mouth of the parrot:

Enuorofoniyio pa orofo

Kenu mi kiomapami o

Enuorofoniyio pa orofo

Kenu mi kiomapami o

It is the parrot’s mouth that will destroy it,

May my mouth not lead to my destruction,

It is the parrot’s mouth that will destroy it,

May my mouth not lead to my destruction

In referring to the mouth, both song texts refer not simply to speech but also to what goes into the mouth—food and drinks. “Mouth” in Yoruba also implies money, corruption, and taking what does not belong to one legitimately. This can include any kind of greed and graft, such as stealing from the government, corruption, and money laundering, all of which pervade Nigeria. The song addresses the corruption of stealing money and hiding it in a burial ground—a situation that was reported recently in Nigeria. The birdcall here represents a lack of morality and moderation in the Yoruba socio-cultural world view.

Furthermore, “elejo wewe” (talkative) culturally connotes loose talk, loose virtue and someone with low integrity. Yoruba culture revered truthfulness. As Awoniyi (1975, 377) asserts, the truth is meant to be practiced both publicly and privately. In his analysis of Yoruba omoluabi (virtue), he further notes that appropriate songs and proverbs are literally sung into the ears of the child, motivating their subconscious mind with values and problems of truthfulness. Awoniyi (1975, 377) further notes that a Yoruba child is told “iro pipa ki iwi pe ka ma loowo lowo, ile di da ki iwi peka ma dagba, sugbon ojo ati sun lebo” (lying does not mean that one will never be rich, treachery does not mean one will never live to old age, but it is the day of death [judgment] that should be one’s primary concern).

Through negative example, Omotoso’s “Eye Orofo” song reveals the truthfulness needed for good interpersonal relationships. In the line “agbo teku wi feye agbo teye wi feku,” the parrot reveals the rat’s secrets to the bird and vice versa. This is symbolic of human relations, and the need for friendliness and neighborliness. Here the rat and bird typify different personalities with whom we have to peacefully coexist. Abimbola, in enumerating iwapele, the concept of good character, argues that “a man’s Iwa (character) is what can be used to characterize his life especially in ethical terms” (1975, 389). “Eye Orofo” signifies humans who live like the talking bird. Abimbola further advises that, contrary to the nature of the orofo bird, “every individual must strive to have a good character in order to be able to lead a good life in the social structure.” Christopher Omotoso’s “Eye Orofo” also aims to teach this message.

Abimbola notes that “the Yoruba regard good character as the most important of all moral values” (1975, 395). Ogunyemi (2018) explains that “Yoruba people’s philosophy hangs on good character, and interpersonal relationships”; he notes that “good character will ultimately lead to good interpersonal relationships.” Likewise, in a personal communication from 2018 Adebowale notes “that the reason why government officials steal the public funds is because of loss or lack of good character and virtues.” Most Nigerian leaders lack the virtues to be leaders because most of them embezzle public funds meant to repair and maintain good roads, provide basic equipment for the hospitals and good education for the young ones. The song exemplifies good character and also cautions corrupt politicians and citizens about the need to embrace virtuous lives.

The song therefore connects money, corruption, and morality. As stated, it is the lack of virtues that breeds corruption and morality. As the song text vividly says, “maya le mi” (don’t come near my house). The song encourages virtuous people to segregate themselves from corrupt people by not going close to them or partaking in their corruptions.

Other sections of the song relate to the children’s “moonlight song,” which describes the different aesthetic features of some birds. One lesson that is paramount in this text is that beauty does not translate to character. The Yoruba saying “iwalewa” (good character is the real beauty) aptly expresses that one must possess omoluabi (virtue) in all dealings with the community.

These folktales can be examined in conjunction with Olayemi’s assertion that:

the setting of the Yoruba folktale is not only the world with which the Yoruba are familiar… in the Yoruba folktale there is evidence of practically every aspect of the supernatural in which the people believe. This is not surprising for stories reflect what people do, what they think, how they live and have lived, their values, their joys and their sorrows (1975, 959–960).

