by Denise Von Glahn and Mark Sciuchetti

Authors’ Note

The following article is the result of a collaborative project between Denise Von Glahn, Professor of Musicology at Florida State University (FSU), and Mark Sciuchetti, newly appointed Assistant Professor of Geography at Jacksonville State University. They met at FSU while Sciuchetti was pursuing degrees in musicology and cultural geography. The article started with both authors independently studying Annea Lockwood’s 1982 piece A Sound Map of the Hudson River. Intrigued by how the river might sound today, Sciuchetti proposed his own mapping project of the river, but rather than recording along its shore, as Lockwood had done, he and a crew journeyed on the water. Von Glahn’s remarks frame the beginning and end of the article; Sciuchetti’s journal entries and recollections provide an essential and complementary first-hand account of his experiences. Their two voices come together in the middle section.

Mapping Sounds and Places

A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.

The picture may distort: but there is always a presumption that something exists,

or did exist, which is like what’s in the picture.Susan Sontag (1973, 5)

Sontag’s observations about photographs might well be applied to maps, those diagrammatic representations of places whose details suggest that something exists. The realization that multiple maps can chart the same place dramatically differently, however, tests any claims of “incontrovertible proof” that often accompany the deployment of details in service of explanations. As with photographs, we are justified to question the completeness of any map, what it might prove or distort, perhaps even its veracity. Although it is comforting to think that topographical features identified on a map are terra firma and resistant to modification, they are not. Land forms change on their own: fault lines expand, dust storms redistribute inches of top soil, coastlines recede, volcanoes erupt, and islands emerge. In addition, humans level mountains and clear-cut forests, they divert rivers, and create lakes. A photographer or cartographer wields similar human agency. She makes decisions regarding what to include, exclude, emphasize, or understate depending upon larger goals for the project, her perspective in relation to the subject, the technology and materials used to create the schema, and cultural values that consciously and subconsciously inform her understanding of the object’s import. Considering these multiple contingencies, it is wise to question what we see when we look at a photograph or a map.[1]

For true cartophiles, there are never enough maps; each rendering provides unique information about that which it portrays. And the same is true of environmental listeners and their sound maps. Recordists decide what to capture depending upon the larger goals of the project, which equipment they’ll use, where to point or drop their microphones, and how to treat their materials. Weather conditions present another variable. Although the immediate place doesn’t change when shrouded in fog or scorched by sun, its aural fingerprint does thanks to the sounds associated with various forms of precipitation and winds and their amplifying and deadening properties. We hear places differently when they are in motion or still. When recordists process their materials, they make additional choices: whether and how much to filter or edit the raw materials, how to remove unwanted “noise,” or how to adjust levels to balance and achieve the effects desired. For all their incontrovertible proof, sound maps, like traditional maps and photographs, are constructions; they are creative products of their makers’ imaginations, which had been excited by something that, we presume, existed.

Although there are few systematically created professional sound maps of specific locations (as compared to spontaneous, one-off, amateur recordings on personal hand-held devices), and the number of individual places that have been professionally recorded multiple times over a period of years is still small, there is a growing catalogue; those that exist bear witness to the mutability of sounds, places, and our perceptions of them.[2] As soon as a vibration stirs the air it changes. The transience of sound is among its fundamental qualities. Capturing a material that is at its essence dynamic, however, raises questions regarding what is being preserved or presented in any sound map. Which moment in a sound’s existence has the recordist captured? Which moment does a listener hear? It is not surprising that when multiple sound maps of a single location are compared, differences are likely to outnumber similarities. We don’t need decades of separation or human-exacerbated climate change for this to be the case. Sound maps serve different purposes, are filtered through different cultural understandings, and are the products of different technologies employed with different levels of expertise.

Comparing composer Annea Lockwood’s 1982 piece A Sound Map of the Hudson River with cultural geographer Mark Sciuchetti’s 2017 recordings of similar places along the waterway is a bit like the proverbial comparison of apples and oranges. Lockwood’s work was a response to a commission; Sciuchetti’s was a personal exploration of affectual experiences. Nonetheless the exercise reveals the complexities inherent in decoding any sound map. We come to understand how context, perspective, equipment, technological know-how, and cultural values matter. What we hear depends upon who and where we are and when, and what we are listening to and why, and not necessarily the place itself. As Annea Lockwood understood: the recordist-listener is the composer; the recordist-listener decides what is there and what isn’t. In creating sound maps, it’s all about who’s listening, recording, and then listening again.

Mapping the Hudson

Like Niagara Falls, images of the Hudson River and its picturesque valley in upstate New York supplied the subject matter of postcards and lithographic prints and were disseminated widely throughout the nineteenth century. Mansions and hotels sprang up along its banks providing homes for the wealthiest and a brief opportunity to enjoy its restorative properties for thousands of vacationing others. But no one was more responsible for the romanticization of the River and its valley than a group of New York City-based artists whose similar aesthetic earned them the name the “Hudson River School.” Their wholly idealized landscapes of the place fed the nineteenth-century need for evidence of America’s Edenic promise. They set off their light-filled renderings within ornate gilt frames that pulsed their own warm glow upon the already luminescent canvases. To some extent Lockwood’s sound map functions as an aural analogue to one of these works. She renders the different times of day and season—including background, middle ground, and foreground sounds—in the most positive light.[3] Even the six-minute segment given to the sound of a train along the river bank—Track 10 “Stuyvesant (tugboat and train)”—becomes a paean to this now-romanticized nineteenth-century mode of transportation. The train was most often associated with settling the nation: it got goods to people, people across the continent, and symbolized American promise and achievement.[4] Lockwood’s train, echoing across the River valley, recalls that idealized past. Mark Sciuchetti freely admits that his river mapping project may have started, in part, as a search for an idealized past, but what he encountered on the rough waters of Long Island Sound immediately changed the project. His first-person account later in this article tracks that metamorphosis.

I have listened to both recordists’ renderings, and I have also listened to the Hudson River. To be fair, I was a child when my family regularly vacationed in the Hudson Valley, so my recollection of the river’s sounds is part of a much larger sensory memory. A half-century of distance has also likely distorted my original perceptions. But I share the place with Lockwood and Sciuchetti and find myself at home somewhere in the middle of their sound maps, both literally and metaphorically; our paths cross between Hudson, Newburgh, and Yonkers, New York, and along a spectrum of romantic and everyday (mundane) readings of the Valley. An overview of Lockwood’s seventy-plus minute “aural journey,” A Sound Map of the Hudson River, provides a point of departure for this brief comparative study. Her piece was written on a commission from the Hudson River Museum, which is situated along the eastern bank of the Hudson in Yonkers, New York, a large bedroom-community a few miles north of Manhattan. The Hudson River valley creates a dramatic setting for the city and the museum. The shape and overall aesthetic of Lockwood’s piece were influenced by the Museum’s location, its regional historicizing mission, and its aesthetic vision: the last named owes a large debt to the Museums’ significant collection of Hudson River School paintings and their influence on the many associations we have attached to the river for close to two hundred years (listen to an excerpt of Lockwood’s A Sound Map of the Hudson River).

From the beginning, with funding underwritten in part by the New York State Council on the Arts, Lockwood’s sound map was imagined as an installation that celebrated the waterway, the region, and the state.[5] It was not composed to stand alone as a traditional piece of concert music, or be listened to separate from the panoramic Hudson River setting that was visible through a wall of windows in the listening space, although it rewards doing just that. It could be argued that listening away from the museum space invites additional imagined journeys. It was part of a larger multi-media conception. Lockwood explained the piece in her exhibit notes:

Each stretch of the river has its own sonic textures, formed by the terrain, varying according to the weather, the season, and downstream, where human sounds are intimately part of the river’s sound from hour to hour.

Her references to the terrain connect the sounds to the geological history of the river basin: from its origins in the last North American glacial period, the Late Wisconsinan Glaciation (25,000 to 21,000 years ago), through to the present. Lockwood orients visitors to what they are about to hear based upon where they are in the museum space.[6] The piece becomes a soundtrack to the visual installation and a unique aural history:

From the map on the wall and from the clock you will be able to identify which stretch of river you are listening to and gain a sense of the local topography and the date and time of day when the recording was made. This is a two-hour tape which begins on the even hours.

One site, Twombly Landing, can be seen from this window, below the Palisades and directly opposite the Museum.[7]

In organizing the recordings, the composer began with “the source of the river, Lake Tear of the Clouds in the high peak area of the Adirondacks,” and worked her way along the shore “downstream to the Lower Bay and the Atlantic” (Lockwood 1989). Altogether there are fifteen recorded sites along the 315-mile waterway: the first five within proximity of each other at the river’s source in the Mt. Marcy area in northern upstate New York; the next four are further south moving from the Hudson Gorge through Luzerne, and Glens Falls; and the last six include recordings made at Stuyvesant New York, a town just twenty miles south of the state capital in Albany, at Staatsburg, Garrison, Iona Island in Stony Point, Englewood Brook Falls at the Palisades Interstate Park, and finally at Great Kills Beach, which is operated by the National Park Service in Staten Island, and is the southernmost part of the state. At this point the Hudson joins with the Atlantic Ocean. Given the gradual journey from the most remote to the most populated areas along the river, it is no surprise that Lockwood’s fifteen recordings register increasingly human-made sounds—distant trains, the squeaks of oarlocks on moored boats, and motors before returning to the water sounds of the sea alone. On balance the composition favors, overwhelmingly, sounds of the non-human natural world: water in its infinite variety, birds, ducks, seagulls. At no point do listeners hear the composer as she walks along the water’s edge or navigates the terrain or adjusts her equipment, and this was intentional on Lockwood’s part. The recordings appear to be the product of an omniscient, but inaudible recordist: perhaps an “every-ear.” Lockwood assured visitors that her recordings had “not been processed nor juxtaposed in any structure other than the river’s own natural descent from Mount Marcy to the Atlantic” (Hudson River Museum, n.d.). This sonic cartographer was eager to have her map understood as an authentic, if perhaps artistic, representation of her subject.