The ecomusicological explications of the folktale are built on the talking bird and the wisdom of keeping silence when needed. Mayowa, who observed the song being performed at the Federal College of Education in Okene Kogi state, feels that the messages derived from “Eye Orofo” include “truthfulness, good character, and unity among friends and colleagues, among several lessons” (Emmanuel 2016). He further notes that “some individuals find it difficult to keep secrets, and some are perpetual liars in society, which the song represents.”

Mary, another observer notes that “the song, though in western musical style, is rooted in Yoruba cultural ideals and socialization. It teaches one to mind one’s own business and issues” (Omotoso 2016). Finally, Henry asserts that Christopher Omotoso’s song is a timeless message for the old and young among the Yoruba (James 2016).

Christopher Omotoso’s song texts also exemplify the need to respect the environment and the non-human spirits that inhabit it. Modernity considers deities residing in nature as nonexistent—certainly not beings worthy of respect and worship. This recent act of erasing the deities has brought environmental crises to the world. Africa has many deities residing in natural elements such as mountains, trees, oceans, rivers and valleys, among others. They preserve the natural phenomena where they abide, making those elements friendly to humans. Also, the traditional belief in human-nonhuman relationships, which demanded regular worship of such deities, existed until modernity caused them to cease.

Christopher Omotoso’s song speaks to a close relationship between interpretations of environmental disasters and an indigenous belief system in which deities are a central feature. The following song excerpt explains this:

Fenu menu fete mete

Adifafunwef’Alaba

Toriakujulori obi,

Okiakujuonipele,

Akujudahun wipe enu re niopa o

Keep your mouth and lips closed,

An oracle was consulted for Alaba’s servant,

He saw a spirit on a kola nut tree,

He greets the spirit,

The spirit replies that your mouth will kill you

The song text here tells a story about the servant of a chief named Alaba. The servant went to the farm and saw a spirit on the kola nut tree, who revealed that the servant found it difficult and morally tough to control his mouth.

Yoruba people believe in supreme beings that inhabit nature. Due respect and honor should be paid to these beings, which Alaba’s servant could not do. According to oral lore, when the servant arrived at the community he started telling everybody that he had seen the ghost, greeted it, and been greeted back. This challenged the Yoruba belief that ghosts cannot be seen because they are superhuman. Alaba’s servant was directed to go and show the community where the ghost was, warned that if they did not see the ghost he would be killed. Everybody went to the tree and could not see the ghost, leading to the servant’s death. The lesson in the folktale presented in song here is that respect for supreme beings and their abode is a crucial part of the moderation, virtues and lifestyles of community members in Yoruba land.

The song text is also concerned with ecological degradation in Nigeria. Two cases are considered here.

Christopher Omotoso’s birdsong engages the environmental degradation experienced in the southern part of Nigeria through the neglect of the non-humans that inhabit them, as his song text explains. The two most prominent incidents are the Ibadan flood disaster and Niger Delta oil exploitation and land degradation.