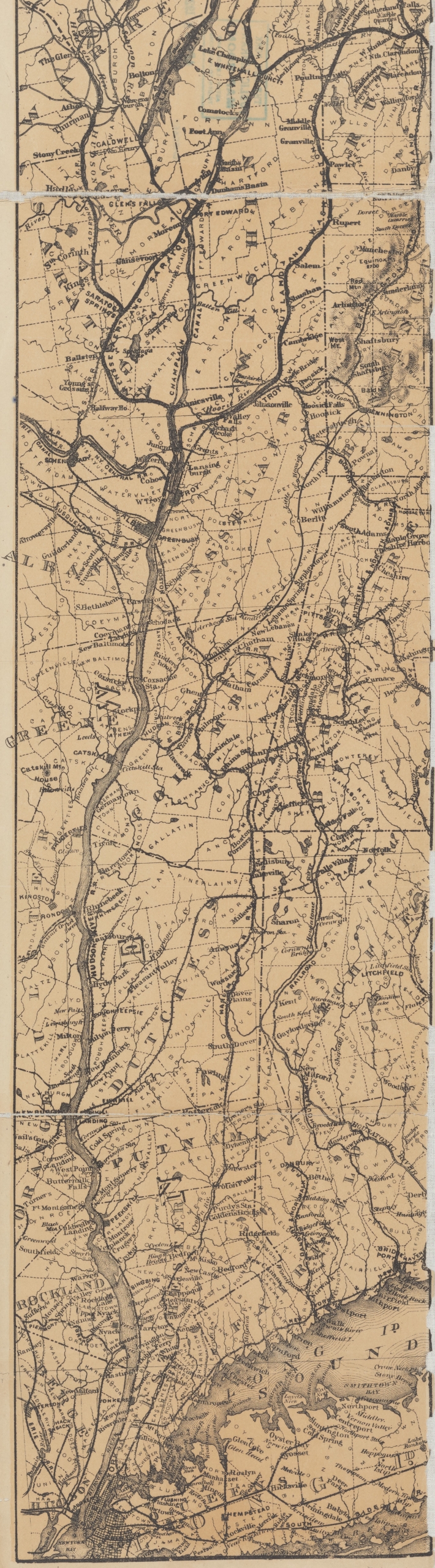

The actual order of recordings, however, was not a straight shot from the northern headwaters to the southern mouth; it wasn’t the way Lockwood had experienced the river herself. Track 1, “Lake Tear of the Clouds, Mt. Marcy” was recorded on June 19, 1982; Track 7 “The Glen” was recorded weeks earlier, May 2, 1982: and Track 11 “Stuyvesant (tugboat and train)” was recorded April 26, 1982. Track 12, “Garrison” was recorded May 9 and October 31, 1982, while Track 13 “Iona Island and Marsh” was recorded on April 17 and September 12. Like many large scholarly projects, sound maps often do not reflect a single, uninterrupted, start-to-finish process despite the over-arching vision directing their creation. Although the final product appears to reflect a continuous experience of the river, it is a deftly arranged series of recorded vignettes . (for orientation purposes using the map that is provided, Mt. Marcy is located approximately 30 miles north of North Creek and 50 miles north-northwest of Lake George). This is in contrast to Sciuchetti’s recording, which captures a continuous journey on the water.[8]

Lockwood carefully selected from her analog recordings to create her map. She liked the “full sound that analog gives” and observed that in contrast to the process of digital recording, the very nature of analog recording matched the uninterrupted motion of water that was so important for her to capture. Although she acknowledged that “water is great to edit; it’s lots of fun,” she, nonetheless, minimally manipulated the individual recordings, mostly to remove equipment sounds and unwanted noises. She then stitched them together with variable cross fades to avoid any artificial (imposed) patterns, ones that didn’t exist in the natural world (Lockwood 2017). She matched and created frequency continuities to mask the discrete beginnings and endings of each of the recordings. The result of her manipulations is a seamless organic-sounding sonic journey that is free of the breaks that recordings taken at locations scattered over hundreds of miles and over a period of eight months would naturally possess. The unique map Lockwood created owes equal debts to the composer’s artistic vision and technological savvy, the museum’s goals for the piece, and the actual river sounds she recorded.

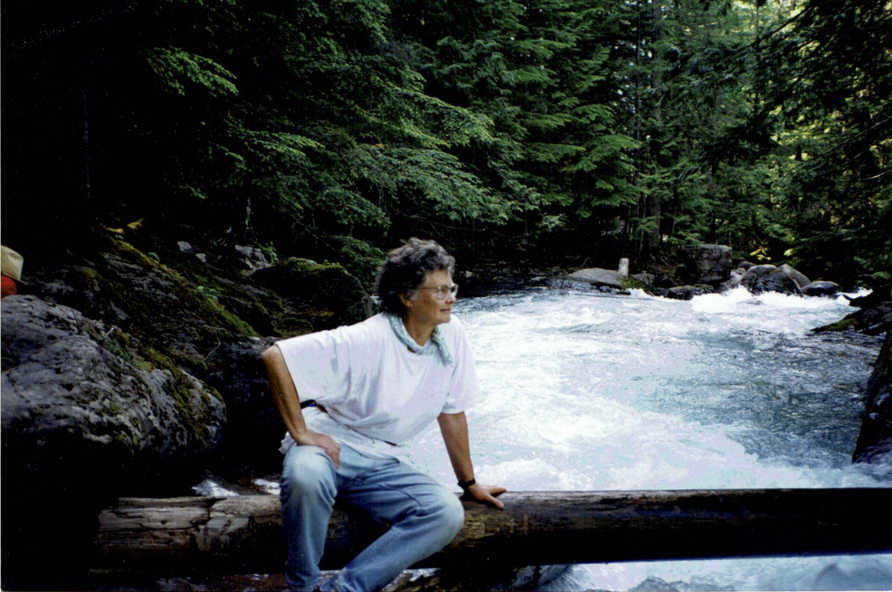

Composer Annea Lockwood sitting beside the river at a site in the Upper Hudson area, possibly at Blue Ledge, during a 1982 recording trip for her piece A Sound Map of the Hudson River. Photo by Sorrel Hays.