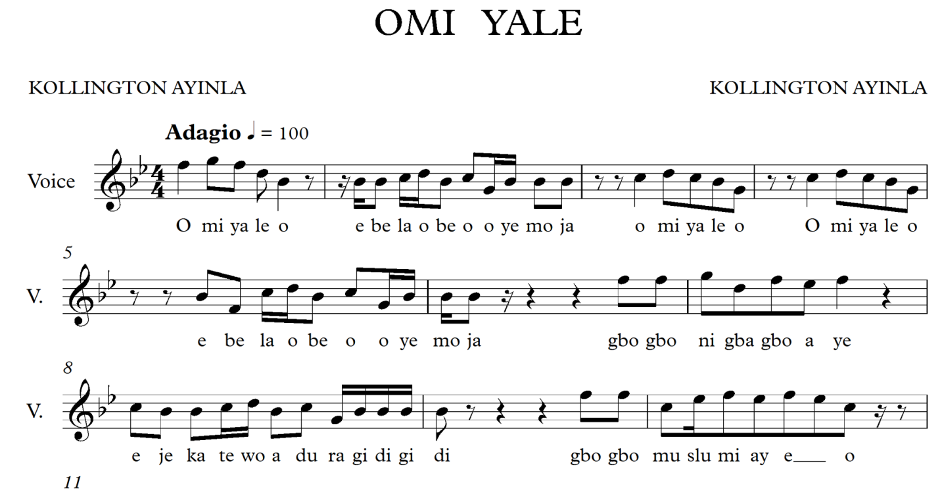

A song by Kollington Ayinla, a popular Yoruba Nigerian musician, supports Christopher Omotoso on the need to respect the deities that inhabit nature.

Omi yale o—

ebe lanbe o Yemoja

Omi yale o, Omiyale o

Ebe lanbe o Yemoja

The flood has destroyed the houses

We are pleading with you Yemoja

Flood disaster, flood disaster

We are pleading with you Yemoja

Yemoja is the spirit that inhabits rivers and waters. According to local belief systems, the lack of regular sacrifices to this spirit is held to be the reason for the flood. Not only do the modern religions of Christianity and Islam forbade the worship of Yemoia, but people trespasses Yemoja’s home and abode by carrying refuse there. This resulted in the recurrent flood in Ibadan.

Ibadan is located in southwestern Nigeria. It is the capital of Oyo State, and was historically reputed to be the largest indigenous city in Africa south of the Sahara. Ibadan was the administrative center of southwestern Nigeria, a status it held from the days of British colonial rule until other states like Ondo, Ogun and later Osun were created. It is situated 78 miles inland from Lagos, and is a prominent transit point between the coastal region and the areas to the north of the country. In 2006, Ibadan’s population was estimated at around 3,800,000 (Oladapo 2011). According to my interlocutors, however, the population by 2014 was closer to 9,000,000.

When the rain stops in Ibadan, it often reveals heaps of waste (carried down by erosion) at the bottom of the hills and mountains that constitute the living areas in the city. This exposes the city and its inhabitants to the risk of flooding. The hilly terrain also makes it difficult to easily access water due to the low-level underground water table (Olayinka 2010, 12). The city’s built-up areas have two main streams, the Ogunpa and Kudeti. Both streams and their tributaries serve commercial purposes, and are surrounded by open market stalls and popular markets. The consequence of this is a sizeable production of market waste. The streams become avenues into which this unregulated waste is poured, with a lack of regular government attention or proper legislative intervention (Ajala 2011).

These realities have on many occasions exposed Ibadan city to heavy flooding, accounting for heavy destruction of lives and properties. Apart from incidents in the 1950s–1970s, a devastating flood known as omiyale (literally meaning “water has flooded the house”), occurred in 1982, when Ogunpa stream, connected to the Ona stream, flooded its banks and swept off many nearby inhabitants and their properties. Many of the victims had defied local regulations against building along the river. Since then, a flood disaster has become an annual event across Ibadan, suggesting that the 1982 experience was not enough of a lesson. In 2011, an even more devastating flood occurred in Ibadan, surpassing the earlier ones.

Another environmental degradation in Nigeria has occurred in the Niger Delta region. The Delta is made up, by some estimates, of over sixty ethno-linguistic groups, with the Ijaw representing the largest. Africa’s most extensive wetlands are located in the Niger Delta, the center of Nigeria’s oil production, with approximately 2.5 million barrels of oil produced every day (Timsar, 2015; Bassey 2012; Okuyade 2011; Okunoye 2008). After more than fifty years of oil production in the Delta, the resulting land, air, and water pollution (gas flares, spills, and leaks from old infrastructure) is choking this vast ecosystem. The health costs, loss of livelihood, and stagnant chances of employment are devastating for the youth.