The composer explained that throughout the composition process she was curious about the “affects the sounds of water had on people’s physical, mental, and emotional beings.” Lockwood was after a listener’s “sense of floating” (Von Glahn 2017) and sought “the special state of mind and body which the sounds of moving water create when one listens intently to the complex mesh of rhythms and pitches” (Lockwood 1989). Having listened to the CD recording of the work more than a dozen times I can attest to the power of Lockwood’s water sounds to influence an auditor’s state of mind, although “floating” was not my only sensation. There were times when I felt tossed about and even pulled under. Water is not always a soothing presence. Listeners are slowly but surely engulfed by the always present and changing sounds of water: its different densities, speeds, proximities, and depths. For the most part, occasional bird, tugboat, or train sounds only temporarily distract an auditor from the focus of the piece: it’s all about water.

Lockwood captures the variety of sounds residing in the liquid medium: hollow sounds that evoke wooden percussion instruments—box drums (cajónes) and wood blocks—and rushing ones that conjure any number of large, droning wind instruments. I’m taken by the range of resonances that mimic handfuls of glass beads being kneaded, or the crack of a whip, or earthquake-like rumbling roars. The water alternately squeaks and burps, it gurgles, gargles, and explodes. There’s no end to its expressive range. At times the always moving water awakens music hidden in the rocks. I hear it rub against their surfaces and excite them to speak. When tidal waters rush toward and recede from shore, it’s as if the ocean is exhaling and inhaling. It becomes an omnipresent breathing organism with infinite lung capacity.

Beyond the inherent qualities of the watery medium and the celebratory goals of the museum’s commission, the well-known history of the river informed Lockwood’s work in still other ways. The Hudson was not just any waterway; it was among the nation’s first large iconicized rivers thanks to colonial settlement and commerce patterns in the young U.S. The Hudson was of unparalleled strategic importance during the Revolutionary War when a chain strung across its banks purportedly deterred British ships from advancing down the waterway and dividing the colonies. In 1802 President Jefferson formally signed papers founding the West Point Military Academy, about 60 miles north of New York City on the west bank of the Hudson near Poughkeepsie, New York. “The Point” would become the training ground for the nation’s top generals. It was also within the orbit of the Hudson River Valley that Washington Irving set Rip Van Winkle’s story in 1819, and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” the following year.[9] Within the nation’s first four decades then, the river became synonymous with national identity through both its military and literary associations. Well before European settlers arrived, however, the Hudson River basin had been home to indigenous peoples whose name for the river was Mahicantuck. Traces of their presence, including references to sounds associated with their rituals and daily lives, remain in written records of European explorers. Although these past descriptions contribute to the layered history of the soundscapes that Lockwood and Sciuchetti traversed they are not referenced in either person’s sound map.[10] Mark Sciuchetti’s river mapping experience may have started, in part, as a search for an idealized past, a romantic othertime, but what he encountered immediately changed the project. In the next section of this article, Sciuchetti introduces his project and shares excerpts from his first-person account; readers gain another perspective on the river. Von Glahn interleaves observations along the way.

Remapping the Hudson

As a cultural geography doctoral candidate with a master’s degree in musicology, I began my 2017 Hudson River sound map project with different intentions than those that had motivated Lockwood in 1982. I approached the idea of recording the river as a geographer familiar with GIS (Geographic Information System). GIS is a system designed to gather, integrate, and analyze spatial data; it “organizes layers of information into visualizations using maps and 3D scenes.” Taken with Lockwood’s nostalgic reading of the river, and having spoken with the composer about the piece, I arranged to visit and record select locations she had documented; ultimately, they would become part of a GIS map of the Hudson River (Mapping the Soundscape of the Hudson River, 2017). This map includes recordings from all nine sites I visited with my crew in 2017, along with pictures, short narratives, and journal entries of crew members. My sound map would provide a continuous, uninterrupted sensory experience of the everyday on the Hudson River, allowing users to access the soundscape of the river and my experiences through a geospatial multisensory platform, thus creating their own imagined experiences of this place. I began my journey by boat with a crew of three, including Captain David Carter, Gail Carter, and Sandra Edman. As part of my larger dissertation work I sought to explore the connections between place and sound from a perspective on and in the water; it would become another sound map of the Hudson River. With the benefit of time, I have looked back at his journey and Annea Lockwood’s 1982 piece to explore the concept of sound in place, recordists’ experiences, and the importance of context, perspective, and cultural values when examining the soundscapes of a place. In a journal entry from Sunday, August 6, 2017, I clarify my original intentions for the journey (all indented passages and those within quotation marks come from my 2017 Hudson River Sound Map journal and recollections).