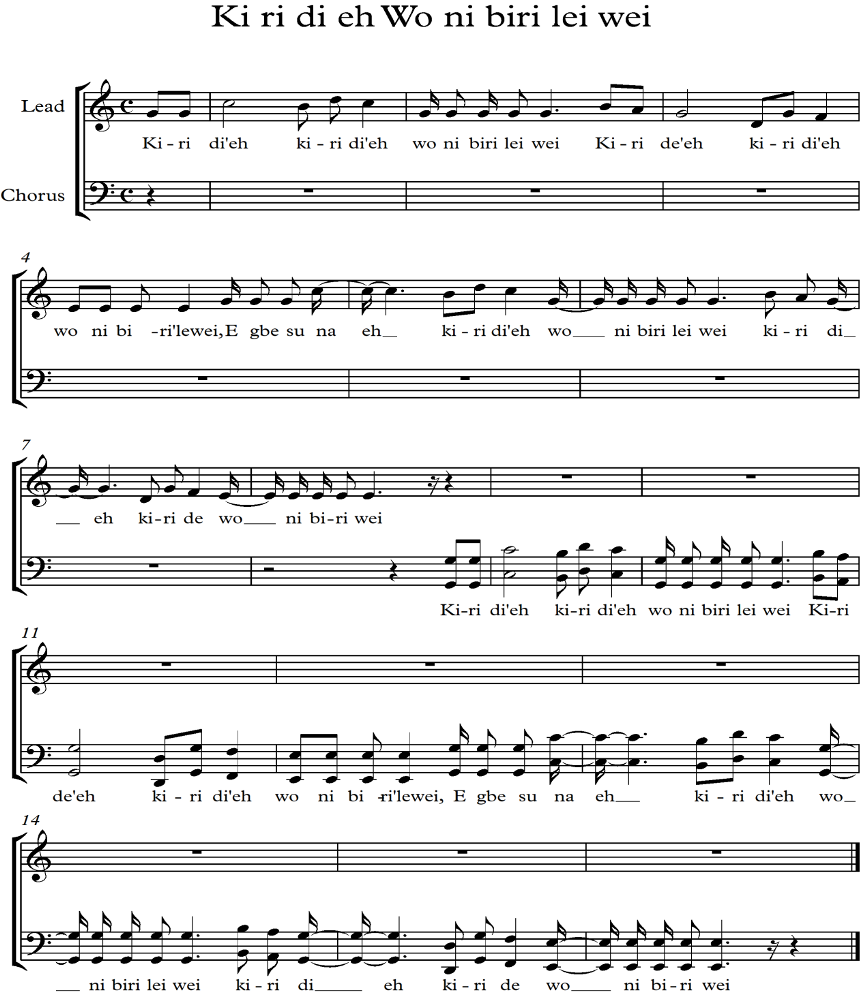

Songs by worshipers of the deity Egbesu in the Niger Delta support Christopher Omotoso on the need to respect the non-humans that reside in nature. One of these songs says that lack of due respect to the deity might have been part of the devastating environmental crisis experienced in the Delta.

Kiri di eh, kiri di eh, wonibiri lei wei

Egbesuna eh, kiri di eh, wo nibiri lei wei

Kiri di eh, kiri di eh, wo nibiri lei wei

Egbesuna eh, kiri di eh, wo nibiri lei wei

We welcome you with all honor

Egbesu, the guardian of our life and land

We welcome you with all honor

Egbesu, the guardian of our life and land

These two ecological problems in Nigeria result from human lack of respect for the non-humans that inhabit the water and the land as well as the environment—something that Christopher Omotoso’s birdsong helps to reinvigorate. The songs help create advocacy for environmental sustainability relating to both the Ibadan flood and Niger Delta oil extraction, tragedies that have arisen due to the human lack of moderation and respect for the environment.