During this journey I seek to recreate Annea Lockwood’s 1982 Sound Map of the Hudson River. My goal is to visit some of the same places and try to capture their soundscapes to hear how they have changed in thirty-five years. I will focus intensely on the non-human natural sounds of the various sites.

Sciuchetti orients us to his route, one that heads north from Lockwood’s ending point, where the river meets the ocean:

We begin our journey from Warwick, Rhode Island . . . will travel to Long Island Sound, then through the East River until we reach the mouth of the Hudson and head North. At the marina this morning, the sounds of ducks, fish, and the lightly lapping water catch my attention. I’m distracted from my duties rigging the ship by the nature all round me. I listen intensely as my footsteps in the puddles make different sounds and the wood of the dock squeaks and grinds as I walk across the planks. I tune out everything around me and focus on the non-human natural sounds to learn what I can hear.

Sciuchetti is aware of the challenge he set for himself, but is optimistic nonetheless:

I know that it has been thirty-five years since Lockwood’s composition and that the urban and built environments have changed everything, but I still want to find the romantic, serene, and contemplative places that Lockwood was able to capture; I believe that nostalgic and romantic soundscapes are still present and can be extracted from everything else in the environment.

But just five hours into the journey Sciuchetti was overwhelmed by the deafening “roar of the engine, wind, and other ships.” He consciously redirected his attention to what he could see: “Unlike my original plan to just listen, I found that I took in the sights and beauty of the ocean.” It wasn’t until he could discern the unique sounds of individual buoy bells that he turned his attentions once again to the aural environment.

By Tuesday, August 8th Sciuchetti and the crew had traversed Long Island Sound and the East River and were nearing the mouth of the Hudson. He observed that the long days of riding in the boat for five or six hours at a time had alternately sharpened and dulled his listening. Choosing a different entrance to the river heading north than Lockwood had recorded coming South (the Upper Bay and Battery, rather than Great Kills Beach in Staten Island in the Lower Bay) meant a slightly different soundscape, despite its closeness to Lockwood’s.

It becomes difficult to listen to anything happening around the engine noise, but where there is some loud sound, such as a large wake from another vessel or a coast guard siren, I can focus in on the source of sound penetrating the constant drone of the boat engine.

The Battery, situated near Governor’s Island, Liberty Island, Ellis Island, Brooklyn Heights, Lower Manhattan, and Jersey City is full of boat traffic; the area is condensed producing an echo. At this first location, we backed the boat up against the east side of the river to get out of the way of other boat traffic and water taxies as they darted past us. We were so close to the concrete wall that I could clearly hear the water moving between the boat and the wall. I had expected to hear more of what was going on around us, such as the boats zooming past, but the interaction of the water between the boat and the barrier wall was quite clear. It was interesting to hear the splash of the water in the foreground while planes were going by overhead. We heard a tug boat quickly blast its horn when a small sail boat tried to cross its path.

Sciuchetti replayed Lockwood’s recording of Great Kills Beach (Track 15) to refresh his memory of its sounds “and heard the gentle splashing of waves on the beach, a few bird calls, and distant motor sounds.” He realized not only the difference between it and what he had experienced but also his chagrin: “It was nothing at all like what I had just experienced in the Battery. I was actually disappointed not hearing the non-human natural sounds of the place.” Instead he heard “the sounds of the city and the violent movement of the water.” His experience underscored the importance of one’s location and perspective when capturing audio recordings: “I just kept thinking how different it was to be so close to the water and have the echo of the planes in the cityscape, something I would not have heard if I was sitting on the land or in the city nearby the water.”

In search of Lockwood’s more bucolic experience, Sciuchetti disembarked in the evening and walked in Liberty State Park opposite Ellis Island. He reflected upon the trip so far, still early in the journey:

At this point, I was still interested in capturing a nostalgic and romantic soundscape of the Hudson River . . . I wanted to create a soundscape like Lockwood had created. . . . To my dismay, there were people chattering, jogging, and celebrating at a wedding reception in the park gazebo. I was not able to get away from the sounds of humans and their built environment even in a park. . . . So far . . . I was not able to find those pleasing sounds that Lockwood had found. I was disappointed that the Hudson had changed so much that I could not find what Lockwood had found in 1982. I was still determined, however, and we continued our journey.

On August 9th Sciuchetti and the crew arrived at the municipal dock in Yonkers where he recorded “a nice mix of city and river sounds.” Caribbean music being listened to by the boat captain blended with the constant beeping from vehicles at a nearby construction site; Sciuchetti dropped a hydrophone into the water and listened to the mix filtered through the river. Although he characterized the place as “a soundscape of the city with a few river features heard here and there” he also registered the significant difference between the soundscape at the start of his river journey, “where the city engulfs the soundscape” and here just fifteen miles north of Manhattan where occasional sounds of the natural world came through.

Halfway through the journey Sciuchetti had to confront a set of unwelcome realities: it was impossible for him to separate anthropogenic sounds from the larger soundscape; it was futile to insist upon an exclusively romantic notion of the Hudson; and it was also illogical to assume that there is a single way people should listen. “I needed to allow the entire soundscape into my listening and understand that it is heard differently by different people; it is not just the non-human, pristine, and pleasing soundscape that I had imagined.”

It was only on August 10th as Sciuchetti and his boatmates explored small islands between Ossining and Newburgh, New York, that he “found the natural soundscape [he] had desired.” “Waves lapped against the rock wall and the stern of the boat. There were a few bird calls in the distance.” They came to Iona Island (Lockwood’s Track 13) “a serene place, one of the first that I encountered on the journey, with calming waters and a beautiful view of the marsh. It was as close to the “natural” type of place that Lockwood had captured that I would experience as well on the journey.” At Constitution Island, across from West Point, Sciuchetti heard “recreational water craft . . . jet-skis that created a high-pitched humming.” He also noted that “the depth of the sand bar was deeper than it was down river, creating a lower pitched sound when the water crashed against the rocks.” Rather than be disappointed by the presence of human sounds this time, Sciuchetti made peace with capturing the “soundscape of the everyday . . . the soundscape that people hear in their everyday lives, but often overlook.”

On Friday, August 11th, at Newburgh, New York, about ten miles north of Lockwood’s Track 12 site at Garrison, Sciuchetti recorded the calls of ducks and pigeons that had gathered around an old pier and tour boat, and the flapping of geese as they took off from the water. Lockwood’s six minutes of Garrison sounds in 1982 were similarly filled with the calls and cries of water birds. Having visited Lockwood’s final four sites, time constraints prevented going farther into the more northern locations; the crew reversed direction and headed back down the river where they docked for the night in Jersey City on the west bank of the Upper Bay. Sciuchetti’s ultimate embrace of the everyday soundscape of the River complete with its human inhabitants left its trace in his journal entry: what had bothered him at the start of the journey, the sounds of people at a wedding reception, was now part of “a good day for recording.”

Saturday, August 12th Sciuchetti notes that he records geese in a cove near Jersey City, and on Sunday, August 13th he “attempts to take recordings of fish jumping in the water and of some boats getting ready for a fishing tournament.” His last entry, Monday, August 14th, has the crew heading for Ponaug Marina, “almost home.”

The Hudson River at Garrison, opposite West Point in the lower Hudson area, during a recording trip in 1982 where Lockwood recorded the ducks sequence. Photo by Annea Lockwood.

Hearing the Hudson

From the beginning significant differences characterized the two recordists’ projects: Lockwood’s sounds were gathered over eight months, while Sciuchetti’s were recorded over eight days; Lockwood was a professional composer and expert in using sophisticated recording equipment, Sciuchetti made no claims to either; Lockwood’s piece had, from the outset, an aesthetic purpose guided by the museum’s mission to explain the important historical and artistic roles the river had played. In an early letter to the Associate Director of the museum, Lockwood described her sound mapping project as “a natural complement to exhibitions about the River” (Annea Lockwood to Mr. Coy Ludwig, October 7, 1981, quoted by permission of the composer). Although there was a visual element to Lockwood’s original sound map, she decided never to do that again with subsequent river mapping projects. She had also recorded six people whose lives intersected with the River, which are not part of the CD. Once again, she had always intended the work as an audio experience of “being in the river as it were.”[11]

Sciuchetti’s recordings were made for purely personal purposes partly with a nostalgic impulse, but with the intention of gathering sound data to use for future analyses; he had no commission or outside agent influencing the story he told. When it came to recording the environment, Lockwood remained on the water’s edge and traversed the sites alone on foot while Sciuchetti made his journey from location to location in the water as part of a small crew. He frequently employed a hydrophone, which allowed him to listen and record what happened beneath the water’s surface. Lockwood confined herself to recording sounds above the water using a Nakamichi three-head cassette deck with a 96K sampling rate. If Lockwood kept all traces of herself out of her sound map and focused on the natural world, Sciuchetti’s boat motor is a constant reminder of his presence in the sites he recorded: the Anthropocene is audible, sometimes overwhelmingly so.[12]

In addition to the many particularities of Lockwood’s and Sciuchetti’s purposes and preparations, another distinguishing difference between the two involves the actual provenance of their journeys and the many ways it frames all that ensues. Lockwood’s start at Lake Tear of the Clouds grounds the journey in a soft, gentle, transparent, water-filled sound world. Listeners hear the spaciousness of the environment in the distant bird sounds. Although over the course of the work the pitch spectrum gradually expands, the texture thickens, the complexity of the rhythmic counterpoint increases, and the volume grows louder, it isn’t until almost thirty-five minutes into the work that the unmistakable sounds of human industry become clear: tugboats, trains, the rhythmic squeaks of oarlocks as docked boats rise and fall in their moorings provide the tell-tale signs. But human engagement with the river, however, romantic or benign, is not the part of Lockwood’s sound map that remains with us. Fifty-minutes into the journey water and wildlife take over again. Garrulous shore birds chatter and quack. Sea gulls squawk, scream, and caw. Her piece starts with quiet water and ends with pounding ocean waves. A variety of natural and water sounds frame and populate her map. The natural world is permanent; human beings are transient presences.[13]