Conclusion

This paper has discussed the ecomusicological significance of “Eye Orofo.” It examined the socio-cultural and ecological signification of the song involving birds, trees, and other natural elements as they are imbued in Yoruba cultural belief and traditions of morality, caution, moderation, respect for the environment, and sustainability. The text of the song showcases the character of a bird and its anti-social, anti-communal communication approach. In contrast, the song text promotes the Yoruba belief of virtues and good character, encouraging listeners to be careful and respect nature. Also, the need to respect deities that reside in nature is imperative for survival. The song shows that the lack of respect for deities leads to death of people, and, by extension, the environment. Our world needs peace and security. At the same time, humans must recognize their limitations as they engage in environmental activities. In conclusion, there are still many Yoruba songs on ecological and cultural themes, beckoning for studies which other researchers will need to embark on in the future.

Bibliography

Abimbola, Wande. 1975. “Iwapele: The Concept of Good Character in Ifa Literary Corpus.” In Yoruba Oral Tradition, edited by Wande Abimbola, 389–420. Ibadan, Nigeria: University of Ibadan Press.

Adebowale. 2018. Personal Communication Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Agawu, Kofi. 1984. “The Impact of Language on Musical Composition in Ghana: An Introduction to the Style of Ephraim Amu.” Ethnomusicology 28, no. 1 (January): 37–73.

Agawu, Kofi. 2009. Music as Discourse: Semiotic Adventures in Romantic Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ajala, Aderemi. 2011. “Space, Identity and Health Risks: A Study of Domestic Wastes in Ibadan, Nigeria.” Health, Culture and Society 1, no. 1: 1–21.

Allen, Aaron S. 2011. “Ecomusicology: Ecocriticism and Musicology.” Journal of the American Musicology Society 64, no. 2: 391–393.

Allen, Aaron S., Jeff Todd Titon, and Denise Von Glahn. 2014. “Sustainability and Sound: Ecomusicology Inside and Outside the Academy.” Sound and Politics 8, no. 2: 1–20. DOI: 10.3998/mp.9460447.0008.205.

Awoniyi, Timothy. 1975. “Omoluabi: The Foundational Basis of Yoruba Education.” In Yoruba Oral Tradition, edited by Wande Abimbola, 357–388. Ibadan, Nigeria: University of Ibadan Press.

Baptista, Luis F., and Robin A. Keister. 2005. “Why Birdsong is Sometimes Like Music.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 48, no. 3, 426–443.

Bassey, Nnimmo. 2012. To Cook A Continent: Destructive Extraction and the Climate Crisis in Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Pambazuka Press.

Doolittle, Emily L. 2007. “Other Species’ Counterpoint: An Investigation of the Relationship Between Human Music and Animal Songs.” PhD dissertation, Princeton University.

Emmanuel, Mayowa. 2016. Personal communication, 11 July, Lagos, Nigeria.

Euba, Akin. 1977. “An Introduction to Music in Nigeria.” Nigerian Music Review 1: 1–38.

Euba, Akin. 1987. “The African Guitar 3, Knowledge of Traditional Music is Key to Performance.” African Guardian, 4 June.

Euba, Akin. 1989. Essays on Music in Africa 2: Intercultural Perspectives. Elekoto and Bayreuth: Iwalewa-Haus.

Euba, Akin. 1999. “Towards an African Pianism.” Intercultural Musicology: The Bulletin of the Center for Intercultural Music Arts 1, no. 1-2): 9–12.

Egya, Sule Emmanuel. 2015. “Nature and Environmentalism of the Poor: Ecopoetry from the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 28, no. 1: 1–12. DOI: 10.1080/13696815.2015.1083848.

Feld, Steven. 1991. “Voices of the Rainforest.” Public Culture 4, no. 1: 131–140.

Glotfelty, Cheryll. 1996. “Introduction: Literary Studies in an Age of Environmental Crisis.” In The Ecocritical Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology, edited by Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm, xv–xxxvii. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Guy, Nancy. 2009. “Flowing Down Taiwan’s Tamsue River: Towards an Ecomusicology of the Environmental Imagination.” Ethnomusicology 53, no. 2: 218–248.

Impey, Angela. 2008. “Sound Memory and Dis/placement: Exploring Sound, Song and Performance as Oral History in the Southern African Borderlands.” Oral History Journal 36, no. 1: 33–44.

Impey, Angela. 2013a. “Keeping in Touch Via Cassette: Tracing Dinka Songs from Cattle Camp to Transnational Audio-letter.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 25, no. 2: 197–210, DOI: 10.1080/13696815.2013.775038.

Impey, Angela. 2013b. “Songs of Mobility and Belonging: Gender, Spatiality and the Local in Southern Africa’s Transfrontier Conservation Development.” Intervention: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies 15, no. 2: 255–271. DOI: 10.1080/1369801X.2013.798475.

James, Henry. 2016. Personal commuication, 23 June, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Lafeber Company. 2018 (last modified). “African Grey Parrot.” https://lafeber.com/pet-birds/species/african-grey-parrot/.

Lambert, W. G. 1970. “The Sultantepe Tablets: IX. The Bird Call Text.” Anatolian Studies 20: 111–117.

Lwanga, Charles. 2013. Bridging Ethnomusicology and Composition in the First Movement of Justinian Tamusuza’s String Quartet Mu Kkubo Ery’Omusaalaba. Analytical Approaches to World Music 3, no. 1. http://www.aawmjournal.com/articles/2014a/Lwanga_AAWM_Vol_3_1.html.

Mensah, Atta Annan. 1997. “Compositional Practices in African Music.” In The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music vol. 1: Africa, edited by Ruth M. Stone. New York: Routledge.

Nzewi, Meki. 1999a. “Modern Art Music in Nigeria: Whose Modernism?” Unpublished seminar paper presented at the Department of Music, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa.

Nzewi, Meki. 1999b. “Challenges for African Music and Musicians in the Modern World Music Context.” In Intercultural music, vol. 2, edited by Cynthia Tse Kimberlin and Akin Euba, 201–225. Richmond: MRI Press.

Ogunyemi, Sesan. 2018. Personal communication, 12 July, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Okunoye, Oyeniyi. 2008. “Alterity, Marginality and the National Question in the Poetry of the Niger Delta’. Cahiers d’etudes africaines 191: 413–436. DOI: 10.4000/etudesafricaines.11742.

Okuyade, Ogaga. 2011. “Rethinking Militancy and Environmental Justice: The Politics of Oil and Violence in Nigerian Popular Music.” Africa Today 58, no. 1: 79–101.

Oladapo, Akin. 2011. “Environmental and Flood Degradation in Ibadan City, Nigeria.” Master’s dissertation, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

Olaosun, Ibrahim. 2016. Nature Semiosis in Two Nigerian Popular Music. Ife-Ife, Nigeria: Obafemi Awolowo University Press.

Olayemi, Victor. 1975. “The Supernatural in the Yoruba Folktale.” In Yoruba Oral Tradition, edited by Wande Abimbola, 957–972. Ibadan: University of Ibadan Press.

Olayinka, Abel Idowu. 2010. “Imaging the Earth’s Subsurface.” Lecture presented at the University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, 11 February.

Omojola, Bode. 2005. “Folklore, Cultural Meaning and Text-Setting in Modern Yoruba Vocal Music.” In Multiple Interpretations of Dynamics of Creativity and Knowledge in African Music Traditions, edited by Bode Omojola and George Dor, 165–186. Point Richmond, CA: MRI Press.

Omojola, Bode. 2006. Popular Music in Western Nigeria: Theme, Style and Patronage System. Ibadan: Institut Francais de Recherche en Afrique.