Sciuchetti frames the river in reverse: Human industry is the start (and finish) of his circular journey and the sound map that results. Had he continued north all the way to Mt. Marcy and Lake Tear of the Clouds a different story would result, although the lingering sounds of The Battery and lower Hudson would be difficult to erase from one’s aural memory. No one doubts that the river has changed in the thirty-five years that separate the two recordists’ experiences, but rivers change hour to hour, and it is more than temporal distance that changes the way listeners hear and respond to what is recorded. So much of what we understand about anything resides in the frame we use to contain it, the lens through which we first see it. Lockwood’s frame positions the non-human natural world as the origin and goal (a tonic-functioning state of being). Sciuchetti’s experience acknowledges, reluctantly at first, the presence of humans and their sounds as the starting point for his experiences. Boat traffic, weather, tidal regimes, changing currents and water depths mean that one navigates for survival: a different kind of acoustic attentiveness is required (for a discussion of various crew members’ reactions to the river, the tides and currents, tanker traffic, and planes flying overhead, see Sciuchetti 2019, 111). In Sciuchetti’s sound map, one must go away to find the natural world. In Lockwood’s the natural world is where she starts and finishes. To the extent that a listener’s perceptions create a place, the sequentiality of sounds influences understanding and the meanings one attaches to a place.

In a brief 2011 article titled “Ecomusicology between Apocalypse and Nostalgia” published in the Journal of the American Musicological Society, Alexander Rehding discussed “the current interest in ecological topics” and two fundamental approaches to their study: The first he observed is characterized by “a pronounced sense of acute crisis,” which he thought of as the “apocalyptic strain” of scholarship; the second, took “a more romantic line” with “invocations of a sense of nostalgia.” Along with Lawrence Buell, Rehding believed that “commentators have given clear preference to the apocalyptic mode, hailing it as the ‘master metaphor’ of the environmental imagination” (Buell 1995, 285). But he also recognized that music can “appeal to the power of memory, which is one area in which music is known to excel.” He saw the greatest challenge facing ecomusicologists as “bridg[ing] that gap” (Rehding 2011, 412). Rehding’s work may situate the potential extremes of Sciuchetti’s 2017 experience, but it doesn’t fully describe it. Sitting between the abstract notions of apocalyptic and nostalgic is the experience of the everyday. Listening to navigate the river, dealing with quotidian realities, and recognizing one’s practical relationship to the water leaves little time for either romantic fantasies or doomsday dwelling. Can sound maps capture the range of our experiences—our nostalgic yearning for a romanticized past, our recognition of everyday exigencies, and our current concern for the environment—without compromising the truthfulness of their proof?

Both Lockwood and Sciuchetti recorded real places, and in a number of instances the same places. Yet their recordings were framed to suggest quite different readings: Lockwood’s a more romantic, nostalgic reading of the Hudson River that invited listeners to merge with the waters, and Sciuchetti’s a more pragmatic understanding that foregrounded human interactions with the waters. Is either one a distortion? Does either offer a kind of “incontrovertible proof” that Sontag ascribed to photographs? It may be that music best serves our urgent environmental crisis by reminding listeners to pay attention to what is still there and what is being lost. We hardly need sonic reminders of the toll exacted by uncontrolled human enterprise, but the sound of songbirds singing from a distant perch filtered through the intervening atmosphere may speak louder than we think.[14]

Notes

[1] An aerial photograph of the Great Smokey Mountain area would look quite different prior to the 1920s. An exhibit at the Great Smokey Mountain National Park shows the emergence of the lush greenspace we enjoy today from acres of barren land that had been owned by timber companies. The transformation took place over decades starting in 1923. Little beyond the coordinates 35.6118 degrees North latitude, -83.4895 degrees West longitude would have remained the same.

[2] This is not to suggest that sound maps are a recent development. Some of the earliest date back almost a century to the 1920s. For discussions of place recordings please see Caquard et al. 2008; Duffy et. al. 2016; Järviluoma 2002; Krause 2016; Drever 2002.

[3] In 1983 the composer Robert Starer (1924-2001) wrote his five-movement Hudson Valley Suite, another largely romantic reading of the River. For a discussion of Starer and his piece see Von Glahn 2003, 216-225.

[4] Henry David Thoreau had a fuller understanding of the ramifications for the nation of railroad tracks and trains. See The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau, and specifically Walden, the chapter titled “Sounds” for Thoreau’s many references to the rattles, screams, whistles, and shouts he associated with locomotives and railroad cars (Thoreau 1971, 115-122). Leo Marx used the train as the focus of his book The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (1964). It is not coincidence that he starts his study with a chapter titled “Sleepy Hollow, 1844” and an epigraph from Washington Irving’s “Legend.” The railroad was also responsible for accelerating the demise of indigenous peoples in the United States. The impact of the railroad on Native Americans and their culture is a subject deserving its own thorough study; it is beyond the scope of the current one.

[5] All three of Lockwood’s river sound map installations, this one, A Sound Map of the Danube, and A Sound Map of the Housatonic were the results of museum commissions.

[6] It should be noted that the present installation uses Lockwood’s composition as a sonic backdrop to a story focused on the eco-history of the River and its bio-diversity. Without the sound map changing, it has been repurposed.

[7] Lockwood’s statement is quoted in the Museum’s exhibit-installation guide (Hudson River Museum, n.d). The recording from this location is Track 14.

[8] As Sciuchetti explains: “Though the sound maps created in 2017 do not contain the entirety of recordings captured, the fieldwork was conducted on one continuous journey from Warwick, Rhode Island to Newburgh, New York and back. This approach offered an alternate way to explore the Hudson River as part of the everyday with the recordist and listeners as part of the soundscape.”

[9] Sleepy Hollow is the name of a town nestled in the Hudson River Valley in upstate New York. It is in Westchester County, the same county that houses the Hudson River Museum.

[10] According to Henry Hudson, the seventeenth-century Dutch explorer whose name would be attached to the river by colonists, “At their departure out of life, their relations mutually join in weeping, mingled with singing, for a long while. This is all that we could learn of them” (Sciuchetti 2019, 108-109, quoting Asher 1860). In another reference, Carl Carmer’s 1939 study of the Hudson River, the regional historian described what he imagined would be the setting of Haverstraw Bay which includes a reference to the soundscape: “The woods were so full of birds that the noise of their twittering overwhelmed the sounds of the hunters’ approach… And all a man who was also hungry need do to satisfy his appetite was walk into the river shallows and pick up a meal of oysters” (Carmer 1939, 11).

[11] The composer had also originally taken black and white photographs of sites along the river, which were mounted at the museum, and could be viewed as visitors listened. She wanted people to “sense the river as if it were flowing through their own bodies and in that process make a strong connection with the river as a phenomenon” (Lockwood, telephone interview with Mark Sciuchetti, May 18, 2017). The six interviewees included: Captain Dick Roach, pilot of the University New York-Sandy Hook Pilots’ Benevolent Association; Ken Gerhart of Peekskill, who first fished the Upper Hudson in 1947; Robert H. Boyle, author of The Hudson River, A Natural and Unnatural History; Mr. Hunter, a retired farmer of Galusha Island; Jude Kenneth L. Bennet of North Creek; and Chuck Severance of North Creek, a retired Adirondack Forest Ranger.

[12] Anthropocene is a term first popularized by atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen starting around 2000. It refers to the current epoch when human-caused environmental change dominates. Lockwood had recorded recollections of six people associated with the river, which could be listened to in or out of order and separately at the museum if a visitor desired, but they were not part of the 70-minute sound map proper. In this regard a human presence within Lockwood’s Hudson River sound map was optional.

[13] In an interview with Mark Sciuchetti that took place May 18, 2017, the composer acknowledged that if she were to “redo the Hudson, I would . . . place the people, the interviews, within the texture of the river itself, because . . . I came to feel the human beings who work in and on such are a part of the river, the riparian environment just like trees and birds and fish, and aquatic insects, geese, and all the other inhabitants of that ecological system.” Lockwood’s change in attitude reflects changes in the larger culture’s understanding of what ecological systems involve.

[14] I borrow the phrase “intervening atmosphere” from Thoreau. In Chapter 4 “Sounds” he observes, “all sound heard at the greatest possible distance produces one and the same effect, a vibration of the universal lyre, just as the intervening atmosphere makes a distant ridge of earth interesting to our eyes by the azure tint it imparts to it.” See Thoreau 1971, 123.

Bibliography

Asher, G. M. 1860. Henry Hudson the Navigator: The Original Documents in Which his Career is Recorded. Early Encounters in North America. London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society.

Buell, Lawrence. 1995. The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carmer, Carl. 1939. The Hudson. New York: Fordham University Press.

Caquard, S., G. Brauen, B. Wright, et al. 2008. “Designing Sound in Cybercartography: From Structured Cinematic Narratives to Unpredictable Sound/Image Interactions.” International Journal of Geographical Information Science 22: 1219–1245

Drever, John Levack. 2002. “Soundscape Composition: The Convergence of Ethnography and Acousmatic Music.” Organized Sound 7: 21–27.

Duffy, Michelle, Gordon Waitt, and Theresa Harada. 2016. “Making Sense of Sound: Visceral Sonic Mapping as a Research Tool.” Emotion, Space and Society 20: 49–57.

Hudson River Museum. N.d. Exhibit-installation Guide for Annea Lockwood’s A Sound Map of the Hudson River. Trevor Park-on-Hudson, 511 Warburton Avenue, Yonkers, NY 10701.

Järviluoma, Helmi. 2002. “Memory and Acoustic Environments: Five European Villages Revisited.” Sonic Geography: Imagined and Remembered, edited by Ellen Waterman, 21–37. Newcastle, Ontario: Penumbra Press.

Krause, Bernie. 2016. Wild Soundscapes: Discovering the Voice of the Natural World. Wilderness Press (if 2002) or Yale UP (if 2016).

Lockwood, Annea. 1989. A Sound Map of the Hudson River. Lovely Music, Ltd., LCD 2081.

Lockwood, Annea. 2017. Phone conversation with Denise Von Glahn, August 10. Used with permission.

Marx, Leo. 1964. The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. London: Oxford University Press.

Rehding, Alexander. 2011. “Ecomusicology between Apocalypse and Nostalgia.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 64, no. 2 (Summer): 409–414.

Sciuchetti, Mark. 2019. Sound and Place: An Affective Geography of the Hudson River, New York, USA. Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University, Department of Geography.

Sontag, Susan. 1973. On Photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Thoreau, Henry David. 1971. The Writings of Henry David Thoreau, edited by J. Lyndon Shanley. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Von Glahn, Denise. 2003. The Sounds of Place: Music and the American Cultural Landscape. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Von Glahn, Denise. 2017. “Introduction, Appreciation, and Scholarly Pursuits: Part 1.” Journal of the IAWM 23, no. 2: 5–10.