Omotoso, Mary Tolufashe. 2016. Personal communication, 23 June, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Onyeji, Christian. 2002. The Study of Abigbo Choral-Dance Music and its Application in the Composition of Abigbo for Modern Symphony Orchestra. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Onyeji, Christian. 2005. “Research-Composition: A Proposition for the Teaching of Composition from the Traditional Perspective.” In Emerging Solutions for Musical Arts Education in Africa, edited by Anri Herbst, 250–266. Cape Town, South Africa: African Minds.

Ozah, Marie Agatha. 2013. “Building Bridges between African Traditional and Western Art Music: A Study of Joshua Uzoigwe’s Egwu Amala.” Analytical Approaches to World Music 3, no. 1. http://www.aawmjournal.com/articles/2014a/Ozah_AAWM_Vol_3_1.html

Pedelty, Mark. 2008. “Woody Guthrie and the Columbia River: Propaganda, Arts and Irony.” Popular Music and Society 31, no. 3: 325–337.

Pedelty, Mark. 2013. “Ecomusicology, Music Studies, and IASPM: Beyond ‘Epistemic Inertia.’” IASPM Journal 3, no.2: 33–47.

Pont, Graham. 2004. “Philosophy and Science of Music in Ancient Greece: The Predecessors of Pythagoras and their Contributions.” Nexus Network Journal 6, no. 1: 17–29.

Ramnarine, Tina K. 2009. “Acoustemology, Indigeneity, and Joik in Valkeapaa’s Symphonic Activism: Views from Europe’s Arctic Fringes for Environmental Ethnomusicology.” Ethnomusicology 53, no. 2: 187–217.

Rees, Helen. 2016. “Environmental Crisis, Culture Loss, and a New Musical Aesthetics: China’s ‘Original Ecology Folksongs’ in Theory and Practice.” Ethnomusicology 60, no. 1: 53–88.

Rehding, Alexander. 2011. “Ecomusicology: Between Apocalypse and Nostalgia.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 64, no. 2: 409-414.

Rothenberg, David. 2005. Why Birds Sing: A Journey into the Mystery of Bird Song. New York: Basic Books.

Samuel, Kayode M. 2009. “Female Involvement in Dundun Drumming Among the Yoruba of Southwestern Nigeria.” Master’s thesis, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

Silver, Michael B. 2015. “Birdsong and a Song about a Bird: Popular Music and the Mediation of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Northeastern Brazil.” Ethnomusicology 59, no. 3: 380–397.

Sowande E. J. 2003. A Dictionary of the Yoruba Language. Ibadan, Nigeria: University Press.

Taylor, Hollis. 2011. “Composers’ Appropriation of Pied Butcheredbird Song: Henry Tate’s ‘Undersong of Australia’ Comes of Age.” Journal of Music Research online 2: 1–28.

Taylor, Hollis, and Andrew Hurley. 2015. “Music and Environment: Registering Contemporary Convergences.” Journal of Music Research Online 6: 1–18.

Timsar, Rebecca Golden. 2015. “Oil, Masculinity, and Violence: Egbesu Worship in the Niger Delta of Nigeria.” In Subterranean Estates: Life Worlds of Oil and Gas, edited by Appel Hannah, Mason Arthur, and Watts Michael, 72–90. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Titon, Jeff Todd. 2013. “The Nature of Ecomusicology.” Música e Cultura: revista da ABET 8, no. 1: 8–18.

Urquhart, Thomas. 2004. For the Beauty of the Earth: Birding, Opera, and Other Journeys. Washington, DC: Shoemaker & Hoard.

Uzoigwe, Joshua. 2001. “Tonality Versus Atonality: The Case for an African Identity.” In African Art Music in Nigeria, edited by M.A. Omibiyi-Obidike, 161–174. Ibadan: Stirling-Horden.

Vidal, Tunji. 2016. “Nigerian Music Industry: The Falling Standard.” Paper Presented at the 70th Birthday Anniversary Celebration of the Legend of Nigerian Music Industry, King Sunny Ade, MFR. 28 September.